Equivalence

The idea of equivalence in photography is richly rooted in a time when photography was beginning to discover its own nature and continues to be a powerful force for discovering our own nature, which is greater than we think.

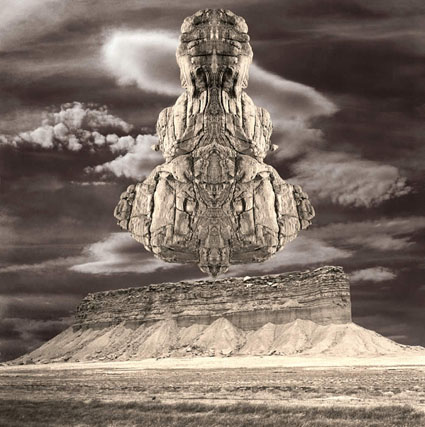

Alfred Stieglitz first used the term equivalent as a title for a series of photographs of clouds, whose aspirations were more musical than representational, and to describe a particular kind of activity in art and its result, “My photographs are ever born of an inner need – an Experience of Spirit … I have a vision of life, and I try to find equivalents for it sometimes in the form of photographs.” In stating that his photographs have power “not due to subject matter” he suggested that photography, capable of but not limited to abstraction, can move beyond transcription without abandoning verisimilitude. The visible can be used to reveal the invisible; the external can be used to reveal the internal.

Extending what Stieglitz started, Minor White stated, “When a photograph is a mirror of the man, and the man is a mirror of the world, then Spirit might take over.” Equivalence embraces and elevates the debate over whether photographs are windows (onto the world) or mirrors (into the soul) and whether they are taken (through distant observation, objective to varying degrees) or made (through immediate interaction, subjective to varying degrees), illuminating many more levels of an evolving process. Through equivalence the photographic object created becomes a reflection of both the external things it represents and the internal states of its creator. This reflective capacity is extended to the viewers, who re-experience this shared process in their own ways.

White remarked, “One should photograph things not only for what they are but also for what else they are.” and “Equivalence is a function, not a thing.” He did not mean to suggest that equivalence was merely a rhetorical device. Equivalence is more than a rhetorical device, not a simile that suggests shared commonalities (this is like that), not a metaphor that observes shared qualities through the power of transformation (this is that), but a process inclusive and transcendent of both. Like a simile its power starts with the recognition of shared qualities and like a metaphor its power lies in transformation, but an equivalent transcends both through a heightened state of self-awareness, even to the point of transforming the self through its accompanying effects of clarity and commitment.

A change of perspective is a change in state. Jean Piaget reminds us that, “What we see changes what we know. What we know changes what we see.” Perception changes reality – if only but not necessarily only because we are a part of reality. The more conscious the perception the stronger the change. Furthermore, the quality of consciousness one engages perception with influences what is perceived, what is produced, how it is received and the consequences that has. Acting on what one observes, choosing and sustaining one thing / quality amid many others, reinforces that state of being and this is particularly true if during observation one creates something tangible and durable and never more true if multiple related works are created. Often, during the process of manifestation perception continues to change, further extending this process of revelation and transformation.

Resonance is a consequence of equivalence. What we create can transform us. We then become cocreators, creating not only things and ideas but selves. What we create can also transform others, triggering cascades of sympathetic vibrations, if we imbue our creations with a persistent resonance, brought on by intensity, clarity and connection (connection to subject, medium, self, and others). Through the experience of art, the powers of perception and transformation can be awakened, in both the ones who create directly and the ones who reperceive indirectly. Just as whether something is seen or unseen depends on a degree of sympathetic vibration, whether this capacity is activated depends on whether an equivalent resonance is produced in the viewer, which is influenced by the clarity and intensity of transmission and the capacity of the viewer to receive it. In this process, the connections between all things are highlighted. In this light, photography, like all forms of art and many other disciplines, is an agent for heightened perception and thus an agent for change.

Equivalence is born out of a state of being and the equivalent is a record of and a catalyst for that state of being, which can be reenacted by others. Equivalence is a process of revealing and exploring not only our greater nature but also our connection to and unity with a greater spirit / energy field. Equivalence is a shared lived process of revelation and transformation. Equivalence is not a process reserved only for photography, it is possible in every medium, it is not only for artists, but for each and every individual. It is universal. The question that still burns is not does it happen, but when it happens how intensely and with what quality does it happen?

Stieglitz set a shining example for us all. He demonstrated that the full power of our photographs lies not in special subjects or moments but in what we bring to the picture, which can be much more than technical skill, compositional prowess, and cultural awareness. Through photography we can simultaneously bear witness to things / events, affirm our connection / participation with them (even if only as observers, no small thing), and clarify our understanding / interpretation of the confluence of everything that is brought to bear in each moment and the continuing resonances they produce. More than an intellectual interpretation or emotional expression, this is a process of holistic integration. The photograph can be much more than a material trace of another material; it can even be much more than a trace of light and time; it can also be a trace of spirit, the energetic confluence of body, mind, and emotion, either single or multiple.

White reminds us that this process of self-realization is open to everyone, “With the theory of Equivalence, photographers everywhere are given a way of learning to use the camera in relation to the mind, heart, viscera and spirit of human beings. The perennial trend has barely been started in photography.” Though all photographers do it, not all photographers do it with equal clarity or intensity. Regardless of what level they engage this process, whenever photographers break through to new levels of consciousness the results are transformative for the photographer and the viewer and even the viewed, sometimes subtly and sometimes dramatically.

Read Minor White’s essay Equivalence: The Perennial Trend.

The exhibit Seeing The Unseen: Equivalence In Photography opens in NYC at Soho Photo Tuesday, May 7.