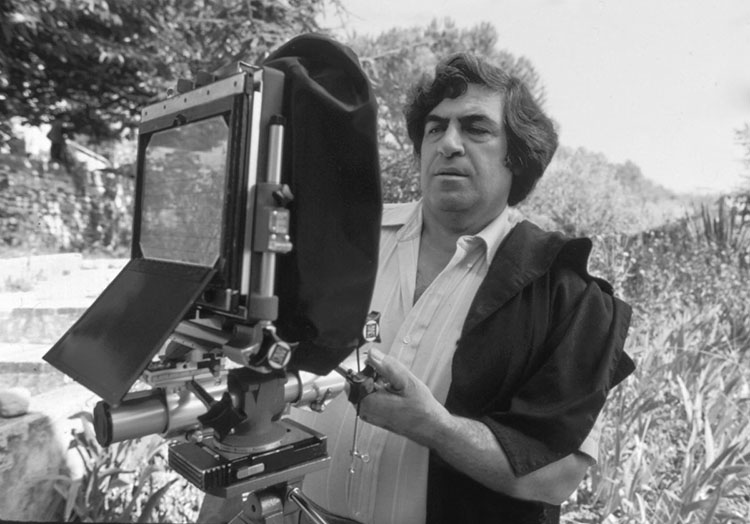

© Ginette Vachon

Paul Caponigro died of congestive heart failure on Sunday, Nov 10.

Born in Boston in 1932, at a young age, Paul Caponigro displayed dual passions for photography and music. He studied at Boston University College of Music in 1950 before deciding to focus on photography. Caponigro remained a dedicated classical pianist, and his music influenced his photography. You can hear him play here.

One of America’s foremost landscape photographers, Caponigro is best known for the spiritual qualities he revealed in natural forms, landscapes, and still lives. His subjects include the megalithic monuments of the British Isles, Scotland, and Ireland; the temples and sacred gardens of Japan; and the woodlands of New England. His photographs are featured in over a dozen monographs, including Sunflower, Landscape, Megaliths, New England Days, and The Wise Silence.

He had his first solo exhibition at the George Eastman House in 1958 and went on to be widely exhibited internationally. Caponigro’s work is in countless collections, including the Museum Of Modern Art, The Smithsonian America Art Museum, and The Getty.

He received two Guggenheim Fellowships and three National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) grants. He consulted with the Polaroid Corporation. In recognition of a career spanning nearly seventy years and a sustained, significant contribution to the art of photography, Caponigro was awarded The Royal Photographic Society’s Centenary Medal and Honorary Fellowship in 2001, was the Honoree for the Achievement in Fine Art presented by the Lucie Awards in 2020, and inducted into the International Photography Hall of Fame in 2024.

First visiting Maine as a boy with his father, later, he spent many summers as one of the first teachers at the Maine Media Workshops, before moving permanently in 1996 to be near his son in Cushing, Maine. Son of George and Mary Caponigro, he is survived by his ex-wife Eleanor, son John Paul, daughter-in-law Arduina, and granddaughter Gwen. In lieu of flowers, the family asks that you consider making a contribution to the Paul Caponigro Scholarship Fund at Maine Media Workshops.

Details about memorials, both in-person and online, will be forthcoming on his son’s website – johnpaulcaponigro.com. Fond memories of Paul are currently collecting on Instagram and Facebook. We invite you to join the chorus celebrating this unique man and his extraordinary art.

–

Below, our photography community shares thoughts, feelings, and stories about Paul.

–

Reid Callanan

“With my very first attempts at making my own landscape images, I was trying to be Paul Caponigro. I soon realized I couldn’t be him. That was a great lesson. As I mature as a photographer, I hold Paul’s photographs on high as my guiding light. I learned that Paul’s photographs unveil and reveal the underlying spirit that connects the natural world. From sunflowers to standing stones to apples and running white deer, his images surround me as reminders of his wise silence.”

_

Sean Kernan

“Paul was an influence on me, not in the sense that my work looked like his (I tried that early on, but soon saw that that place was taken). What I took away from him was, first, that one could conduct one’s self as he did, could aspire to be a seer who chose photography to convey what he saw, and second, that one could do work that seemed simple and was also deeply penetrative at the same time. These were two critical things to learn. I think that a lot of people learned these and similar things from him just by really perceiving his work. I can see echoes everywhere, in your work, for one.”

_

Alan Magee

“Paul’s work and example were an early and indelible influence in my life. He lived and worked above the agitation of fashion and opinion, and in that remove created art that was wise and sophisticated while being always accessible to all.

I remember seeing the page proofs of Paul’s book Megaliths laid out on a table at the Meriden Stinehour Press several decades back. The quiet power of those photographs have never left me, and Paul could find and convey that same gravity and grandeur in a scrap of aluminum foil. Each of his photographs contain lessons for those of us who aspire to make meaningful art. Paul was a masterful visual artist, a poet, and a fine musician—the perfect example of how one might live a fully creative life.”

_

Jennifer Schlessinger

“Making something glow from nothing is a specialty of Paul’s. Paul could find beauty in sometimes simple, modest subject matter, capture it both through the lens and in the meticulous fine printing of the black and white gelatin silver print medium, and produce an end result that elevates its subject to such regal stature. This is what makes Paul a master of our medium.”

_

Andrew Smith

“A photograph is a piece of paper, and Paul Caponigro made the most beautiful pieces of paper. Recalling his prints suggests the comfort in the afterglow of a delicious meal – a satisfaction that the world is in harmony. Using the basic elements of life, the stillness and motion of water, the color and density of air, the warmth of light glowing in the coldest of Irish stones, the quietness of trees and plants pulsing in the darkest shadows of the forest or underneath a rock, the prints emit a universal grounding in these basic elements — birth, growth in all its ages, death and regeneration. All in the lushness of sublime blacks and whites. Whether from his own alchemy or a polaroid, there is a completeness of tone and design–the winking pebble. And on the edges of the shadows there is Paul Caponigro emanating a mischievous delight and expression of joy sprinkling sparkles of light never before seen. My inner eyes revel in the wonder of his vision.”

_

Keith Carter

“Paul was my hero in my formative years. His work was elegant, transcendental, intelligent, and accessible. He introduced me to the possibilities inherent in the human spirit and the cosmic wonders of the ordinary. His work always seemed to me to be thoughtful and the loveliest of celestial gifts.”

_

Kenro Izu

“When I was eager to establish my photography career, on one occasion, I visited an auction house preview and found a portfolio of Stonehenge by Paul Caponigro. The prints were amazingly transparent gelatin silver prints to portray the spiritual stones of several thousands of years old. As well as they were beautiful, I also could hear music from the photographs of the sacred site. Later, I realized the master of photography was also a pianist.

For some time, the quality of Paul’s photography was the benchmark to achieve in my photography. I encountered prints of him, here and there, as if he was reminding me of what a fine photograph is supposed to be. Straight, elegant images with a class. One year, I visited his studio in Maine, and finally met the master in person, and thanked him for continuing to inspire me, though he didn’t know me.”

_

Brenton Hamilton

“My thoughts on the physical work of Paul Caponigro are prismatic. If there is an overwhelming character – it just may be transformation. To have a relationship with his work – to really look at it – you will be drawn within his virtuoso technique – and as unique as that is, that isn’t even the primary impact.

It may be, how Paul, so generously shares his own relationship with the invisible particles of light, the ephemeral, the unexplainable – combining his own energy with seeing and realizing by the act of picture making. I believe this act invokes the possibilities of change. His photographs provide a kind of witness to something unrecognizable, until you have seen his images before you and see what he recognized and wanted to share. That change that I speak of above, and that I have experienced myself in front of his work – Well, that very transformation you might feel, may just be your own heart.”

Arthur Meyerson

“I’ve known John Paul for almost 30 years and had the pleasure of being a house guest at he and Ardie’s home in Maine many, many times. Paul (aka: Babbo, Dad, Papa) was always around and it was like being part of an extended family. I’d always thought JP must have had the most extraordinary childhood, growing up with the likes of the “who’s who” of photography surrounding him… Ansel Adams, Minor While, Eliot Porter…. and the stories that he shared with me about them and his dad only confirmed what I had felt. I remember once asking JP, “So, who was the best printer of that group?” And without skipping a beat (and like a good son) he said, “My Dad!” And I thought, how nice. and asked again, “No really.. who was the best printer?”, “Seriously, Arthur, my Dad was by far and away the best printer of them all.”

Like many, I was always a big fan of Paul’s work and discussed with him how important “Galaxy Apple” was to me and how my wife, Linda, had been mesmerized by “Two Pears”. It was a wonderful conversation hearing him talk about those two images and their backstories. And then, one day the mail came to the studio and there was a carefully wrapped package included. I opened it and inside were two stunning photographs… the apple and the pears with a note, “Arthur, the apple is for you and the pears are for Linda, Love, Paul!” The photographs were the two most beautiful prints I’d ever seen. Add to that, the generous gesture from Paul… and it all brought tears to my eyes. Ever since, those two pictures hang prominently in our home and I walk past them every day and think of the man, his work and his kindness.”

_

David Scheinbaum

“Janet, in her work cataloging Eliot Porter’s prints, discovered a large body of work on the Southwest, all done with an 8 x 10” in the mid-1940s to the 1950s. This work was published, Eliot Porter’s Southwest , 1984. In order to publish the book and an accompanying exhibition, prints had to be made. Eliot, not wanting to convert his darkroom back from dye-transfer to the printing of black and white asked me if I would print this early work. I agreed. At the time I felt I was well trained and experienced in the darkroom and was only slightly intimidated. However, after reviewing a number of Eliot’s negative envelopes, I realized that he pretty much designed a different developer for each image! I had no experience making my own developers and was only peripherally familiar with chemistry. Eliot listed the names of the chemicals used for each negative but cryptic notes regarding the quantities. He printed using his eyes! – not scales nor clocks. I called around to photographers I knew asking for assistance preparing my own formulas. Most photographers were using packaged developers, as I was. When I called Paul explaining my dilemma, he said, “come over tomorrow”.

All the chemicals that Eliot had notated were in bottles on Paul’s darkroom shelves. He printed that morning with me demonstrating how to use each chemical additive and the visual effects and how they affected tonally. This way of printing was an epiphany for me and an approach I spent years sharing with my own students. I don’t think there was another photographer alive who not only had the technical knowledge but the visual sensitivity to approach each image individually and create a developer that reinforces the interpretation of the subject. This approach takes photography from a medium for “recording” to one of “transforming”.”

_

Mark Klett

“I was an 18 year old freshman when I took a workshop with Paul at St Lawrence University. Photography was my hobby, but I knew nothing about fine art photography. After a week with Paul what I had thought was my direction in life had been altered. The last night Paul was in town a few of us went out with him for dinner. We talked about what making photographs meant and I remember Paul saying, “What I’m really trying to do is touch the hemline of God.” My mouth dropped open just as I was about to bite into my hamburger. I wondered, is this really what photography can be about? There was no looking back from that moment.

I had the good fortune to spend an afternoon with Paul developing film during our workshop. We were both developing 4×5 B&W film in open tanks, using metal hangers that held the film immersed in the chemicals. This process had to be done in total darkness, including the necessary agitation of the film by briefly pulling the hangers out of the tank. I was excited the two of us would be standing side by side at the sink because I was trying to learn better technique. Shortly after we began development, he placed his hand on top of mine, “I just want to check how you’re agitating,” he said. I thought, this is great, I’m getting tutored by the master! I was careful to follow his instructions, and not to miss the moment my film was to be agitated. I had it timed to the second.

Then, unexpectedly, when we had only a couple of minutes left in the developer, I heard Paul walk away from the sink. I was puzzled and thought, he’s going to miss his agitation! Suddenly there was a flash of light coming through the blackness from the far corner of the darkroom. I quickly put my hands over the open top of my developer tank trying to prevent the light from reaching the film, and yelled out: WHAT?!! Then I saw the small red glow of a light moving towards me – he had lit a cigarette! Paul said, “Don’t worry, we’re more than 2/3rds through development, it won’t affect the film.” That was my moment of discovery: precision matters when it does, but sometimes it doesn’t, and you need to know the difference.”

_

Bernie Pucker

“Brother Thomas, artist and dear friend wrote, “Risking and dreaming are primary acts of creativity.” Paul’s works seemed to share both the Risk and the Creativity that enabled him to fashion masterworks that generate appreciation and love of the world around us.”

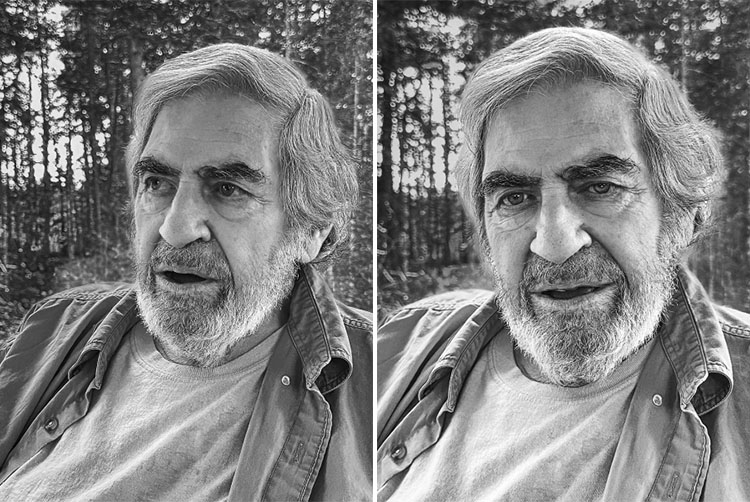

©Alan Ross

Huntington Witherill

“For many years prior to Ansel Adams’ death, Paul would regularly visit the Monterey Peninsula for extended periods of time. During those visits, he would often stay with Ansel and Virginia Adams at their home in the Carmel Highlands. The accommodation was clearly due to a long standing friendship and professional association. However, there was also an ulterior motive. Ansel maintained a good and in-tune piano which Paul was encouraged to play, at will, during those extended visits.

Long story short, after Ansel passed away, in 1984, it became (for reasons of social impropriety) less than ideal for Paul to be taking up residence with Virginia during his lengthy visits to the West Coast. And, while I’m not at all certain who actually informed him that I also maintained a good in-tune piano, at some point in 1985, I received a telephone call from Paul to inquire about whether or not my piano might be available to play while he was in town.

Needless to say, the opportunity to begin hosting Paul each time he would make the occasional pilgrimage to the West Coast became one of the greatest opportunities of my lifetime. Although the initial attraction had nothing to do with me (and everything to do with my piano) the friendship that developed and ensued was, and remains, immensely rewarding.”

_

Arno Rafael Minkkinen

Paul Caponigro is “a lost treasure to be found forever and ever by new generations.” This afternoon with the visit of our five-year-old granddaughter, Griffin, I put that sentiment to work immediately. We sat on a couch beside the fireplace near the Living Room library, to which Paul’s Masterworks book now belongs. After counting the number of white running deer on the cover we happened to turn to the S-like fragment of the Blue Ridge Parkway in Virginia. “From which direction would you say a car might come first?” I asked. “And how long would we have to wait?” Griffin’s reply came with a zigzag of her hand: “It’s just going to be like that.” It was a first lesson in recognizing the stunning stillness of a photograph, as only Paul Caponigro does it. Even with deer in motion.

_

Elizabeth Opalenik

“In those early years, I missed Paul’s connection to Connecticut until the day I walked into his photographs that had left such an impression on me the first time I saw them. I crossed a river and knew, absolutely knew, I had just walked into a Paul Caponigro photograph. How could that be….I was just on a small bridge over a little river? Craig had introduced me to Paul’s work in 1979 at my first MPW workshop and I was struck by the essence of what was within the images, something certainly beyond an image of a river or apple…something beyond my photographic knowledge at that time. How simple, yet poignant were the images…everyday things imbued with a spirituality that left a deep impression, obviously, for there I was, in the middle of Paul’s photograph. Unbeknownst to me, I was at the house he once rented, now owned by my friend. It wasn’t just the river in front of me, but the emotional poetry that continued to resonate through the power of his photography…that visual voice for stories left behind, now a whisper from the Maestro to be pondered again.”

_

Tim Whelan

“I was working in Paul’s studio in Santa Fe waiting for him to come down from the house. He was not in a good mood having stayed up late the night before trying to get a print. He explained that I was not to interrupt him for any reason. I was hearing a lot of swearing, banging around and incantations most of the day. The print was clearly not behaving. A call came in from a photo dealer in Atlanta who urgently and insistently needed to talk to Paul. I told her ok, but warned her it would not go well for either of us. Paul emerged glaring and grabbed the phone. After a few emphatic no’s he slammed the phone, admonished me and returned to the print.

At the end of that long day. He came out and asked me who the hell Elton John was. I explained he was a piano player who dressed a little differently than he did and made it clear to him that he should go to Atlanta. He explained that he had more important things to do. I never interrupted him in the darkroom again.”

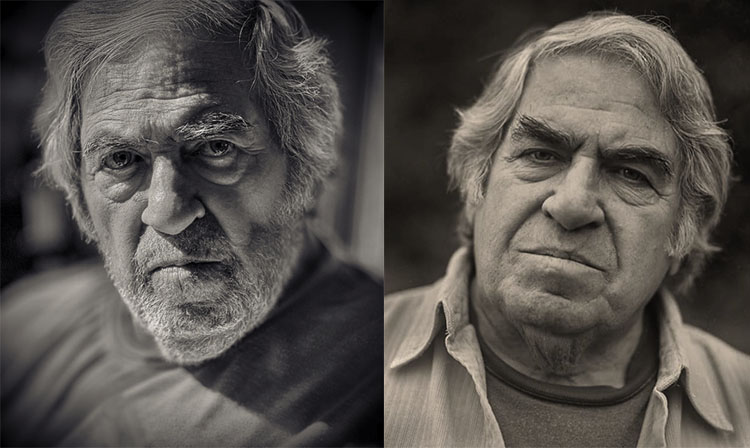

© Skip Klein, November 9, 2024

Skip Klein

“When I married my wife 35 years ago, part of the dowry was a poster by a man I did not

know at the time. Judy had purchased the poster of the rooftop of a Buddhist temple for her dorm room at Penn. Forty years later, we are still in possession of the poster. We love the image, the prophetic title, and the poster has come to mean a great deal to us. On my first visit to Kyoto in 2018, I trekked up Mt. Hiei to find that temple and stand where Paul must have stood with his Deardorf to make that impactful image. Today, a large silver gelatin print of the warrior monk temple from the always inspiring Pucker Gallery hangs on the wall in our bedroom.

I first met Paul in Cushing well over a decade ago. We stood in his studio and he suggested that I “just listen…and stop asking so many damn questions.” He gave me his book also named The Wise Silence with a personal inscription, “See No Evil, Speak No Evil, Hear No Evil—Silence.” He must have enjoyed at least some of the questions as he invited me to come back, and thus began years of provocative, generally but not always pleasant interactions, and a great deal of learning about so many things ranging from the angels that visited Paul to Gurdjieff to Minor White to piano lessons to selenium toning, and to the importance of just taking deep breaths and remaining silent.

While those of you who know me may not believe it, I did learn to be silent in Paul’s presence and soak in the wisdom his years of experience, deep thought, and true seeing could provide. If not a better photographer, I know I am a better person for having spent more time in the wise silence of Paul.

Saturday November 9th, was my last visit with Paul and he was more talkative than usual, filling me up with more words of wisdom and even encouraging me to ask questions. He agreed to let me make an iPhone image of the handsome beard he had grown since my last visit. When I returned on Sunday November 10th with two of his favorites from Maine Media, Rachel Coleman and Kari Wehrs, all we found was silence: a hard, cold silence. But after some tears and sleepless nights, there is now Paul’s wise silence coming forth from that final silence. I did learn from him that while his body may not be here, his energy would transform and his spirit would be here with us along with his spiritual images. Above all, I do know that his memory, the wisdom he shared, and the spiritual images he leaves behind, will all be a blessing for us all.”

© Robert Minden

Michael Kenna

“It seems like only yesterday, but it was eight years ago when you and I last met in New York. On that occasion, I had the good fortune to attend one of Paul’s lectures. It was a startling talk in that, even after the thousands of hours he has spent teaching and in the public eye, he delivered it as if chatting with a close friend. There was no hype, artifice, salesmanship, ego inflation, or bullshit (with apologies for any hurt sensitivities). Rather, it was refreshing, inspirational, illuminating, and, yes, charming, which seems very typical of the man and his photographs.

I didn’t know Paul very well, but in my humble opinion, based on the occasions I met him in person, he seemed genuinely comfortable in his own skin, living his life on his terms. I have a feeling that he would always call a spade exactly what it was. I think that in his photographs, Paul simply and consistently recognized and acknowledged the extraordinary miracle in what most of us regard as ordinary subject matter. Being a superb master craftsman, he then skillfully produced stunningly gorgeous prints to share with the rest of us, mere mortals. Nil Satis Nice Optimum. Nothing but the best is good enough. Farewell, dear Paul. You will be missed more than you know.“

_

William Clift

“There has been more than enough expressed regarding the art of Paul’s photography. Alongside that, for many of us, was his art of helping.

He would look at a print and point to a little section in the corner perhaps and say “That is where there is life.” Nothing ever about composition or techniques, only his entering into our inner world via an image.

We met in 1959, when I was 15 and already enthusiastically at home in my bedroom darkroom. A little later I met him in his apartment in Arlington, Massachusetts, and showed him a bunch of prints, images of my much younger brothers and sisters. He looked through them – no mention of anything specific.

“You have a spark. Photography can be a means to contact that.” That’s all. And it was enough for me. Later–maybe it was after I had quit the pointless, for me, college experience–another visit, this time to his basement apartment on Newbury Street in Boston. I brought a single 8×10 print from a 4×5 negative of the bark of a tree. He put it up on an easel and looked quietly at it for 10 or 15 minutes. No words. Just looking, one of many examples of that kind of attention.

In 1962 he introduced me to the ideas of Gurdjieff as conveyed by Willem Nyland. These two poles–photography, an artistic effort, and the specific application of Gurdjieffian ideas of spiritual development in ordinary life –formed a direction for me.

Again, the photographic endeavor was never once described, only indirectly encouraged.

That, along with a very definite atmosphere of his own piano music and Willem Nyland’s, as improvisation, and Gurdjieff’s own sacred music, created a world of emotional possibilities.

Paul and I knew each other for 65 years. Learning something about silver printing, developing very gradually my craft and emotional intuition, sometimes in the dark, photographing forever without formula or method. Sometimes alive, often not. Doing, not talking.

Caponigro knew how to help – indirectly, from behind, not from in front.”

_

Tillman Crane

“Dear Paul,

Thank you for being you. You were an inspiration, a teacher, and a mentor. Most of all, thank you for being a friend.

The Wise Silence was in my library long before I ever hoped to meet you. First and foremost, your work was an inspiration to me. I first saw one of your prints in 1981. I was in awe. It glowed like no other print I had ever seen.

“Master the Zone System, then forget it. Craft is essential to art, but craft alone is not art.” We spent hours discussing this balance of art and craft over coffee when your studio/darkroom was next to mine in the School House in Rockport. One day, I was running the wet line for you in the darkroom while printing Running White Deer. You distracted me while the prints were in the developer, and they went 5 seconds too long. The next day, when we came to look at the prints, you could tell which two had had 5 seconds too much development time. I knew which ones they were because of where I placed them in the print washer and on the drying racks. But you found them. You understood with your head and your heart which two were so slightly too heavy. They felt wrong. I had to tear them up. “Keep the best trash the rest.”

Practice. Practice. Practice. Photography was the primary focus in your life. Being an artist meant working every day. Practicing, making images, making prints, sharpening your eye, you called it playing scales. You created still-life images when you couldn’t be out in the landscape—always playing with light and shadow, arranging and rearranging. I loved visiting your house to see what you had collected and how it was arranged. If I was lucky, you would share new images with me. They were often unmatted, clearly in the work print stage. Once you showed me prints of aluminum foil. You had balled it up, folded it done all sorts of things to it. Hidden in the stack was one print that stopped me in my tracks.

Everything about it was stunning. You pressed the aluminum foil onto your face and then photographed it. The image was a death mask but a mask filled with light and complexity. It was best seen upside down, as you saw it on your ground glass.

You were always honest with me. It’s a very rare trait. You had no problems telling me what you liked about my work and what you didn’t. You told me what I needed to hear not what I wanted to hear. Sometimes bluntly but always with genuine honesty. You demanded my best and accepted nothing less. Mentors show up when they feel called. I did not know I needed a brutally honest curmudgeon to show me how to be an artist. But I did.

These last few years, we have been able to laugh or cry about our experiences in China. What an interesting couple of years that was. I was disappointed that our exhibitions weren’t hung at the same time, but what an experience for both of us.

I see your prints every day. They never cease to astound. Your glow still shines.

Thank you, my friend and mentor.”

John Sexton

“Anne and I were deeply saddened to learn of Paul Caponigro’s passing on November 10, 2024, just weeks shy of his 92nd birthday. The news instantly created a void in msy being. Paul Caponigro is a name that resonates with nearly all who love the art of photography, as he stands among the true legends of the medium. His extraordinary career spanned nearly seven decades, leaving an indelible mark on the field. Many of you, no doubt, can visualize a number of Paul’s iconic images as you reflect on his remarkable legacy.

Anne and I extend our love and heartfelt thoughts to Paul’s son, John Paul, his wife, Ardie, their son, Sol, and the entire Caponigro family, along with all of Paul’s close friends. Paul’s charming and engaging personality touched many lives, and he was loved by many.

Much has been written about Paul’s long and illustrious career, but I hope to offer a glimpse into the friend who helped guide my journey in photography over the past five decades. Paul’s influence extended beyond his words; I learned and drew inspiration from both what he said and the quiet wisdom in what he left unsaid. His breathtaking images and stunning prints continually motivate me to pursue the passion I feel so fortunate to embrace today.

I first met Paul in April 1974, a little over 50 years ago, during the Ansel Adams Gallery’s Easter workshop in Yosemite. It was only the second photography workshop I had ever attended. Alongside Paul, the workshop’s instructors included Wynn Bullock, Henry Holmes Smith, Norman Locks, Roger Minick, and Joan Murray.

My interactions with Paul during that workshop were both significant and lasting. I had the privilege of observing him in the field as he worked with his 5×7 Deardorff camera and to see him work in the darkroom. However, the most profound and memorable moments came during a print critique session. Each participant shared their portfolio, and Paul approached the task with a quiet, methodical focus, carefully studying every print.

Although I had experienced critique sessions the previous June at an Ansel Adams workshop with several instructors, including Ansel himself, Paul’s approach stood out. While he addressed the technical aspects of photography, offering both praise and constructive suggestions, his feedback went far beyond the technical. Paul asked thoughtful questions about feelings, ideas, and emotions, inviting deeper reflection, rather than making proclamations.

As a 20-year-old relatively new to photography, I found the questions posed during the critique challenging. In the moment, any answers I could come up with felt inadequate. As the session progressed, I came to realize that Paul’s questions weren’t meant to be resolved immediately. Instead, they were designed to provoke thoughts, to be reflected upon, and to guide each photographer’s growth over time. While I received a limited amount of praise–along with considerable constructive criticism–the questions highlighted areas in both my life and my photography that needed deeper consideration. The critique didn’t leave me disappointed, but it did leave me unsettled, with much to think about.

After the intense critique session, I decided to retreat to one of my favorite spots in Yosemite—Fern Spring, to ruminate and digest what Paul had said and how I might try to better understand the wisdom he shared with all of us that afternoon. As I sat alone next to the diminutive Fern Spring, I felt rejuvenated by the landscape that I loved, and clarity began to slowly filter into my young mind. As time passed, I decided to make a photograph. It seemed the best way to begin to search for answers to the thought provoking questions Paul had posed.

I feel incredibly fortunate to have maintained a friendship with Paul for over five decades. The lessons I learned from him and the other instructors at the 1974 Easter workshop shaped my growth as a photographer. So, when a few months later, I learned Paul would be teaching at the Newport School of Photography in Newport Beach, California—just a short distance from my parents’ home—I jumped at the chance to attend. That workshop, too, was a transformative experience.

One of the exercises we all participated in was making simple prints of solid black, white, and various shades of gray in the group darkroom, under Paul’s guidance. For this exercise, the enlarger wasn’t loaded with any negatives, which initially felt like an unusual approach. However, the purpose became clear the next day when the prints had dried. Paul instructed us to cut out squares and rectangles of varying gray tones, from deep black to bright white, and encouraged us to play with these tones as he spoke about the magic and beauty of silver prints. It was fascinating to see how a light gray could appear as bright white when placed on a black background, or how two adjacent gray tones could create a sense of resonance. This thoughtful and meditative exercise revealed the subtle complexities of tonal relationships. Over the years, I have borrowed this exercise and incorporated it into my own teaching.

Paul’s remarkable talents as both a photographer and a pianist have been widely celebrated. His passion for classical music and his extraordinary skill at the piano were evident to all who had the privilege of hearing him play. I had the pleasure to hear Paul play his Bösendorfer piano at his home in Cushing, Maine as well as on several occasions when he visited Ansel and Virginia’s home. Paul’s musical expression was as distinctive as his photographic voice, and his ability to orchestrate light in his prints was truly amazing.

On the first day of the workshop, Paul showed us to his Portfolio One, a breathtaking collection of 12 prints. The price of the portfolio, which had been published in 1962, was $1,200. During our lunch break, one of the workshop participants came up with a unique idea: if 12 of us contributed $100 each, we could collectively purchase the portfolio—if Paul agreed. This way, each of us would own a Paul Caponigro print for just $100, significantly less than his usual prices at the time. After lunch, the organizer of this idea approached Paul with the proposal. Paul responded warmly, saying, “That sounds like a fine idea, but what will you do with the beautifully printed title page, the list of photographs, and the portfolio case?” The plan was that there would be a lottery-style drawing for the selection of the prints, and then we would have another drawing for the additional components. Paul whole-heartedly agreed to the somewhat unusual proposal.

I was eager to participate but faced a problem—I only had $50. The only other photographic print I had ever purchased was a beautiful Ansel Adams Special Edition of Yosemite, which, thanks to the workshop discount the previous June, had cost me just $10. That evening, I shared my predicament with my close friend and photography professor, David Drake, after his class. I explained the day’s events and the opportunity to own a Caponigro print. To my surprise and immense gratitude, David offered to loan me the $50 I needed. I gladly accepted his generous offer. While I don’t specifically remember repaying him, I’m certain I must have, as we remained close friends for many years until his passing in 2007.

Amazingly, by sheer good fortune I ended up with my first choice of image, Frosted Window No. Two, Ipswich, Massachusetts. The print has been framed, and on the wall, for more than five decades, and still provides me with a calm joy every time I see it.

I visited Paul twice at his home in Santa Fe, New Mexico, during the time we were both teaching as faculty members at a workshop held there. Later, when I began teaching at the Maine Photographic Workshops, Paul was “in residence” at the Workshops. A few years after that, he relocated to Maine full-time. Every summer, while I taught at MPW, I would visit Paul, and we often shared a meal together. We also enjoyed a number of meals during his regular visits to the Monterey Peninsula.

Here’s a note I received from Paul, dated April 1st, 1999:

Hi John and Anne –

I understand we are sharing the walls of the Alinder Gallery this month.

Sorry not to be at the opening and in fact miss very much not being at the Pacific Coast this year. And then I heard that you will not be coming to Maine this year–how’s a guy supposed to squeeze a good meal and a fine bottle of wine out of you if we can’t get together!

At times Paul could be a bit of a curmudgeon, but what I can see in my mind’s eye is his warm smile, and I will always remember his wonderful sense of humor. For those unfamiliar with him, oftentimes his dry, yet witty delivery often flew under the radar until the moment people realized he was playfully pulling their leg. Over the years, he would occasionally include a cartoon with a letter entirely unrelated to our ongoing communications, simply to share a laugh. Paul loved to laugh, he cherished life, and, to borrow a phrase from the late, great photographer Ruth Bernhard, he is now “flying with the angels.” His legacy will soar for many generations and his photographs will continue to inspire, pose questions, resonate, and become indelible memories in countless people for years and years.

I believe every meaningful photograph is, in some way, a self-portrait of the photographer who created it. Paul’s extraordinary body of work forms a mosaic that offers a glimpse into the heart and soul of an exceptional and singular human being.

Rest in peace, Paul.”

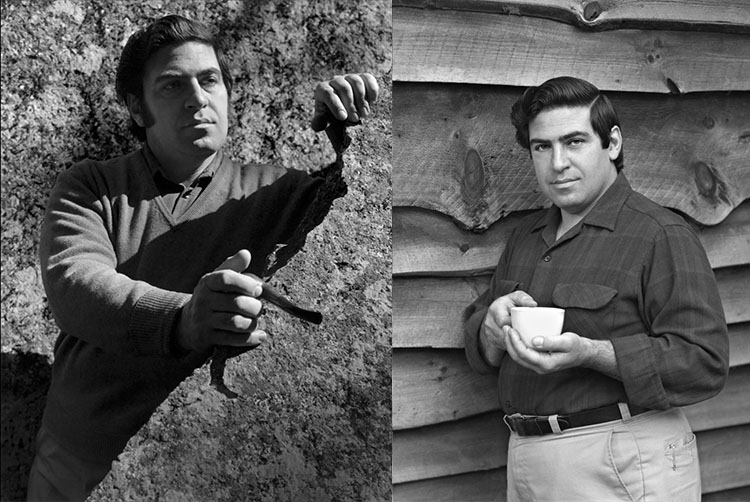

©Jeff Schewe + Jeff Kay

Jeff Schewe

There’s an old adage “Don’t ever meet your heroes”. I suppose that’s because many “heroes” will disappoint you in real life. That’s not the case with Paul Caponigro. I first met Paul at Huntington Witherill’s house somewhere near Carmel, CA almost 25 years ago. What I remember about that first meeting was the calmness and serenity of the person and the whit and whimsical sense of humor.

The opportunity to meet Paul was arranged by his son, John Paul-who has since become a close friend. The reason I was excited to meet Paul was he was one of my all time favorite “Photo Heroes”, people whose work has had a great influence on me. I particularly appreciated the quiet serenity Paul’s photographs imbued in the world he saw and showed us. Somehow, he created a spiritual magic in a photographic print.

The second time I met Paul was with my daughter, Erica, who was immediately charmed by this gruff old man. But Paul and Erica had something other than photography in common, music. Erica had played the cello and Paul played the piano. They talked music not photography.

The last time I met Paul was a few weeks before he passed. Paul was nice enough to look through some photographic prints I had brought while JP was in his kitchen making pancakes. Paul looked at a few prints and asked if I had more. He seemed to be in his natural element, looking at a photograph. I will always cherish the time he spent with me and the kind words he shared. I’m really grateful I got to meet this particular hero…

His loss is a tremendous loss to his family, his friends and the entire photographic community.

–

Peter Fetterman

“I have spent most of the last 40 years deeply involved in the world of photography not as a photographer but as a collector and a gallery owner. I take very bad photographs of my children and now my grandchildren. I have never worked in a dark room and the technical aspects of the medium are beyond my comprehension But what I think I do know is how to judge an image and how to judge a person.

I am constantly dealing with living photographers and people who are interested. In collecting in the medium. Maybe I have encountered tens of thousands of photographers over all these years. Very few of them are truly exceptional. Paul was one of the few who was .not only exceptional as an artist but as a human being.

The work was just so special in its power and beauty. That now seems self evident .What perhaps was not so obvious was that the work was Paul and Paul was the work. They were one and the same

I was given the deep gift of knowing him and being in his presence on many occasions in many different cities.

One encounter stands out in particular. I had found a wealthy patron for him and encouraged the patron to host a special evening for him and to invite friends who might also be interested. In supporting a great artist. I suppose I was trying to reinvent a Medici salon in the rich hills of Bel Air in Los Angeles. I brought many samples of his work with us . Paul politely spoke about each of his images with great personal insight and dignity. He held the audience in the palms of his hands. He was not giving a performance. He was just being his authentic self. Out of the corner of my eye I noticed a piano in the grand room. I asked Paul gently would he be willing to play something for the assembled crowd ? He graciously agreed and played a Chopin nocturne. The audience was literally in tears as I was too. The combination of great images and great music was impossible to not be deeply moved. It was an evening that no one present, including myself, would ever forget.

Paul handled the balancing act of being an artist and “making a living” with such grace and integrity like no one else I have ever dealt with. To a man possessed of such an incredible talent he was truly humble. He started his career when you could not give photos away and ended his career when people were willing to buy these same images. It really didn’t make an iota of difference to him. He was constant and passionate about his craft. regardless. People like Paul are a rare and endangered species. He was a constant inspiration to me and I know to many others. I think of him as a giant oak tree in a forest standing above all the other trees but spreading his branches out to touch us all. His light will never fade.”

_

Joyce Tenneson

“Although Paul was over a decade older than me, we always acted like we were old friends who knew a lot of funny stories about each other! When I was in my 20s, I used to spend a lot of time in the south of France teaching and having exhibits of my work. Those were times when we stayed in the same small hotel where most of the people who were invited guests of the international photo festival were all as well. There were also parties and private chalets and trips to gorgeous private wine cellars and collectors vineyards … but what I remember most about our days weeks in the south of France were all the women that Paul enchanted with his fun stories and his obvious joy at being around a lot of gorgeous and talented women! In July, the weather was hot and there was no air conditioning so we were often in the garden and many of the women started taking their shirts off and going topless to get their suntans. The waiters would be passing glasses of wine and champagne, and we were all enjoying ourselves immensely in this fun environment! In the evenings, we’d all be invited out to dinners and the party continued. Other Summers, we were invited to teach at the Maine Photographic Workshops, and there was always a great group of photographers, taking photos and showing off their new work! We had evening slideshows from the visiting photographers and talked until the wee hours! Paul was always the photographer most people wanted to and learn from… the women in particular love to hear paul play classical music on his piano – and fell in love with his sensitive photos that he enjoyed showing us all. In the past few years when I have been with Paul, we just talk and laugh about our past. I will miss that easy joy and camaraderie that I so treasured!”

_

David H. Lyman

“Paul and I go back aways.

Paul taught a printmaking master class that first summer of The Workshops in 1973. Eleanor and their young son John Paul, only 7 at the time, joined him. He returned the next two summers, then took a long break from teaching.

It was around this time, mid-70s, that Eleanor and JP moved to the New Mexico desert; for what reason I don’t know, but Paul soon followed.

In 1981, Kate and I stayed with Paul for a few days that winter following an SPE conference in Colorado Springs. His adobe home, on a hillside outside Santa Fe, was small and neat, with a sweeping view of the valley to the west. Eleanor and JP lived on the far side of that valley, providing him with just enough proximity. You’d think he’d found the ideal lifestyle, but the elevation eventually got to him, as did the summer heat. This wealthy artist enclave in New Mexico is over 7000 feet high.

Paul would make his way back to Maine nearly every summer, rent a cottage somewhere near Rockport, one that had a piano, and hang out at The Workshops in Rockport. You could fine him most mornings holding court on one of the benches in front of Union Hall, and on sunny afternoons, he was to be found reclining on the ledges that slipped down into the sea on the east side of the harbor. They became known as Caponigro’s Rocks.

There were the occasional evening soirées at Paul’s cottage where he’d play the piano for students, staff, and fellow artists. He could always be counted on to show up at the Thursday faculty lawn parties I hosted. He was always a welcome addition and would linger long into the evening to chat with George Tice about chemistry and papers, discuss craft with Cole Weston or John Sexton, and explore some aspect of photographic history with Ernst Haas.

Every year, I would ask him to lead a summer workshop. He declined. I ask him if he’d like an “official” title, seeing as he was a fixture in our community.

“How about Artist-in-Residence?” I ask. “Would that suit?”

“Too much responsibility. Just call me Artist-in-Residue.” We did.

One summer in the late 70s, Kate and her 6-year-old daughter, Aileen, and I were having breakfast at the Corner Shop, across the street from Union Hall. Paul walks in and sits down with us. After he departed, Aileen asked if that was Mr. Crack-an-Ego. An appropriate monicker, I thought. Any fledgling photographer bold enough to show Paul their silver prints of bark, roots, and peeling paint was apt to suffer instant “ego death.”

Paul led only a few workshops for us over the years, but his presence was constant. Every summer, he’d show up in Rockport after having spent the winters on the West Coast. The elevation in Santa Fe did not suit him, and neither did the winters in Maine. It was one of those winters, late 80s. I found him house sitting in a splendid estate overlooking the sea near Big Sur, south of Carmel. The view was not the draw; it was the piano, he told me. I spent a week with him, cooking, shopping, and listening. He evidentially needed an audience and would entertain me with a sonata or two following dinner, then an hour or two of philosophy. One evening, I asked to be excused to fetch my journal. I wanted to capture some of this wisdom he was dolling out. “Sit down and listen,” he admonished. “I know you want to capture this and use it in your writing. You can’t write about this or speak of it until you have lived this for at least ten years. Otherwise, you become just another disciple.” He was right, of course. In this teacher-student, master-protege game we play, requires time for the student to make those lessons their own.

It was at one of these evenings, overlooking the dark sea, white caps illuminated in the light of a half moon, when Paul began telling me a story of something that had recently happened to him there on the California coast.

Out walking one day, he’d stumbled off a cliff near the house and rolled down the bank, ending up unconscious in a patch of poison ivy. Someone found him, and he was rushed to the hospital. There in the IC Unit, he came close to death.

“I was at that door, the one that opened into blinding light,” he told me, as I now recall. “I was ready, even eager to enter. Then a figure appeared in the opening and began to shut the door, saying, ‘It’s not your time. You still have work to do.’ And the door closed.” A month later, I received a small, printed booklet of his story. I have around here somewhere, I’m sure. I’ll look. If you have one of the few printed copies, I’d love to read that story again.

Especially now, since he has finally passed through that door. He used the gift of those additional 35 years well. He will be missed, of course, but he leaves behind some much of himself; it’s as if he’s just down the road a piece.”

_

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.