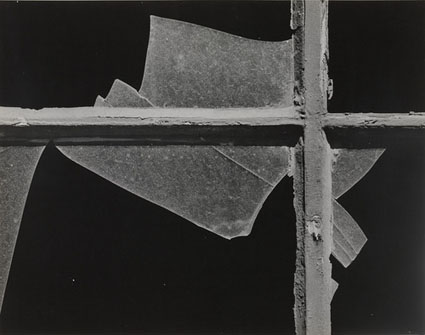

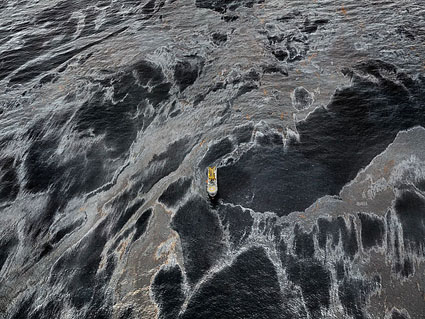

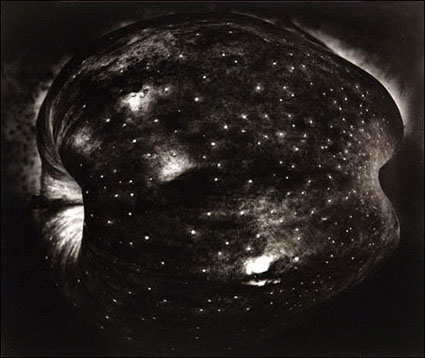

Masterworks In My Collection – Paul Caponigro – Apple, New York City, 1964

While this image is officially titled Apple, New York City, 1964, it’s often referred to in my father’s studio as ‘The Galaxy Apple’. Countless people’s first impression of this image is that they’re looking at a galaxy. Even after you see the apple, the impression of a galaxy persists.

This is one of the photographs that got me fascinated by photography. I love that a literal transcription can also describe something more than itself. The power of metaphor is more powerfully expressed in this photograph than in any other I can think of. What’s more, the way the metaphor unites both the terrestrial and the celestial – the macrocosm and the microcosm are seen as one. (I don’t think it’s an accident that my father’s first retrospective was titled The Wise Silence, a line borrowed from Ralph Waldo Emerson.)

The printing of this image reinforces the metaphor. It’s dark. It is so dark, in fact, that in some places, you can’t visually separate the contour of the apple from the dark background. Dad found the solution while printing the image; one of the proofs came out darker than anticipated. Other printers might have held all the details there were to hold in this negative. Unexpectedly and wisely, Dad didn’t. I have always appreciated my father’s consummate ability to transcend his technique and follow the call of his intuition. Rather than offering expected results, he consistently delivers unexpected solutions, not for the sake of novelty or surprise, but because he was called to serve a more powerful inner poetry.

(There’s a lot to be learned from looking at originals, which is why we look at masterworks from my collection in all of my digital printing workshops.)

Find my comments on other Masterworks In My Collection here.

Learn more in my digital printing workshops.