Personal Projects

Defining a project is one of the single best ways to develop your body of work. When you define a project you focus, set goals, set quotas, set timelines, create a useful structure for your images, collect accompanying materials, and polish the presentation of your efforts so that they will be well received.

Focusing your efforts into a project will help you produce a useful product. A project gives your work a definite, presentable structure. A finished project makes work more useful and accessible. Once your project is done, your work will have a significantly greater likelihood of seeing the light of day. Who knows, public acclaim may follow. Come what may, your satisfaction is guaranteed.

Create a mission and set goals.

Define the purpose of your project and what you’d like to achieve through it. Many times, people adopt the mission and goals of others without first checking if those goals are personally beneficial. Some have professional aspirations, others don’t. Your goals will help you determine projects and timelines that are appropriate for you. The few moments (or hours) you spend clarifying why you’re doing what you’re doing and what you’d like to see come of it will save you hours, months, even years by ensuring that you’re going in the right direction – a direction of your own choosing. When you take control of your personal projects, you also take control of your life.

Make a plan to achieve your goals.

A plan will help make your project a reality. A simple action plan is all you need to get started. Action plans define the steps that are required to achieve completion. Action plans should be clear and practical. Action plans should be flexible; odds are, things will not go exactly according to plan and you’ll need to modify your plan to accommodate surprises, both pleasant and unpleasant. Reality happens. Grace happens too. Having defined what you need to accomplish, your unconscious will go to work on the task, generating many ideas. You’ll find yourself ready to make the most of unexpected opportunities as they arise.

Set a timeline.

A timeline can be used to combat procrastination and/or distraction and encourage you to produce work. Set realistic timelines. Unrealistic timelines simply produce frustration.

Identify where and when you’ll need and who will help you.

While many artists define and produce projects themselves, some artists engage a curator, gallery director, publisher, editor, agent, writer, or designer to help them realize a project, in part or in whole. Finding the right collaborator(s) can improve any project. Above all, seek feedback. Seek feedback from people with diverse perspectives whose opinions you value and trust. One thing you can always use, that you can never provide for yourself, is an outside perspective. People with different perspectives may identify ways to improve, expand, or extend the reach of your project. Remember, feedback is food for thought, not gospel. In the end, all final decisions are your decisions; it’s your project.

Stay focused and follow through.

You can work on multiple projects at a time. Be careful that you don’t get scattered. Starting projects is easy. Finishing them is hard. Make sure you’re working on the best project. List all your possible projects and identify the ones that are most important and the ones that are easiest to finish. If you’re lucky enough that the same project fits both criteria, focus all of your efforts there. Otherwise, you’ll have to strike a balance between what’s practical and what’s most important to you. Only you can decide this and the balance is likely to shift as time passes and circumstances develop. Look for a common theme among projects. Often your projects will be related. Focus your efforts in related areas. It’s very likely those areas have greater relevance for you than others. Your work will be perceived as stronger and more cohesive if your projects relate to one another, implying evolution.

What’s your project?

A project is a wonderful thing. It gives direction. It brings clarity. It increases productivity. It produces tangible results. It brings personal growth. It presents your work in the very best light. You and your work deserve this. Pick your projects well. They define not only how other people see you but also what you become. You are what you do. Take the first step today; make a commitment to create a personal project. (Write something right now – put your words somewhere where you’ll constantly be reminded of them and can continue refining them!)

Plan to plan.

Many people refuse to plan, especially in creative fields where discovery is desired. They say, “Failing to plan is planning to fail.” Everyone needs a plan. Often, when you start a project, knowing you need to learn more as you go forward, you feel like you don’t have enough of the pieces to make a plan or you don’t have all of the pieces to make a complete plan. My recommendation is to start with a rough plan and continue to refine it as you go.

Stay flexible.

The best plans aren’t written in stone. The best plans remain flexible. Flexible plans allow you to make course corrections along the way as you learn more about your subject, your medium, yourself, and your audience. Expect to update your plan. I find that, if I don’t update my plan during the development of a project, this a clear indicator that I haven’t found the insight(s) necessary to complete it. I expect to be changed, for the better, by the projects I engage in. I expect to grow.

It helps to have a mission.

You have so many options before you, and so many more will soon present themselves to you, that you’ll find it challenging to choose which project(s) to move forward on or which path(s) to choose during project development. Defining a mission for your creative efforts in general will help ensure that you stay on track.

Be prepared to be surprised.

You don’t have to know all the answers before you begin to work. You just have to know the most important questions. Creating is a matter of solving mysteries, of finding answers. You don’t have to solve a mystery completely; you just have to find a few answers that you can stand by. If you’re lucky, you’ll find new questions and new mysteries along the way.

Find your groove. Find your message.

Doing things consciously, repeatedly, and consistently brings mastery. Repeat your successes … and find meaningful variations on them. When you do this you give your work a theme and style, which communicate a message. When does a groove become a rut? Don’t worry about the rut too soon, most people don’t stick with one thing long enough to find a groove. They go off road, traveling anywhere and everywhere, by any and all means, and ultimately don’t end up anywhere in particular, much less a place to return to, a place they can call their own.

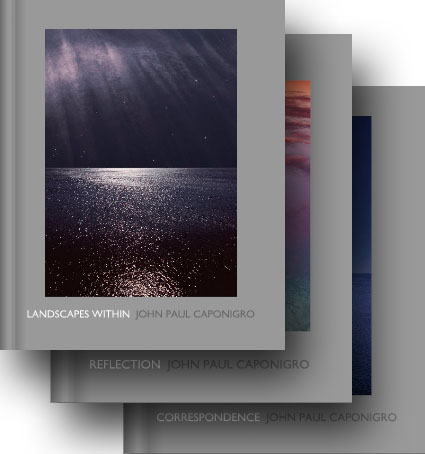

Past projects lead to new projects.

Often the seeds of future work lie in present work. Themes that were unclear or latent, at the beginning of a personal project, once developed, lead to new lines of inquiry and more work. A creative life is never truly over. The best creative lives evolve; growing deeper, more complex and more sophisticated.

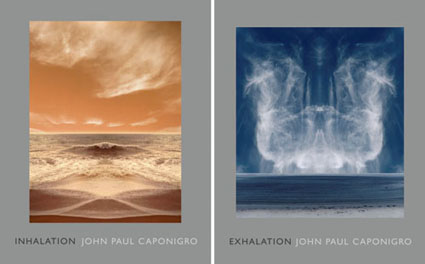

Prepare to make your work effective.

Even the best images will go unnoticed if they’re not presented and promoted properly. If you’ve spent a significant amount of time and resources to develop a personal project, you own it to yourself to see it presented well. This may be as simple as presenting your images well to yourself or as complex as promoting a publication and or exhibit, physically and/or virtually.

Make visible touchstones to guide your progress.

If you’ve got a personal project you want to complete, make a visible touchstone and keep it in one or more places where you can see it frequently. By doing this, you’ll be directing your conscious mind to focus on it and suggesting to your unconscious mind that this is a matter of importance – both will start to work on the challenge, even when you’re unaware of it. You will literally be sleeping on it. Many of the best ideas come during this period of gestation and incubation.

Projects take time.

It’s unlikely that you’ll be able to finish a project in a day. Projects can take weeks, months, or even years to complete. Some projects are ongoing and never end, producing many milestones along the way (publications, exhibitions, commissions, etc). Some projects lie dormant for a period of time and then suddenly come to life again. Projects have a life of their own. Personal projects require commitment, but the depth of your commitment will be reflected in both you and your work and in the achievements you make with it.

Read more and see specific examples on scottkelby.com.

Read more in my free creativity ebooks.

Discover and develop your personal projects in my digital photography workshops.