In June 2015, Olaf will be co-teaching ‘Visual Conversations’, a creative photography workshop with Eileen McCarney Muldoon at Maine Media College in Rockport. They will also be running a LightDance workshop in Brooklyn in Sep 2015.

Olaf Willoughby is a photographer, writer and researcher. He is co-founder of The Leica Meet, a Facebook page and website growing at warp speed to over 7,800 members. After conducting many interviews for the Leica Blog, Olaf was recently interviewed there too. Read his interview here.

Here, Olaf shares his thoughts on interviewing and being interviewed.

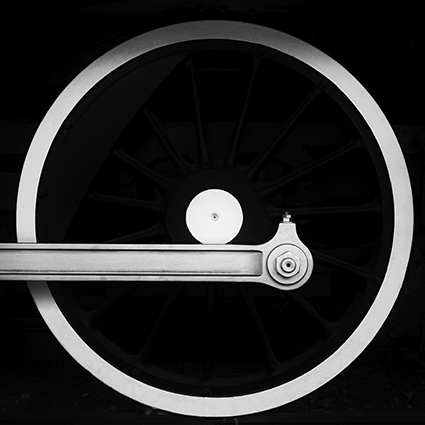

What Makes Photography Tock?

This was the question uppermost in my mind when I started interviewing photographers for The Leica Blog some time ago.

We’ve all worked on ideas which tick like a Swiss watch. They have a magic flow resonating with ourselves and others. But some don’t, they linger on that haunting to-do list and never quite get done. Why?

Photographers are often considered not to be the best judges of their own work, so asking a direct question was unlikely to be productive. I was wondering how to tackle this dilemma in my interviews when, luckily, I stumbled on this quote from Duane Michaels,

‘Photographers look too much. They have to start thinking and feeling and make that the source of their work. Don’t just look for curiosity’. (For more words of great wisdom check Sean Kernan’s interview with Duane Michaels here.)

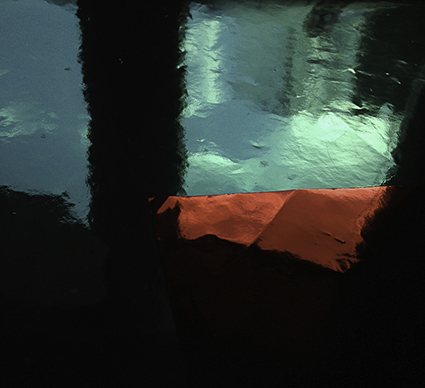

I understood. It identified for me what I love about Michael Ackermann in ‘End Time City’and the shortcomings I see in my own work. Time and again I pressed the ‘thinking & feeling’button in my interviews and it always resulted in a deeper more engaging response.

So when the Leica Blog turned the tables and interviewed me on my ‘Leica in London’Street Photography project (link below) I felt well prepared. Yet initially I fell into the same trap. Rationality ruled. It was only when I let go of the left brain that I could articulate the bigger picture.

Seeing that I had sat on both sides of the interviewing table JP kindly suggested that I might like to share any learnings on his blog.

Working through the process from the questions, to pulling together the images and text and finally telling the story, here are three pointers emerging from my interviews which have helped me to show the work of others in the best light. I hope they work for you too.

Question the questions

Let’s start at the beginning. The fact that I (or anybody else) am asking the questions doesn’t mean they are the right or the best questions for you. If you have thought through your project then you’ll know the one or two critical points you want to get across. Sense check the questions to see if they put the spotlight on these areas. If not, suggest changes or take advantage of the more generic questions to make your point. No apologies if this sounds ‘duh’, obvious. Apart from the big and experienced industry names, most photographers are honoured and excited to be interviewed. Often too excited to pinpoint how they think and feel about their project and whether the questions really search out the soul of their work.

In a similar vein, avoid ‘speed dating’. The tyranny of 140 characters has given rise to questionnaires seeking one word, one phrase answers. ‘What’s the best thing/worst thing about…….?’‘What keeps you up at night? What gets you going in the morning?’.

These work as entertainment. After all, any creative play is good. But they are sound bytes, lacking the conversational element necessary for a good interview. A lot of that dialogue takes place outside the direct questions and answers which are mostly conducted on line. In my interviews I almost always talk with the photographers about their projects beforehand and it is in these conversations that we discuss and sometimes uncover the essence of their work.

A good example is an interview with Italian Leica photographer, Guiseppe di Santis. He had some intriguing shots of the Palio, a horse race, unchanged since 1656 around the Piazza del Campo, Sienna, Italy. At first sight this is already a great sporting moment. Yet it emerges that the real story lies in the ‘contradas’, the neighbourhoods which compete with one another. They have their own flags, costumes, parties. And deeper still is the relationship between Sienna and the horse, which after this dramatic and chaotic race returns to normal life in the community.

Less is more

Moving on to assembling the images and text and to paraphrase Ira Glass, ‘Kill off the poorer stuff so the good can live’. I’m astonished how many times a request for 12 images and 1,000 words for an interview will arrive with 18 or more images and anything from 700 – 1500 words with a request to leave out what doesn’t fit.

Whilst I treasure the trust of these photographers there’s something else going on here. Attachment. It’s all too easy to stay in the comfortable cocoon of an inside-out view of the world. That’s fine when the work is being developed but when it is time to subject it to the sometimes harsh glare of the public, it is better to adopt an outside-in view.

What’s your signal to noise ratio? In our frantic busy world, what is it about your project that will signal the reader to stop and pay attention?

Be aggressive. For the interview to communicate well you’ll need to articulate what makes your work tick. This is where the 140 characters come into their own. Can you communicate the essence of your work in a Tweet? Crazy? Yes. But no-one need see it.

Use those words as a benchmark to review and align both your text and your images. Be ruthless in removing redundancy. This is hard but ask yourself, ‘If there were only space for one image to illustrate my main points, which would I choose?’Repeat twelve times and you’ll have a good idea of which images to submit. Tackle the text in a similar way. ‘If I had to cut every paragraph in half, how would I do it?’Try it, it works.

That’s the disciplined route. But some people, especially photographers tend to think better visually. So another, far looser approach, is to turn the process upside down and start with the images instead of the words.

Using small prints or software like Adobe Bridge, arrange your images side by side so you can easily change the order. Now simply look for the energy. Which images seem naturally to cluster together, almost to rhyme with one another, as though they are part of the same story? Which are the outliers and why?

The beauty of this more freeform method is that the final 12 images seem to come together organically and it is an easier entry point from which to move on to the text.

Start with words, start with images, or bounce around between the two. The aim is to get to the optimum balance between less and more.

A journey of 1,000 words…

Socially we may pride ourselves on being as stable as a rock but if we look back at our photography, we’ll notice how it has shifted over the years. Maybe we were influenced by a new camera or lens, perhaps we went back to film, tried medium or large format or were simply inspired by a workshop teacher. Just as Picasso went through a ‘blue period’, as Georgia O’Keeffe’s color palette changed when she moved to New Mexico, we are all on an artistic journey.

Our images reflect a snapshot of us at a given moment in time. But the creative process also changes us and causes us to evolve in turn. Your project narrative has a beginning and a middle but has probably not yet reached its end.

In an interview it is important to convey a sense of this dynamic. Too many questions stop at, ‘who were your major influences?’. This tends to trigger a dutiful response parading the names of the greats.

A better rider to the question is, ‘…and how did they influence you’. Now we’re getting back to how we each think and feel about our work. And that is what fascinates our readers.

Let me use myself as a brutal example. Major influence? Michael Ackermann. How? By making me feel that much of my work is too literal, failing to capture the looseness and depth of life.

What about mistakes? Projects never run completely smoothly. When did your creative SatNav take you into a cul de sac?

There are always hiccups, which demonstrate our shared humanity and show how we all learn through trial and error. These resonate with readers because they have questions too.

Our personal work should be the product of asking ourselves questions, but so often it isn’t.

Good interviews grab the reader’s attention and then release them to answer their own questions.

Find out more about Olaf Willoughby here.

Read more Alumni Success Stories here.

Post a Comment

Cancel Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

No Comments