Approach Things In Many Ways

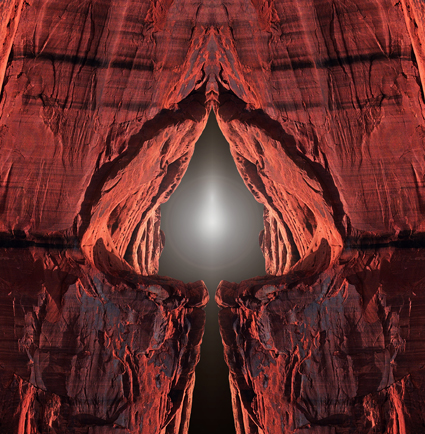

Triple Goddess, Aneth, Utah, 1996

This image was born out of synergy. It took multiple media to resolve this image and each one contributed something unique to the final result.

During a brainstorming session I used word associations to search for new possibilities. Only a few word pairs and phrases stood out of the hundreds that were generated, only some of which seemed related, including ‘floating stone’. What was it that made that pair stand out from all the others? Perhaps it was the reversal of expectations it contained, stones don’t float they sink. Perhaps it was something else, something less easily explained and more personal.

I slept on it. Shortly after midnight, I woke up in the middle of a dream of a floating stone. Dreams are rich sources of insight, which is why I make sure to always have something close at hand to record them. I quickly sketched the image. Why a sketch? I had already written the words down. In this case, an image would be more specific. And I went back to sleep. In the morning, when I woke up again, I saw the sketch at my bedside. It helped me remember the image in my dreams. I sketched many variations of the image, generating many possible compositions of the same subject and even found a few new ideas along the way.

That day, I went to my photographic archive and searched for the best material to bring this image to light. Along the way, the photographs I sifted through stimulated many new related ideas, which I also sketched. In the end I decided to use a stone that was much smoother, a sky that was more complicated, and hills that were smoother than the ones in my dreams. Even as I was compositing the three images into one, something new ideas emerged when I decided to make the mounds symmetrical. Influenced by everything that I had experienced between discovering the seed of the idea and its final resolution, the image had grown richer and evolved. Discovery can happen at each and every point in the creative process.

When engaging in creative challenges, if you approach things in multiple ways you’re sure to find a shift in perspective. Whether we’re looking for new ideas, solving problems, or seeking feedback about what we have produced, we often enlist many people with a variety of backgrounds and experiences who each have something different to contribute to our understanding. You can do this for yourself, by trying different things that will bring you a variety of experiences and new perspectives. Doing this is part of being well-rounded, well-informed, and thorough. You never know what you’ll discover, until you try it.

Questions

How many ways can you approach researching a challenge?

How many ways can you approach solving a challenge?

What unique contribution does each approach make to your understanding?

What unique contribution does each approach make to the final result?

Which is the best mode to start with?

Which is the best mode to end with?

What mode is best for a given stage of development in a creative challenge?

Is there an optimal order for mode shifts?

How long is it best to stay in one mode before moving to another?

When is it better to stay in one mode?

When is it better to move to another mode?

Find out more about this image here.

View more related images here.

Read more The Stories Behind The Images here.