How To Use An Image’s Frame Effectively & Expressively

The four most important lines of any image are the ones that are often least recognized consciously – the frame. Part of learning to make successful compositions is learning to become more conscious of the frame and how to use the forces it exerts on your images for desired effects.

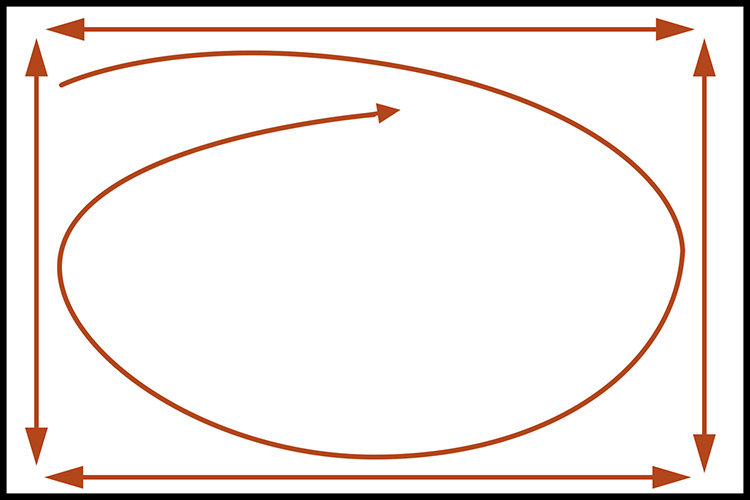

Watch The Movement of the Eyes Within the Frame

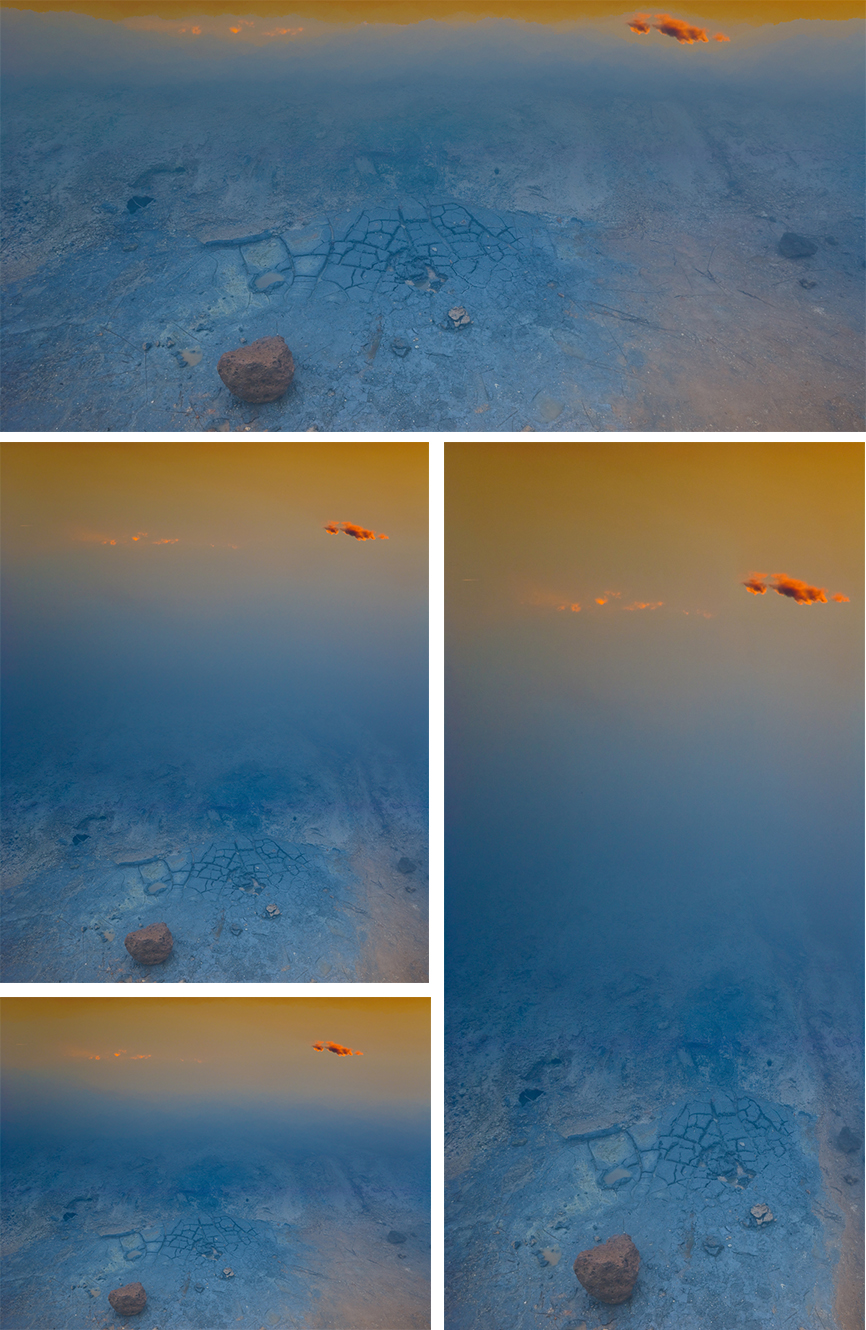

Whether visible or invisible, every line creates vectors of force that encourage the eyes first to move along it and second to bounce off it. The eyes search the frame in a consistent fashion and these tendencies influence our experiences of all compositions, no matter how diverse. The general tendency is for the eyes to move within the frame from left to right and top to bottom and then to return and repeat this process. The eyes quickly scan the frame itself (determining the limits of what’s included and by extension what’s not) before they scan what’s within the frame. On their first pass, rather than scanning each line of the frame precisely, the eyes quickly average the competing forces of the four vectors in a single sweeping gesture. Afterward, given time for a more careful examination of an image, the eyes may trace and retrace each line of the frame more precisely, until their quest for information is better fulfilled by other paths.

When it comes to motion one must always consider momentum, gravity, and resistance. Some motions, like falling (within the frame think top to bottom and left to right), are easier to get started and harder to stop than others, such as climbing (within the frame think bottom to top and right to left). Once a motion is started it tends to persist until stronger forces modify it. Place one or more barriers in the path of motion and it will shift and sometimes even reverse. Individual compositions work with these tendencies, whether subtly or dramatically, reinforcing, modifying, or working against them.

The motion of the eye within the frame

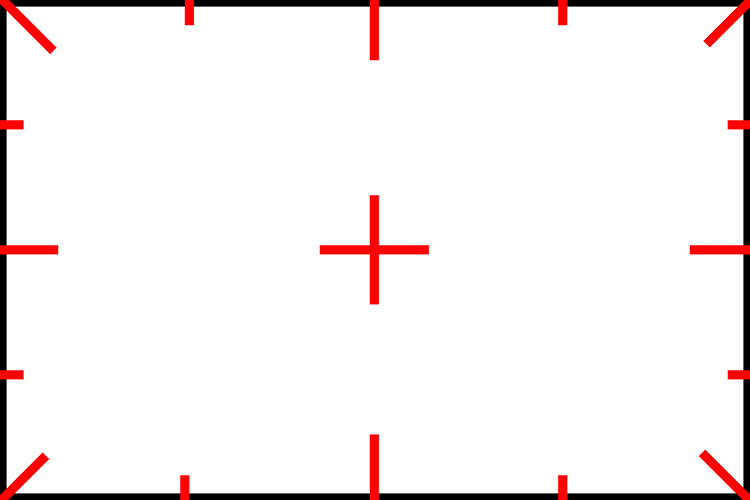

Powerpoints on and in the frame

Scan the Frame Consciously

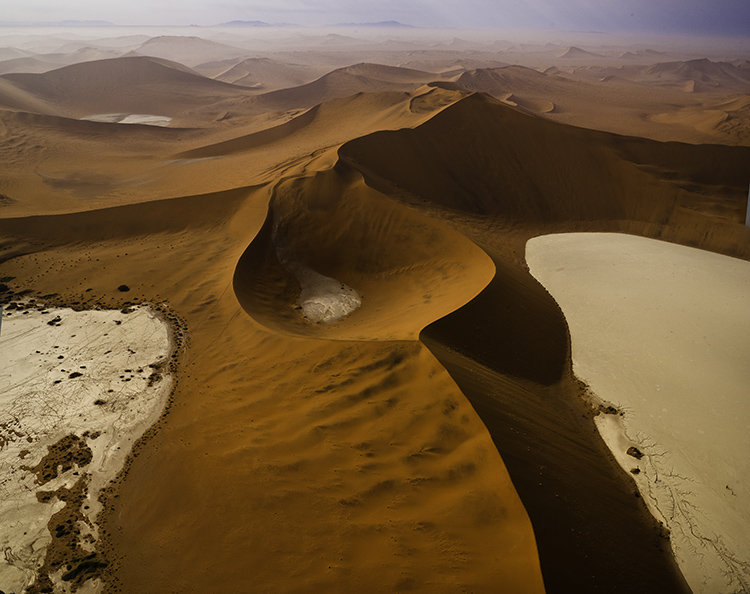

Always be conscious of the frame. Scan it. Consciously move your eyes around the entire frame. Anything that touches the frame exerts a stronger influence on a composition. (This is particularly true if it touches a power point, like a corner or the middle of a border.) If information that is not important touches the frame it becomes even more distracting. To make a composition stronger, frame it in a way that only important information touches the frame.

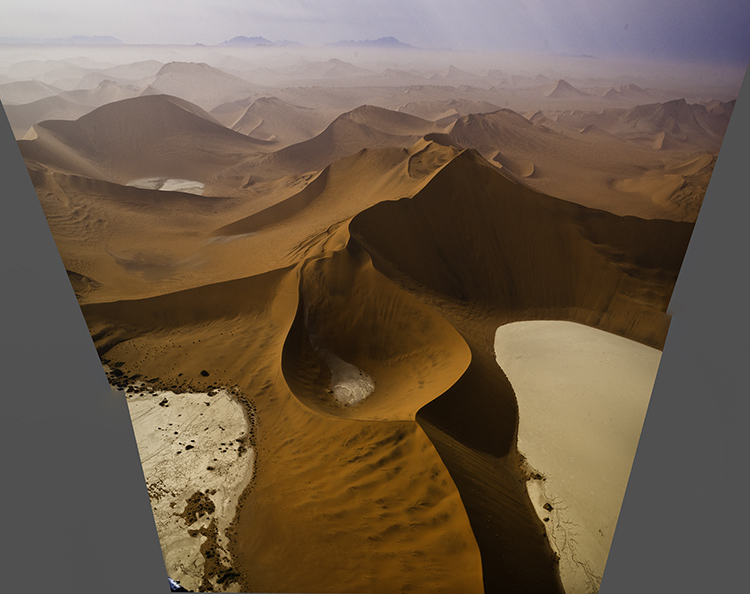

By emphasizing more important elements and deemphasizing less important elements (or eliminating them entirely) you make images stronger. Before exposure, you have an opportunity to make the composition stronger through reframing. After exposure, you have an opportunity to make a composition stronger through cropping (this eliminates other image information that may or may not be significant) and/or retouching (this includes the image information surrounding the flaws).

Use Proximity to the Frame

Frame loose or tight? How you place elements relative to the border of the frame can have a profound impact on any composition.