4 Magnificent Maine Lighthouses Nearby

Maine has over 60 lighthouses.

While some lighthouses on islands take preparation to access, many are easily accessible.

Four of the most famous lighthouses are 15-45 minutes from Caponigro Arts, and they’re all quite different.

(Click on the images or titles to locate them on Google Maps.)

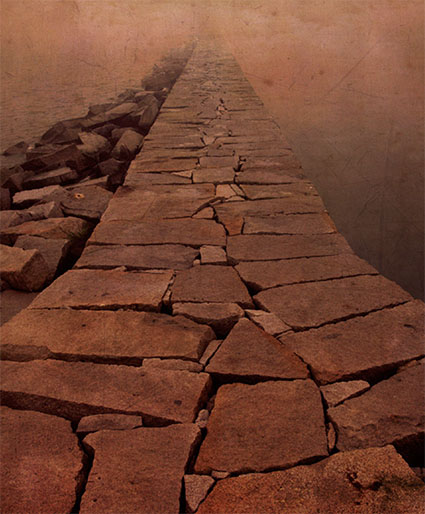

Rockland Light is accessed by walking the massive one-mile-long stone breakwater. It’s magical at sunrise, sunset, and in thick fog.

Owlshead Light is reached by a long wooden stair, just beyond the keeper’s house, because it’s perched high on a hill overlooking the Rockland harbor (including Rockland Light) and beyond to nearby islands.

Marshall Point’s light and the house are separated by a long elevated walkway over a rocky beach pointing to the surrounding islands. Made more famous by the movie Forrest Gump, it rests near Port Clyde (where you get the ferry to Monhegan Island).

Pemaquid Light towers over the magnificent slabs of granite, which are constantly tossed in wild surf, but always accessible no matter what the tide. It offers 180-degree views of the open ocean, which are stunning at both sunrise and sunset.

Crazy Easy Way To Fix Mask Edges In Lightroom & Camera Raw

3 Ways To Refine Adobe’s Select Subject Masking Results

Glacial – The Alex Ferrone Gallery – July 15 – Aug 13

Glacial

July 15 – August 13

John Paul Caponigro, Eleanor Goldstein, Ryland West

“This exhibition presents the stunning capture of Antarctica’s glacial landscapes by noted photographer John Paul Caponigro (ME); striking Arctic evening icescapes by painter Eleanor Goldstein (NY); and ephemeral portraits of Alaska’s polar masses by photographer Ryland West (NY).”

1 – Saturday, July 15 – Opening

Works will be on display in both the gallery and the barn.

2 – Saturday, July 29, 3:30 pm – Artist’s Talks

Join us for the Artist Talks to learn of the artists’ firsthand witnessing and artistic documentation of the threatening disappearance of these majestic icy masses due to climate change.

3 – Sunday, July 30, 1 pm – Reading In The Barn

John Paul Caponigro and guests will read thematically related poetry and creative nonfiction.

4 – Sunday, July 31, 9:30 am – NPR on WLIW with Gianna Volpeg

Join us for great conversations!

Enjoy The 2023 Camden Festival Of Poetry Online

I read at 43:30.

I read at 11:11.

The 2024 Camden Festival Of Poetry Is Coming!

The keynote will be Padriag O’ Tuama.

It’s free and open to the public.

2023 Camden Festival Of Poetry Highlights

New Features In Photoshop 2023 That Are Easy To Overlook

.

The new Photoshop 2023 non ai features are easy to overlook – but really useful!

00:00 Intro

00:20 Adjustment Presets

02:12 Making your own Adjustment Presets

04:33 Color grade with new gradients

06:15 Add point of light

06:56 New Gradients on Masks to blend layers

08:04 Remove tool in Photoshop

08:54 Contextual menu bar

Find out more from Colin Smith at Photoshop Cafe.

Learn more in my digital photography and digital printing workshops.

5 Powerful Ways You Can Use Space In Your Images

Spacey

Spacious

Gracious

Nice Fit

Compact

Packed

Impressionist composer Claude Debussy famously remarked, “Music is the space between the notes.” Space is just as important for images as it is for music. While the spaces are different in the final products, one is temporal, and the other is physical, space is equally important in both forms of art. As with music, in images, there’s a missing third dimension of space. Because music is usually abstract, it can be freer from the concerns of creating the illusion of depth, something that is essential in representational images. There are many ways to work with space, using tools like color, line, and texture to create distance, scale, and negative space, among other things. There are even many kinds of space and many kinds of spaces. How you treat space in your images speaks volumes. It reveals your deepest concerns and the vision through which they are expressed.

Distance From The Frame

How far you place elements relative to the frame can have a profound impact on a composition.

4 Tools You Can Use To Control Focus And Flow When Sequencing Your Images

Viewers search for significant changes between images presented together and the significance of the changes between them. It’s continuity. Every screenwriter needs to create it. Every storyboard needs to interpret it. Every director needs to guide it. Every editor needs to refine it. If you’re a still photographer, you may be called to do all of these things.

Continuity lies at the heart of the art of visual storytelling. The types of images selected and the transitions made between images presented in groups are powerful tools for visual communication. Sequences can provide useful comparisons and contrasts between separate images. They set a pace and rhythm for looking. Carefully orchestrated, they can create the illusion of moving in time, forward or backward, linearly or non-linearly. The best sequences make images, both collectively and individually, clearer, more meaningful, and more moving.

Photographers can use continuity to guide explorations on site and find more images; use a storyboard as a checklist to make sure no angle goes uncovered. Photographers can use continuity to find missing gaps or resolve challenging transitions in ongoing projects, update a storyboard and find out what you’ve got too much of and what you don’t have enough of, or find bridges to connect disparate images. Photographers can use continuity to edit, sequence, and present existing work more effectively; fine-tune an existing story to make it richer and more compelling or create a new one.

There are many classic strategies for sequencing images and creating transitions between them. They’re tools, not rules, that can be applied in many ways. How you apply them ultimately becomes a part of your style.

Because of persistence, this pair of images reads as one unit or a serial image.

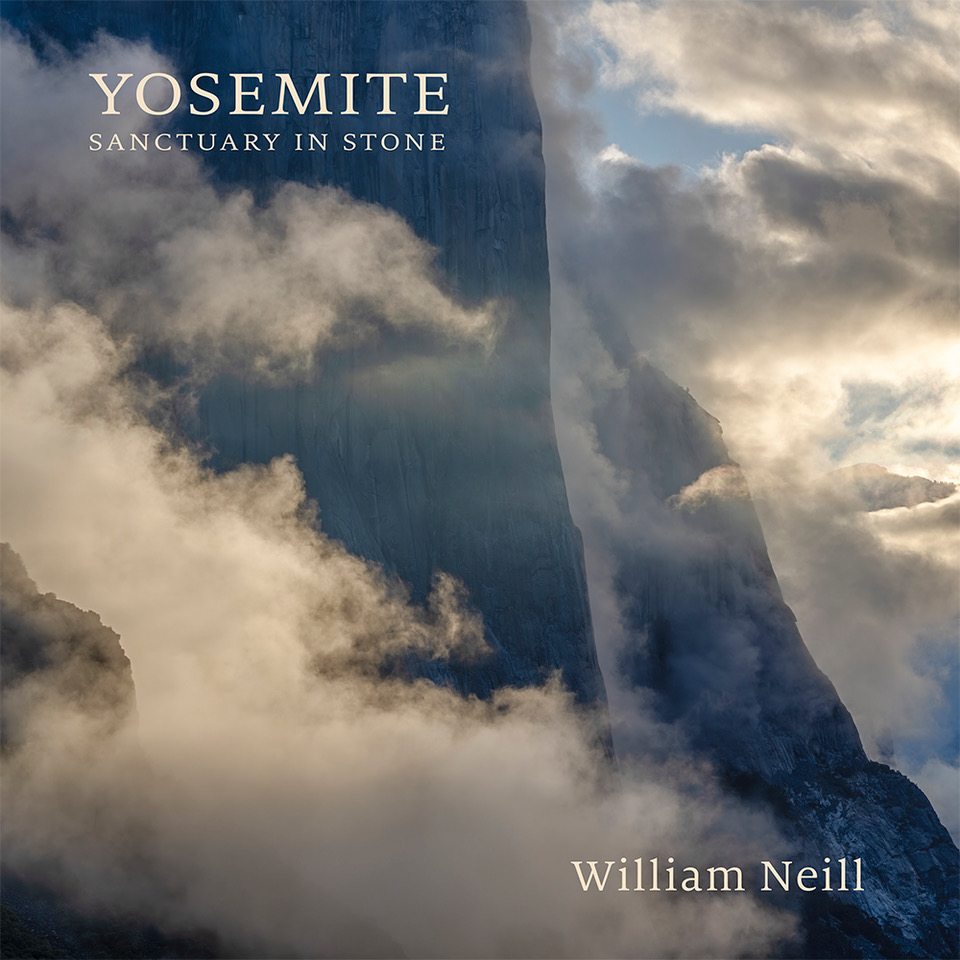

William Neill’s Yosemite: Sanctuary In Stone

Order this book here.

Pre-Order offer ends on July 9.

11.6 x 11.6″

168 pages

128 photographs

When one thinks of photography in Yosemite, one thinks first of Ansel Adams and then William Neill. And for good reason. When you love a place, you look at it differently. William Neill’s photographs of Yosemite clearly demonstrate a lifelong passion for this very special place, made even more special by his dedicated attention to it.

“Now it is finally time to realize this project I dreamed of 20 years ago. Yosemite: Sanctuary in Stone is a personal collection of photographs reflecting 46 years of dedication to this wonderous landscape. Living here, photographing Yosemite and its vicinity, I have been working towards this dream for much of my lifetime.” – William Neill

I’ve seen the preview. You’re in for a treat!

Until you see it, get to know William Neill better in these collected resources.