Enjoy this collection of quotes by Hiroshi Sugimoto.

“My method is different from the one most photographers use. I do not go around and shoot. I usually have a specific vision, just by myself. One night I thought of taking a photographic exposure of a film at a movie theater while the film was being projected. I imagined how it could be possible to shoot an entire movie with my camera. Then I had the clear vision that the movie screen would show up on the picture as a white rectangle. I thought it could look like a very brilliant white rectangle coming out from the screen, shining throughout the whole theater. It might seem very interesting and mysterious, even in some way religious.” – Hiroshi Sugimoto

“Fossils work almost the same way as photography… as a record of history. The accumulation of time and history becomes a negative of the image. And this negative comes off, and the fossil is the positive side. This is the same as the action of photography.” – Hiroshi Sugimoto

“When people call me a photographer, I always feel like something of a charlatan—at least in Japanese. The word shashin, for photograph, combines the characters sha, meaning to reflect or copy, and shin, meaning truth, hence the photographer seems to entertain grand delusions of portraying truth.” – Hiroshi Sugimoto

“People have been reading photography as a true document, at the same time they are now getting suspicious. I am basically an honest person, so I let the camera capture whatever it captures… whether you believe it or not is up to you; it’s not my responsibility, blame my camera, not me.” – Hiroshi Sugimoto

“Humans have changed the landscape so much, but images of the sea could be shared with primordial people. I just project my imagination on to the viewer, even the first human being. I think first and then imagine some scenes. Then I go out and look for them. Or I re-create these images with my camera. I love photography because photography is the most believable medium. Painting can lie, but photography never lies: that is what people used to believe.” – Hiroshi Sugimoto

“It’s pre-photography, a fossilization of time, … Americans have done the Zen garden to death. I wanted to do something different.”

“I didn’t want to be criticized for taking low-quality photographs, so I tried to reach the best, highest quality of photography and then to combine this with a conceptual art practice. But thinking back, that was the wrong decision [laughs]. Developing a low-quality aesthetic is a sign of serious fine art—I still see this.” – Hiroshi Sugimoto

“If I already have a vision, my work is almost done. The rest is a technical problem.” – Hiroshi Sugimoto

“Art is technique: a means by which to materialize the invisible realm of the mind.” — Hiroshi Sugimoto

“I’m inviting the spirits into my photography. It’s an act of God.” – Hiroshi Sugimoto

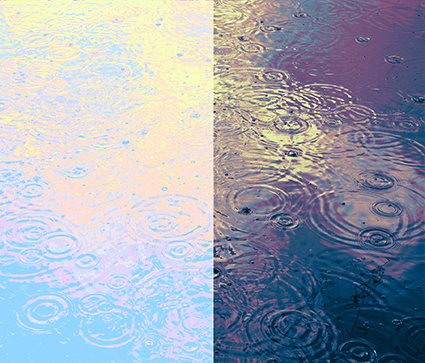

“Water and air. So very commonplace are these substances, they hardly attract attention―and yet they vouchsafe our very existence. The beginnings of life are shrouded in myth: Let there water and air. Living

phenomena spontaneously generated from water and air in the presence of light, though that could just as easily suggest random coincidence as a Deity. Let’s just say that there happened to be a planet with water and air in our solar system, and moreover at precisely the right istance from the sun for the temperatures required to coax forth life. While hardly inconceivable that at least one such planet should exist in the vast reaches of universe, we search in vain for another similar example. Mystery of mysteries, water and air are right there before us in the sea. Every time I view the sea, I feel a calming sense of security, as if visiting my ancestral home; I embark on a voyage of seeing.” – Hiroshi Sugimoto

View 12 Great Photographs By Hiroshi Sugimoto.

Find out more about Hiroshi Sugimoto here.

Explore The Essential Collection Of Quotes By Photographers.