.

.

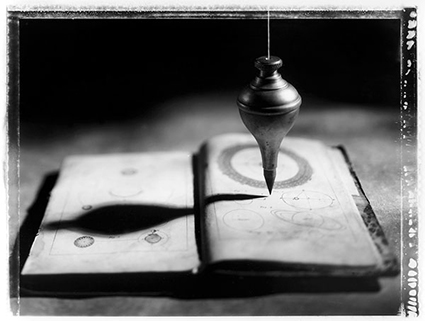

Sean Kernan

Watch video at the bottom of this page.

View 12 Great Photographs by Sean Kernan.

Sean Kernan, born in York City in 1942. He studied English at the University of Pennsylvania, thinking he might be a writer, but he stumbled into theater instead, and then onward into photography. He feeds his body with advertising and his soul with personal work, and he writes occasionally. He has taught at the New School, ICP, and the Santa Fe and Maine workshops. His book, THE SECRET BOOKS, with a text by Jorge Luis Borges, will be published this fall.

John Paul Caponigro Tell me how you became interested in the artist Bustos’ work and how that led to your Mexican portraits.

Sean Kernan I came across the portraits of Hermenegildo Bustos in an Italian magazine just before I was going in to teach a portrait class, and I was bowled over. His paintings were so alive, so penetrating, and so perfectly specific to each subject. The people’s faces just shone out from his rather formulaic figures. I showed the work to my class and said, “If you spoke to these people they’d speak back. THAT’S what a good portrait can do.” In his life he worked only in his small home town – now named after him – but in time he has been recognized as one of Mexico’s great painters.

So a few years ago I was in Mexico on vacation, and I visited the museum that has the biggest holdings of his work. It was great to see them in actual paint, and to see the incredible sense of honesty and presence in them. It gave me something to aspire to.

Afterward I went and had a drink in the Plaza, and as I sat watching the people walking around, I thought, “They’re all still here.” It seemed that the great grandchildren of his subjects were all around me. So with the help of a friend I was able to get someone to work with me in Mexico, and I went back a few months later and set up a small studio in the town he’d lived in and just went out and pulled people in off the street to make their pictures.

I hadn’t done portraits for years, and this reintroduced me to the sweet pleasure of just gazing into people’s faces, which for some reason they’ll let you do if you’re a photographer. The project continues to expand. I’ve made three trips to Mexico, and I hope to travel to Cuba and Italy to work on it in the next year or so.

JPC Unlike Jock Sturges, who emphasizes getting to know ones subject over time and outside of photography, not directing the subject, and the complement being paid by the presence of a large camera, you speak of the benefits of making portraits of strangers and an “intimidating paralysis” created by the view camera. There are indeed many paths. Tell me more about your methods and the benefits you’ve found from them.

SK I used to believe that knowing someone as well as you could, that making yourself vulnerable to them, was very important and even crucial to photographing them. But I didn’t know these people at all, and our mutual understanding was limited by my Spanish skills, which are those of a two-year-old. On top of that, I was working with a view camera, lens wide open, bellows racked all the way out, on top of the subjects, really. But since to them I was off behind that camera someplace, in a real sense they were looking into a glass eye, with a mix of apprehension and faith and a grain of trust. Anyway, I think the rather overwhelming set-up called forth the sense of presence, alertness and even bravery that I see in their faces. But the relationship the pictures show seems to be between the subject and the unknown. They’re just there, just hanging in space with their lives written all over their faces. I tried to just stand back as much as I could.

JPC It seems there are three major agendas for making a portrait to document, to flatter, to reveal. Though some of the people in these images might evoke notions of classic beauty, these images are definitely not glamour shots, meant to flatter. They could be considered documents, yet I sense these are not merely historical records; these are not famous individuals so I would expect extraneous texts to inform me further. Portraits of the “common man” have been considered for their historical and artistic merit. August Sanders’ portraits are valued for both qualities. I suspect these would too. So this all leads me finally to revelation. What kinds of revelation are at work here?

SK What is revealed? I hadn’t thought of that question. I have to say that what is revealed to me lies beyond any ideas I had for the pictures. Len Jenschel reminded me recently that Gary Winogrand had said that he photographed because he wanted to see what things looked like in photographs. I think that I began by wanting to see what kind of pictures this intense way of working might produce, and honestly I didn’t have any idea beyond that. There was no planned outcome, none of what I recently heard a composer call “The Fallacy of Intention.”

So, I didn’t want to document these people or flatter them. I guess I just wanted to be with them and take them seriously and see what might come of that, what we might make together. I am gratified that their humanity reveals itself. I’m gratified that their eyes look back. And because my approach was so in-your-face on the one hand and a little remote on the other, I think that the subjects were more present. I talk as though I just kind of showed up and ran the machines, but I was there, I chose the project and the people, edited the images to print, so of course I’m not just a bystander.

I’d love to say something more intelligent about this, but I don’t know that the process had much intelligence in it. Maybe that came later, if it came at all. I DO wonder how Bustos worked when he painted. My guess is that he was a bit chummier with people than I was.

JPC I’m curious about your impulse to create a division within the total image (quite often like the division found between the leaves of a book) or to make one image out of more than one piece. Sometimes objects within separate portions are slightly out of scale or out of sync – things don’t quite line up perfectly. What’s happening here?

SK The images are not so much divided as they are different images joined. I think I’ve always envied painters who could layer up impressions and observations and give a larger sense of a person. It’s as though a painter accumulates a series of transparent faces that add up to a person. The photographer always gets stuck with whatever he can tease out of a sixtieth of a second, and if he does well he can print the exposure that has implications and resonances.

At first I just shot two halves and joined them kind of seamlessly. Then I realized it became more interesting if the pieces didn’t quite go together, and I started to play with small differences. Finally, of course I went completely overboard and joined up parts of different people and so forth. In the end I think that the dislocation has to reflect something real. You can’t just stick things together and say, “Look! Art!”

JPC What do you feel the benefits of the elements of chance are?

SK The benefits of chance are enormous, but you have to watch out for them too. Chance gets me beyond whatever I had in mind when I started to work. It comes into play when I let things happen and then chase alongside them and grasp them on the fly. It’s like two acrobats, one of whom doesn’t know that he’s an acrobat. But the artist is responsible to what chance gives him, and just setting it down without taking it in and manifesting it again in the heuristic process is not enough. Maybe it’s that chance is happening all the damn time, and it’s the artist’s intentional work with it that strains artworks out of the soup.

I’m inclining toward the idea that the working process of art is a lot more thoughtless than I once imagined – thoughtless but not stupid. Somehow the pictures that work out just the way I wanted them to are the ones I lose interest in soonest. The expectation has become the limit. And I think that the way to take something beyond your own expectations is to leave what you see unnamed and beyond concept for as long as you can. I want to work as far beyond what I know as I can get, and the gate to that beyond lies exactly between seeing and naming. For me the process goes like this:

Ah! Ah! Beautiful!

What a beautiful tree!

A maple, is it? I think so.

Yes, a sugar maple.

With the sunlight glowing through it.

Like that painting I saw. Who was it by?

Some impressionist, I think.

Not one of the great ones. But good.

And so on, down the tubes, from seeing to Art to Art History, to half-formed opinion. This categorization takes your mind narrower and narrower.

So you want to float in that space of awareness as long as you can, keeping all possibilities alive so they can become clearer, then you pull down one that is BOTH unexpected and makes perfect sense.

Here’s an example from writing. Annie Proulx writes about a flock of ducks taking off as looking like a deck of cards flung in the air. It is the unexpectedness of the image that wakes us up so we really see something, and the rightness of the image that affirms what we have seen in the mind’s eye. The satisfaction comes from exactly the principle of waiting, I think. The possibilities are kept in the air, and when one is pulled down, it is unexpected AND makes perfect, loony sense at the same time, and thus makes us see things anew.

JPC Yes!

We’ve been discussing many forms of art, particularly writing. On the one hand there is Ryokan and Basho’s haiku on the other hand there is Dante and Milton’s epic poetry. There is painting and photography. There’s the decisive moment and the photo essay. Each involves a different accumulation of effort through time and we may want to make some distinctions between quantity and quality and their relationship. There is a pervasive notion in our culture that longer and/or harder is better? And this kind of standard that can lead some to thinking certain kinds of photography or photography in general is a lesser art form.

Case in point, I’ll never forget the time when one of my friends introduced himself to my father for the first time, “Oh, you’re that photographer. Gee I’d like to have your profession. All those hundred and twenty fifths of a second, what’s that add up to, a twenty minute career?”

SK Well, I confess I’m one of those who thinks photography is a secondary art form that is sometimes practiced by primary artists, like your father. I think photography is fairly easy to do, and perhaps long and hard are good for one’s work because they demand that one pay greater attention, and so one sees more possibilities.

I keep thinking about what we talked about, the matter of art work being difficult. We talked about the time work takes, and I think we agree that time is not the only factor. If it were, we’d see macramé in museums. With some of the “instantaneous” art forms – photography, Zen calligraphy, some poetry – all the time is invested in the practice, and the execution looks simple and quick.

This leads to the thought about the time that it takes to really apprehend a work. Photography is like a skyrocket, the novel is like a candle. Photography and poetry hit with a strong, nearly instantaneous impression, and they do their work in memory for a long time after we walk away from the work. But a longer form–particularly the novel – feeds it’s line into your being for a week, a month, like a long thin wire that cuts a new channel through you and strings you together in a new order if it’s good. Its Aha! versus Hmmmm … and I wouldn’t want to choose between them. But after all those years of work at Aha!, I’m slowed these days and made more contemplative by the Hmmmm of writing. It’s like walking instead of driving. I see different things. Of course, it takes me a hell of a lot longer to get anywhere.

JPC Isn’t that the crux of the matter we’ve been discussing? The process or the mode fosters a specific kind of perception. It is tempting to attach the words “the process” to the materials and the physical aspects of work, and they are important and interesting, still I feel it’s even more interesting and rewarding to look at “the process” as engaging in a discipline or specific mode of perception and becoming aware of the resulting psychological effects that activity nurtures. In this respect the various artistic disciplines are not as different as they would seem. It’s no wonder we draw inspiration from so many sources outside our chosen mediums.

SK Absolutely! I think the process is in the elimination of conceptions and cleansing the mind, then in claiming the awareness and manifesting it in a work. It’s not in sizing the canvas or coating platinum onto paper. It can happen while you do those things but those things aren’t it.

JPC Again, “empty mind.” Life as meditation.

You’re a very creative teacher, as well as photographer and writer. Tell me briefly a few of the unusual things you do with your students and your thoughts on the benefits of thinking outside traditional bounds. In reference to unorthodox methods you said, “It opens up so many other ways to experience something beyond seeing what something looks like. After all, the next thing a photographer needs to know is what a thing feels like.”

The whole basis of this odd class I’ve evolved lies in setting photography aside so we can see other things which may then become photographs or not. As the great painter and teacher Robert Henri said, “The object, which is back of every true work of art, is the attainment of a state of being, a state of high functioning, a more than ordinary moment of existence. In such moments activity is inevitable and whether this activity is with brush, pen, chisel, or tongue, its result is but a biproduct of the state, a trace, the footprint of the state.” So in the class we go after that state by doing observation exercises, playing theater games, doing some Tai Chi, writing a little bit, all in order to open our eyes in ways that we tend not to do in photography, and what we experience in doing this we can apply to photography or not, but the point is to wake up and stay that way. Now of course one can’t really teach this kind of creativity, but one can set up a force field in which it can happen more easily.

JPC In a charged state excitation is more likely to occur? You said something very interesting about intensity, “Look at the photographs of Mary Ellen Mark or Duane Michals. They are so focused, and that focus alone brings other people to their photography.”

SK Actually this thought comes from the theater games we play in class, and what comes out of it is really important stuff. Alan Arkin came and worked with my class once, doing various improvs and theater games. It was great to get photographers out of their cherished observer position and interacting with things. But the thing that was most striking, and the whole point for me, was that when people committed to playing the game with their whole being, that commitment itself had power, and it had the effect of bringing other people into the game. On the other hand, if someone was self-conscious and uptight and kept slipping out of the game cracking jokes or relating to the audience, it broke up the game and it all became meaningless and uninteresting. You can see it in a great actors work – look at De Niro, or Streep, or Arkin. They can just stare into the air and you’ll sit and watch them, watch their intensity. And I realized that some of the best photographers I know have that same kind of intensity. It shows in their work. Their intense staring generates its own power, and we respond by staring with them.

JPC There have been a few times when you’ve mentioned photographs that are “skillfully crafted.” I’m sensing that when you describe them this way that while you admire them technically something is missing. What’s missing?

SK Referring back to acting again, one might see a well- crafted performance in which one is aware that one is seeing Romeo and Juliet being well acted, and another in which the tragedy of Romeo and Juliet tears you apart. So the thing that is missing is the thing that brings it to life right there in the audience’s own hearts. I think it is the complete belief of the actor/artist in the reality of what they’re doing that makes it real.

JPC How do we know when something’s missing?

SK Great question. When is something good? The first question I tell students to ask in the first critique of a class is not is the work good, but is it alive ? Some great conductor said that everyone knows that the music is between the notes. So if every thing looks right and it still feels wrong, or lacks resonance, or if it refers mainly to other photography and not to seeing, to awareness itself, you should sniff elsewhere.

JPC Nice. And how do we know when it’s not missing, when we’re in the presence of that something? For me one of the best indications is a shared absence of breath.

SK There’s a great haiku which goes something like:

Ah, ah! Spring!

Ah, great, great Spring!

Ah! Great!

The poet is knocked into inarticulateness and can’t get out, just has to stay there. So it is for me when something is really, really working. There’s nothing to say about it. I think that if there’s a kind of art that I’d like to make it would be art that is beyond comment. I don’t think I’ve done this yet. On the other hand, there’s also work that just gets under your skin, sometimes in ways that are not necessarily pleasant. I have a real appreciation these days for work that abrades me into awareness. Since abrasion seems to be a currency of our time, art today would have to use abrasiveness, just as Giotto used holiness in the 1500’s.

JPC The novelist and the photographer both depend on keen observation of detail and yet an overburgeoning wealth of literal description rarely seems to be the desired goal of either. You mentioned that in photographing books, often you would want the text to serve a suggestive function rather than a descriptive (even illustrative) one. I imagine that impulse is strong throughout your work.

SK I have been working on this novel and it is like making this big, enormously complex structure in which things you say on page 15 pay off on page 285. It is a huge complex construct in which a reader can wander, and you have to leave little bits of nourishment, of specific meaning, for him in any number of places because you can’t tell when he might need them. By contrast, a photograph hits a viewer more or less at once, and you want to give enough detail so that he can get what he needs, but you don’t want to mire him in it. In each case, though, you give the viewer or reader some pieces of the puzzle so he can assemble the thing himself, in his own experience, in his own time. It lets him invent the piece inside for himself. When that happens, you’ve passed along, not the words or pictures or even ideas, but the state that Robert Henri talks about. If getting in the state is one great reason for doing art, then passing it to others closes the circuit and lets the power surge beyond our small minds. It’s a way of approaching the divine – one of the few ways left to us, I think.

Read More Photographers On Photography Conversations.