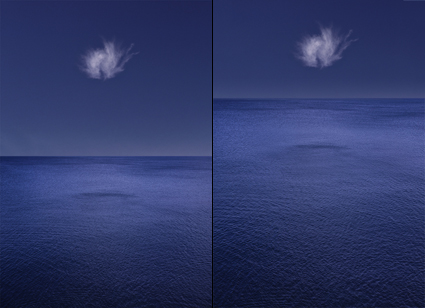

Oriens I, Death Valley, California, 1999

I missed the shot(s) the first time. When I got back from Death Valley, a friend said, “Zabriskie Point? Again? Well, I’ll bet you could photograph it in a way that hasn’t been done before.” I knew what she meant, but her comment actually clarified another idea for me.

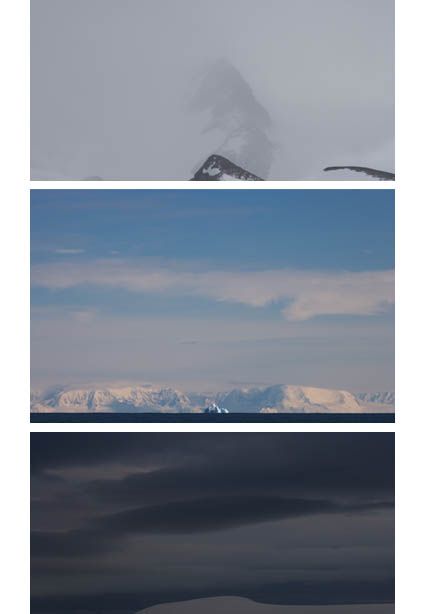

I had been deeply impressed by the way the light changed mercurially over time, continually transforming the landscape from pre-dawn through early morning. It first lit the blue-gray sky with pale pinks, then turned the far mountains from a cold brown to a hot coral, crept slowly across the valley floor to set Manley Beacon on fire (the crescendo in a magnificent symphony of light that most photographers favor), and continued to create moving pools of light in the foreground during a process that lasts for more than an hour. It is a wonder to behold and to fully appreciate it, one needs to be still and vigilant for some time. Its full impact cannot be found in a single moment. I found it in many.

The solution? Make multiple exposures of the same composition throughout changing passages of light and then blend them together to create the impression of an extended moment in time.

I had made exposures of sunrise at Zabriskie Point, but I hadn’t made the ones I needed now. I had to go back. It took a year and a half. Knowing that so many unexpected things often happen, I prefer to make flexible plans, so I wondered if I would return for an idea that ultimately wouldn’t work. I envisioned glorious light in every layer of the landscape. As I began making the exposures, I realized there was a flaw in my plan. If I selected the ‘best’ light in every area of the picture, all areas would demand equal attention. There would be no contrast. The final image needed shadow just as much as it needed light. I persisted, making exposures, without moving the camera for more than an hour, of every significant change in light – and shadow. My original plan was useful but it needed to be modified as it was executed based on specific conditions, new information, and insight. To succeed, I had to listen not just what was in my head but also to the place and the process.

Later, as I looked at my transparencies, the final solution presented itself. This new solution even highlighted my feelings about the place more strongly than my original idea. The result, different from my initial conception but consistent with my intention, achieves a dramatic lighting effect never before seen at one time. Yet, throughout time, a similar sequence of experiences has been witnessed countless times by so many.

The light on the foreground is unaltered, or to be more accurate, I should say is faithful to the transparencies that recorded it. The separate portions have not been modified substantially, nor were they modified unequally – there has been no dodging and burning. Instead, the light has been reorchestrated with time, faithfully representing the existing light(s) but changing what can be seen in a single moment.

Nothing in the foreground, midground, or background has been added or removed. The sky, however, is an addition from another location. I found the smaller sliver of sky contained in the original exposures made the composition cramped. It lacked the vast sense of space found in the desert. The sky had in fact, been the first indicator of the presence of the coming light, making a thousand transformations before its arrival. But the sky that morning was not particularly noteworthy. I could have spent a lifetime waiting for the perfect sky. I chose instead to incorporate another sky from another location that supported both the composition and the light. This sky I altered dramatically, both in tone and color. I did so to expressively complement the drama of the light below, to support it and not detract from it. While the lower half of the image is a matter of resynchronization, the upper half is a matter of recontextualization.

Neither method (resynchronization or recontextualization) yields a classically objective document. However, the results of their application may yield artifacts that are truer to our experience of events than traditional photographic practices. If applied in specific ways, they can represent certain aspects of events more faithfully, such as the passage of time.

Making this image changed the way I think about and experience the essential elements of photography – light and time.

How many ways can thinking more predictively about change aid your creativity?

How many new ways can you think about the fundamentals of your medium?

How can planning increase your creative success?

What can you do to encourage your plans to evolve?

Read more The Stories Behind The Images here.