Metadata Panel – Julianne Kost

In this quick tip Julieanne shows how to add presets/templates using the Metadata panel.

View more Photoshop Videos here.

Learn more in my digital photography and digital printing workshops.

In this quick tip Julieanne shows how to add presets/templates using the Metadata panel.

View more Photoshop Videos here.

Learn more in my digital photography and digital printing workshops.

“Julieanne Kost reveals there is far more to the History panel than simply un-doing mistakes. Learn as she reveals little known shortcuts for working with the History Panel, including how to fill with the History Brush, as well as a fluid method for painting between snapshots with no layer or masking knowledge required!”

View more Photoshop Videos here.

Learn more in my digital photography and digital printing workshops.

![]()

Adobe has released updates for Camera Raw (6.6) and Lightroom (3.6).

New cameras are supported.

New lens profiles have been added.

Bugs are fixed.

See the Lightroom Journal for a full list of details.

Download the updates here.

Julieanne demonstrates how to update, rename and delete presets and templates in Lightroom.

Watch more videos on Lightroom here.

Learn more in my digital photography and digital printing workshops.

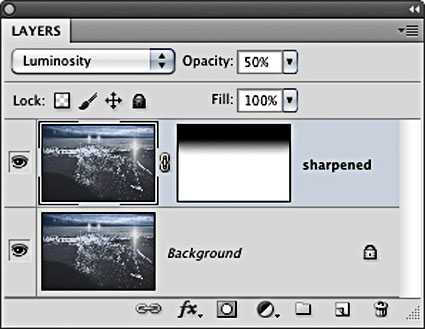

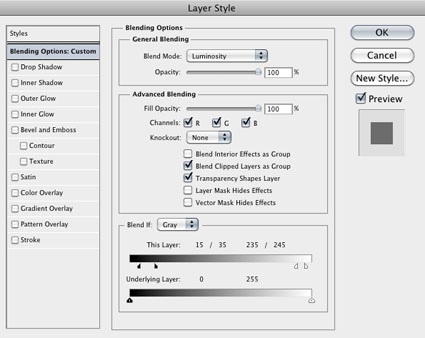

There are many reasons to use layers when sharpening your digital images.

Layers can be used to eliminate saturation shifts. Change the Blend Mode of a sharpening layer from Normal to Luminosity. Color noise will be reduced this way.

Julieanne Kost demonstrates the two most frequent methods for importing files into Lightroom. She discusses the advantages of each workflow, whether you’re importing directly from a card or importing images already copied to a specific location on your hard drive.

Watch more videos on Lightroom here.

Learn more in my digital photography and digital printing workshops.

In this quick tip Julieanne shows when to toggle Lightroom’s Show Photos in Subfolders feature and why turning it on might show a 0 photo count for your top most (parent) folders.

Find more Lightroom videos here.

Find Photoshop videos here.

Learn more in my digital photography and digital printing workshops.

In this episode of the Complete Picture, Julieanne Kost helps you decide which application is right for your workflow by explaining the differences between Lightroom and Bridge for managing images and assets.

View more Lightroom videos here.

Learn more in my digital photography and digital printing workshops.

Find out how Adobe Photoshop and Adobe Photoshop Lightroom work best together. This session reveals the most efficient way to move back and forth between these powerful applications, whether you’re editing a single image or an entire shoot. You’ll learn how to take advantage of export options, presets, publish services, Smart Objects, droplets, and more to automate your workflow and increase your productivity.

View more Lightroom videos here.

Learn more in my digital photography and digital printing workshops.

Matt Koslowski demonstrates Lighroom essentials – importing and organizing, developing, editing in both Lightroom and Photoshop, as well as printing and presenting your photos.

View more Lightroom videos here.

Learn more in my digital photography and digital printing workshops.