Using The Power of Photoshop’s Color Blend Modes

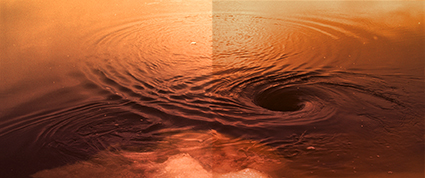

Contrast added – Normal and Luminosity blend modes compared.

Hue adjusted – Normal and Hue blend modes compared.

Hue adjusted – Normal and Color blend modes compared.

Saturation added – Normal and Saturation blend modes compared.

When you adjust color in digital images, several common unintended byproducts arise. Increase or decrease contrast and saturation will rise or fall. Increase or decrease saturation and lightness will change. Make a hue adjustment with Curves (or Levels) by targeting specific channels, and an image will either lighten or darken. Make a hue adjustment with Hue/Saturation, and both saturation and luminosity are likely to shift, sometimes lightening and other times darkening. Correct one problem, and you may create another. Sometimes these byproducts are desirable; usually, they are not. While these changes may be minor, sometimes insignificant, when making subtle adjustments, they can become major when making more dramatic adjustments.

Is there a cure? There are several!

You can make additional adjustments to correct the byproducts of one adjustment. For instance, to compensate for value shifts when making color adjustments by targeting individual channels with Levels or Curves, many return to the Master channel to correct the accompanying shifts in value. To correct saturation shifts when contrast has been increased or decreased, a second adjustment is often made with Hue/Saturation. Some of these moves bring new problems with them, which will, in turn, need additional adjustment. If the problems are minor, usually, the byproducts are accepted. This is appropriate only when the byproducts are desirable and far less than ideal when they are not.

Most of these moves are made in an attempt to stabilize one component of color while another shifts.

Color can be broken down into three essential elements; hue (a spectrum around the color wheel from red through yellow, green, blue, cyan, magenta, and back to red), saturation (a gradient from intense to dull), and luminosity (a gradient from dark to light). These problematic byproducts, typically found in standard methods of color adjustment, arise because only a few exotic color spaces treat the three distinct qualities of color separately. To control only one quality in RGB and CMYK, you typically have to make adjustments to more than one channel. In LAB, luminosity has its own separate channel, and you can make adjustments to it alone, but saturation and hue are still wrapped into two channels, A and B. The color spaces that treat all three elements separately, HSB, HSL, and HSV, are not supported by Photoshop (or Lightroom).

Some adjustment tools allow you to make adjustments to one component of color without affecting the others. Favor them whenever practical. For instance, you can check Preserve Luminosity when using Color Balance to stabilize brightness when making adjustments to hue. This works well when adjustments are made to the midtones. But, when targeting highlights and/or shadows, brightness or contrast may shift. Tools like these build the solution for the problem directly into their interface. But these tools are not always the tools we need to accomplish a given task, nor are they the most precise.

Some tools even produce problems that are not curable. For example, increasing or decreasing value using the Lightness slider with Hue/Saturation will reduce an image’s dynamic range, making white or black gray while darkening or lightening. The best policy is to avoid using these tools altogether. You can do more and do it with greater precision using other tools. (In this specific case, use Curves.)

Wouldn’t it be nice if you could target one specific component of color without affecting the others with any color adjustment tool? When you use Photoshop, you can. You can use the blending mode of adjustment layers to constrain the effects of an adjustment to one or more components of a color. If you are making an adjustment directly to an image without using adjustment layers, you can Fade (Edit: Fade) the problem away immediately after applying the adjustment. Unfortunately, you cannot do this during Raw conversion with either Lightroom or ACR. Many of these side effects are built into the behavior of the sliders, and no additional blend mode feature exists.

You’ll find all of the blend modes in Photoshop’s Layers palette. All layers, including adjustment layers, have a blending mode. A layer can only have one blending mode, but a layer’s blending mode may be changed at any time. The default is Normal. But there are many other modes to choose from. The long list of options you will find under the blending mode pull-down menu, offering seventeen choices in all, may seem overwhelming at first and deter you from using them altogether. While some experimentation with all of the blending modes may prove fruitful, start with the four that are most useful for color adjustment – the four that target specific components of color; Hue, Saturation, Color, and Luminosity.

You can use the adjustment layer blending modes of Hue, Saturation, Color, and Luminosity, to target single color components, regardless of which space you are editing in. The blending mode of an adjustment layer constrains the effects of an adjustment to the component of the color specified in its title. Hue allows an adjustment layer to affect only hue, eliminating shifts in luminosity. Saturation allows an adjustment layer to affect only saturation, eliminating shifts in luminosity. (Use this for most saturation adjustments, for instance, when you use Hue/Saturation.) Color allows an adjustment layer to affect both hue and saturation, eliminating shifts in luminosity. (Use this for most hue adjustments, for instance, when you use a single channel in Curves.) Luminosity allows an adjustment layer to affect only value or brightness, eliminating shifts in saturation. (Use this for most contrast adjustments, for instance, when you use the master channel in Curves. This functions just like adjusting the L channel in LAB without having to make a color mode conversion, possibly forcing you to flatten a file.)

You can specify the blending mode of an adjustment layer when you first create it. Or, you can change the blending mode of an adjustment layer after its creation. Either way, it’s more than likely that you will want to compare the effects of both the alternate blending mode and the Normal blending mode. Sometimes, you may find you like the side effects and don’t want to remove them. In these cases, leave the blend mode on its default Normal. As a rule, with exceptions, I recommend you use the blend mode that targets the element of color you are adjusting.

You cannot reduce a blending mode by a percentage; it’s an all-or-nothing proposition. If, for instance, you want to remove most, but not all, of the additional saturation introduced by a shift, in contrast, you will need to choose a blending mode, either blending mode – Normal or Luminosity and then make an additional Hue/Saturation adjustment. Pick the mode that gets you closest to the result you desire, and then fine-tune the final effect with a subsequent adjustment.

The precision and degree of control over color you can acquire today is nothing short of astonishing. It is responsible for producing a dramatic r/evolution in color photography. We now have near total control of color’s three primary elements – hue, saturation, and luminosity. Add to this nonlinear color adjustment (even color transformation) the ability to affect specific hues without affecting others. Add to this the ability to make adjustments to specific ranges within each of those components, for instance, the saturation of highlights and/or shadows, rather than the component in its entirety. And there are many other possibilities. You can do virtually anything. You need only imagine the possibilities and then find the right tool for the job.

Read more about Color Adjustment here.

Learn more in my digital photography and digital printing workshops.

No Comments