How To Identify Actions With Verbs

This article is part of a series …

2. Discover Qualities With Adjectives And Adverbs.

3. Identify Actions With Verbs.

Develop the habit of making lists and you’ll dramatically sharpen your powers of observation and retention. (We’re 72% more likely to remember and act on what we write down.)

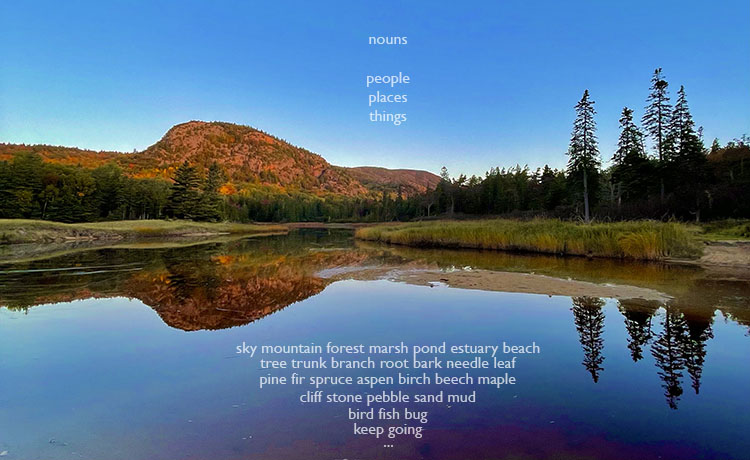

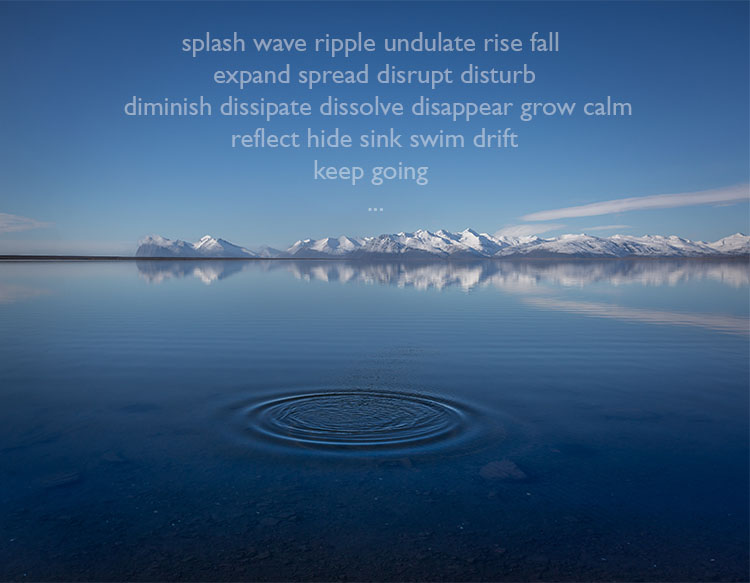

After you identify the things (nouns) in your environment, identify what’s going on or the actions taking place (verbs).

For photographs to transcend becoming simplistic visual inventories they need to tell a story. That means something has to happen in them. So you need verbs. However, actions come in many flavors. They can be dramatic or quiet, fast or slow, active (peak action) or passive (a frozen gesture). Often we don’t recognize all the things that are happening around us simultaneously and making a list of them all will help you be more observant.

Don’t let this practice get in the way of capturing peak action. If you see something significant about to happen get ready ahead of time. Not surprisingly, if you’ve been making your lists, you’ll be more prepared and practiced and so more likely to notice it before (not after) it happens.

Usually, there’s so much going on around us that we miss things. Periodically putting your camera down and just looking carefully will help you see more. And, if you become more mindful of the events around you and their interconnections, you’ll make more insightful images.

Is it enough to simply make mental lists? It’s a start, so do it. But if you always take this shortcut, you’ll be missing out on some of the long-term gains of developing this habit – wider, deeper, more memorable, with the ability to identify patterns either in your environment or in your ways of relating to subjects and your medium. Again, action speaks volumes and pays dividends.

Find more ways to boost your creativity using words.

Learn more creative techniques in my workshops.