The Calligraphy & Color Of Trees – 6 New Studies

I’ve been chasing the calligraphy of trees.

What stories they tell.

Then I lifted up the colors of the leaves and gave them to the sky.

I’ve been chasing the calligraphy of trees.

What stories they tell.

Then I lifted up the colors of the leaves and gave them to the sky.

Kenneth Nolan

Eliot Porter

Alan Bray

Wolf Kahn

Alex Katz

Lois Dodd

Dahlov Ipcar

Jamie Wyeth

Andrew Wyeth

Louise Nevelson

Eric Hopkins

Fairfield Porter

Alan Magee

Robert Indiana

Peter Ralston

Paul Caponigro

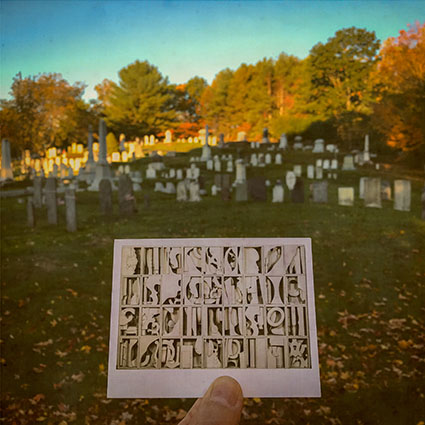

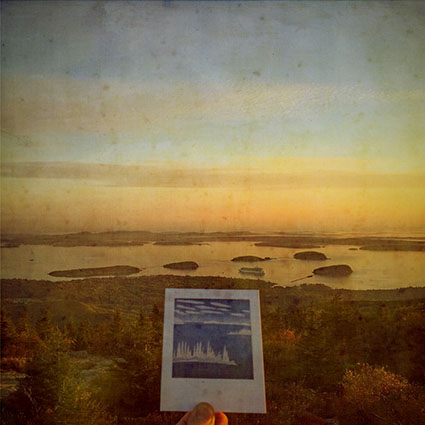

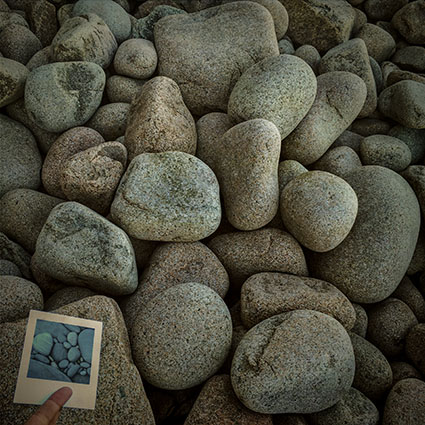

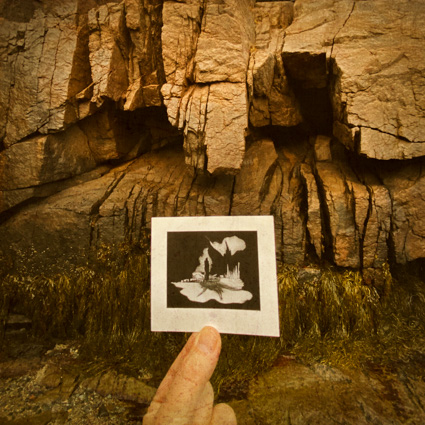

For years I’ve been photographing postcards of artworks made by master artists in Maine. Each artist has their own strong connection to the same place and their own way of seeing it. Do they find what’s iconic about Maine or do they make it iconic? Photographing images of their works in locations that feel relevant to their works provides a unique way of looking into Maine, what they make of it, and what I make of it.

View more studies here.

Find out about my Maine Fall Foliage photography workshop.

Two of my recent studies (experiments made and processed entirely on an iPhone) combine historical photographs with contemporary exposures.

Exposures for Antarctica Now & Then were made at Whaler’s Bay, Antarctica on the active volcano Deception Island.

Exposures for Greenland Now & Then were made in the East Greenland village of Ittoqqortoormiit.

I’ve been wondering if there was any connection between these explorations and the work that was foremost on my mind during these voyages.

At first glance we seem to make many unrelated images, but often it’s just a matter of finding the connections. Sometimes we find the connections between what we were thinking and feeling while we are having the experience; sometimes we find the connections long after; sometimes we never find them. At the very least, doing one thing provides a rejuvenating break from the other. There’s usually more going on than we are consciously aware of.

What connections have I found? I was looking into the spirit of the land in these locations and these two experiences provided stark contrasts to that sensibility. People concerned with the spirit of a place wouldn’t kill whales in the way they were slaughtered in Antarctica; thankfully this activity has stopped. That bygone members of Greenland’s indigenous population had a stronger sense of the spirt of the place and practices for interacting with it than the quickly westernizing current members do was made evident in the art they left behind. Was my experience limited by my cultural inheritance and current circumstances? Could I, a westerner living today, also participate in more sacred ways of relating to the earth? I think so.

The finished images I produced on these trips, for my series Revelation, are evidence of this.

1

2

I’ve spent the better part of my life exploring symmetry, especially bilateral symmetry. (You’ll find a chapter on Symmetry in my book Adobe Photoshop Master Class.)

When I make symmetrical images I pay careful attention to three things: one, the dividing line that defines the symmetry, the seam whether visible or not and any repetitive patterns surrounding it; two; rotation along the dividing line; three; what’s included in the areas that surround the dividing line, especially when contours are present.

I’ve explored creating out of phase symmetries, where two or more images of the same moving subjects shot at different times are used.

In this selection of symmetries, I explore creating varied but related symmetries from different angles of the same subject (icebergs) – 1-2, 3-6, 7-9.

View the finished works of art here.

See more in my exhibit New Work 2016.

View inkblot studies here.

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

1

Klecksography is the art of making images with inkblots. Spots of ink are dropped onto a piece of paper, which is then folded while still wet to create mirrored patterns. Symmetry most powerfully stimulates, apophenia, the human tendency to see meaningful patterns in random data.

The history of using inkblots as tools for stimulating imagination can be traced back as far as the late 1400’s. Both Leonardo da Vinci and Boticelli used them.

Interest in this practice grew wider in the late 1800’s when physician and poet Justinus Kerner collected his studies in a book Klesksographien, which was published posthumously. Kerner, also a mystic poet, felt that such drawings not only brought him in closer contact with deeper aspects of his nature but also drew him closer to the spirit of nature.

Around the same time, a similar game was described in the book Gobolinks or Shadow-Pictures For Young And Old (Stuart and Paine), which explained how to make inkblot monsters and use them as prompts for imaginative writing.

Some years later, psychologist Hermann Rorschach made the most enduring contribution to this practice. As a child he enjoyed klecksography so much that his friends nicknamed him “Klecks” (inkblot). While studying Freud’s work on dream symbolism (under the tutelage of Eugen Bleuler, who also taught Carl Jung), Rorschach’s interest in klecksography was rekindled. He published his book Psychodiagnotik (1921) and invented his now famous Rorschach Test, seeing it as a potent tool to stimulate visual free association, which would in turn uncover unconscious tendencies and desires, much like Freud used verbal free association. (From hundreds, Rorschach selected ten inkblots, designed to be as ambiguous and “conflicted” as possible.) Since then, many other psychologists have refined the Rorschach Test and used it as a tool for studying the subconscious. In the 1960’s it was the most widely used projective test.

I’ve found exploring inkblot symmetries extremely rewarding. The perceptual transformation that occurs when making them and the visual skills this practice kindles has influenced my art in many ways.

Here’s a sampling of my most recent digital inkblot studies.

What do you see in them?

View more of my inkblots here.

View some of my finished works of art that were influenced by klecksography here.

See more in my exhibit New Work 2016.

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

During my recent Fall Foliage / Acadia Maine Workshop we explored many of the highlights of Acadia National Park; Cadillac Mountain, Sand Beach, Thunder Hole, Monument Beach, Sieur de Monts, Wonderland and more … including an overnight stay on the Schoodic Peninsula at The Schoodic Institute).

We had great color, great weather, and great light. Great weather means a little bit of everything; clear sunny days with direct light, overcast days with soft indirect light, fog and mist, even a little rain (perfectly timed, mostly over night). It was an almost perfect study of weather, the many lights it brings, and the many moods it creates. We oscillated between two powerfully magnetic poles, the colorful forests and dramatic seacoast.

People ask me if it’s challenging to make images in a place I’ve visited so many times. I tell them its like reconnecting with an old friend; the relationship gets deeper. What’s most challenging is that many of the subjects don’t complement and even challenge key aspects of my life’s work, so I take a lighter more personal approach and rather than rushing to finished professional results I engage in deep play, asking many questions and trying many things, both new and old, to find more clarity in my creative life.

Here are a few of the sketches I produced on sight with my iPhone.

You can enjoy many more images on Google+.

Find out about my next Fall Foliage / Acadia Maine Workshop here.

Email info@johnpaulcaponigro.com to receive advance notice on our next Acadia Maine Fall Foliage Workshop.

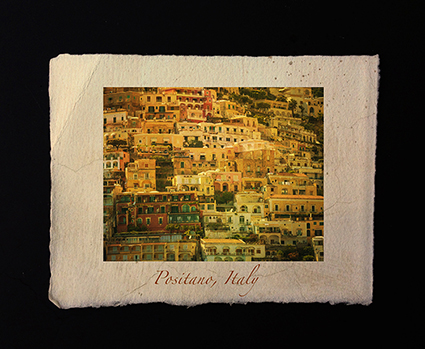

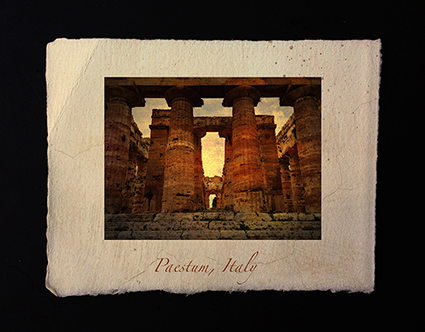

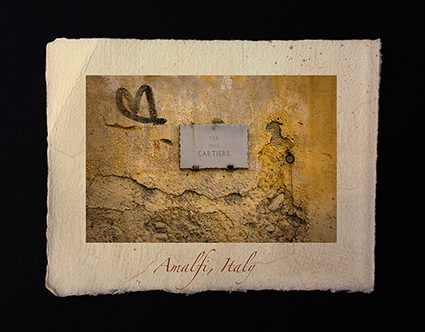

We made many memories during our recent boutique (limited to 6) workshop in Amalfi, Italy. The coastal towns of Amalfi and Positano (famous for making world class ceramics, paper and limoncello), the international concert series in Ravello, the sunny Isle of Capri, the Greek ruins of Paestum, and the ruins of Pompeii once buried by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius are a few of the places we visited. Of course, the food and wine was fantastic!

You can enjoy my images of from our recent adventure on Google+. They’re an assortment of spontaneous sketches, rather than a collection of fully finished pieces that develop a cohesive theme. They’re not likely to become a body of work, but a few of them will influence other bodies of work.

Find out more about our recent Amalfi workshop here.

Email info@johnpaulcaponigro.com to receive advance notice on our next Amalfi workshop.

(Drawn on the iPad with Adobe Ideas.)

Here’s a collection of recent landscape sketches.

Drawing does many things for me. Drawing helps me find, refine, and expand ideas. Because of drawing I’m never at a loss for visual ideas – and consequently I become more discriminating about the ones I devote significant time to. Drawing helps me identify essential structures in existing images. After I draw them, (no longer hung up on the details) I understand them better and can better apply what I’ve learned to other images. Drawing helps sensitize me to fundamental compositional patterns. After I draw them, I recognize them more quickly.

For so many reasons drawing is an immense pleasure – and that’s why I keep doing it.

View more sketches from this series here.

See more drawings here.

Most images can be compared to a stage. There’s an environment, a central character (often with a secondary character), an action performed, a prop (or two or three or four, maybe more), and light. Props are thought of as so secondary that we often overlook them and their contributions to great dramas. At a minimum, props make an environment richer and more interesting. Sometimes props do more, providing a catalyst for action or a stimulus for interaction.

Try using props in your images to stimulate many creative ideas.

When it comes to props, you’ve got options. Props can be single or multiple, repeated or varied, found or purchased either on site or offsite, old or new, manufactured, handmade, or natural … just keep going. The possibilities are seemingly limitless. Almost anything can be a prop.

Finding the limits of what makes a prop may be one of the most insightful things you’ll learn during your explorations.

There are some fine lines to explore when using props.

Props can make or break images. The right prop animates an image making it stronger. The wrong prop confuses and disrupts an image’s integrity. Appropriate really isn’t an appropriate word to use when selecting a prop. Sometimes an inappropriate or absurd addition is what adds meaningful ambiguity, tension, or complexity. Useful is a better word to use. When choosing a prop, ask yourself. “Does it contribute and reinforce or does it distract and detract from a statement?”

The story and character props bring with them can add interest and energy to almost any image. Props can turn ordinary images into extraordinary ones. Props can also clutter or overload picture-perfect pictures. There is much to be gained by exploring the differences between placing props in already strong compositions and deliberately weakening the graphic impact of a composition, making it perfectly imperfect, to emphasize the storied quality a prop contributes.

Using props raises a lot of questions. In fact, it may be the questions props raise that make them so full of potential and possibilities.

Is an object a prop if you find it rather than select it? Props are usually deliberately chosen rather than incidentally found (except in existential dramas or French films) because rather than dumbly filling space they comment, whether directly or obliquely, on the place, person, or events at hand. Props are relevant.

Is it a prop if you don’t move it? There’s an interesting distinction to be drawn between photographing found objects that haven’t been moved and those that have. Whether the distance is long or short, if you transport an object to a new location it becomes a prop.

Does repetition of the same prop change its function or status as a prop? If a repeated prop is not placed in context carefully it can become the central subject. Used strategically repeated props can provide continuity between two or more images. Firearms are not the only smoking guns found in mysteries.

Is it a prop if it’s the central subject? An object photographed with a minimal background is a study. A found set of objects is a still life, though many still lifes are selected, moved, and constructed.

At what point does an object become a prop? It’s useful to remember that, rather than stealing the show, props prop something else up. Props are supporting actors in a larger drama. Props are used for accent, counterpoint, and interaction but they are rarely the central focus, at least not the sole focus. Admittedly, the line drawn between a prop (a secondary element) and a subject (a primary element) can be very fine, at times almost indistinguishable.

There may be no definitive conclusions to these questions, save the images you make.

What is undeniable is that each move you make has consequences,

You’ll learn a lot by looking at how other people use props in their images. Here are a few examples of great uses of props in photography.

Joyce Tenneson often asks the subjects she makes portraits of to hold objects that contribute something elusively poetic to the picture.

Horst Wackerbarth has made a career of transporting a red couch around the world and photographing it in all manner of locations.

Sean Duggan’s series Artifacts Of An Uncertain Origin, places man-made objects in an unlikely way into natural scenes as if by magic.

Albert Lamorisse’s movie The Red Balloon, which was later adapted as a book of stills, takes its title from a prop that becomes more than a prop or a central character in the drama.

Keep looking for other good examples and you’ll find there’s more to learn every day.

With just a little more thought, you can go even further. Physicist Richard Feynman championed the thought experiment. Just imagine what you can do with props.

If William Shakespeare is right and “all the world’s a stage … “ then how you accessorize your images, and perhaps even your life, with props, will speak volumes.

Find more resources on Creativity here.

Learn more in my digital photography workshops.

Here’s a selection of my iPhone experiments with props.

I love to draw. I began drawing before I could speak. I’ve never stopped. It took me decades to learn to draw the way I wanted to. I spend less time drawing than I used to, now I rarely draw to produce finished results, but hardly a day goes by when I don’t draw, to record or refine ideas.

Drawing is a way to understanding. There’s a difference between knowing things mechanically (with a camera) in 1/125th of a second and knowing it manually (with a pencil, pen, or brush) over the space of hours or even days. Both ways can inform one another.

People often ask me, “Do you draw before, during, or after I photograph?” I respond, “Yes.” There are different benefits to drawing at every stage in the process of creation.

I sometimes draw before arriving at a location to structure my visual explorations. I sometimes draw while on-site, to record ideas that cannot be photographed. I sometimes draw after visiting a location, from unfinished photographs made there, to identify the many ways they can be combined with other photographs. I sometimes draw on finished photographs to identify patterns of thinking and ways to develop them further.

There are many reasons to draw and many ways of drawing.

I take the definition of photo-graph literally – light-drawing. For me, photography is one more way to draw.