Talk To Yourself

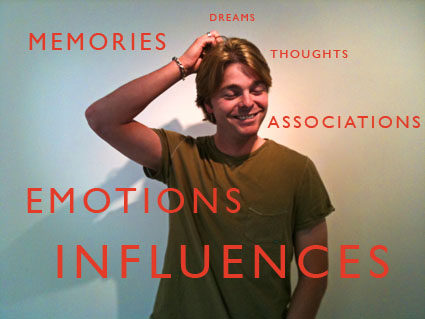

Talk to yourself. Don’t worry, it’s not crazy. We all do it. Speaking your mind can help you become clearer about what’s on it. It’s your choice, whether you decide to speak your mind silently in your head or speak your mind out loud, either alone or under the right circumstances in the presence of others. No one ever has to know how much you talk to yourself; they rarely know how much they talk to themselves. Everyone has an ongoing internal dialog. We see things, we hear things, we feel things, we do things, we react, and all the while we interpret what we’re experiencing. It takes years of training not to do this. Most of the time, we’ve become so accustomed to the familiar voice inside of us that we’re often unaware of what’s being said and who’s saying it. It seems natural to us. That’s just the way it is. But, in reality, that’s the way we are. If we actively listen to ourselves, we become more self-aware and realize we have many more choices available to us.

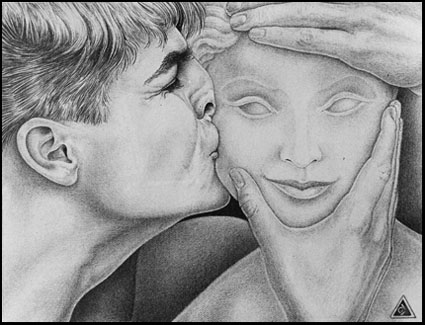

We may even come to realize that we have many different voices within us – aspects of ourselves that can be seen as being distinct from one another; a child, a warrior, a lover, a dreamer, a scientist, etc. We can make the life of our inner community richer and more dynamic by encouraging these separate voices to speak in turn and even to speak to each other. Over time we may even discover that each voice has a consistent set of concerns and perspectives and knowing this can help us decide which voice to call on in a given situation. This imaginative exploration can be extremely revealing. We not only come to better understand ourselves and what makes us truly unique, we also come in contact with vast sources of information and understanding that we often leave untapped. The best thing about listening to our selves is that we come to realize we have many more perspectives to draw from and opportunities to choose from than we had previously imagined.

If you really want to learn a lot, put a neutral moderator in charge of these conversations. His or her job is simply to listen and observe non-judgmentally. Nothing shuts down communication faster than criticism. At times your moderator may direct specific questions or make a motion to move on to other subjects. Later, when all is said, you can weigh the evidence, draw conclusions, and make decisions about what’s to be done or not done.

We all want to be heard. When was the last time you wished you had someone to listen to you? When was the last time you listened to yourself?

Go ahead, speak what’s on your mind. Who knows? Other people may want to hear what you have to say.

Find more inspiration in my Creativity Lessons.

Learn more in my Digital Photography Workshops.