Photographer Arthur Meyerson – His Top Five Influences

I talked with Jeff Larason (The Crit House) about my top five photographic influences.

Find out who they are and why in this video

“Build a large visual library.” is Howard Schatz’s excellent recommendation for photographers at any stage of their journey. For decades, he has continued to do this himself well into a highly successful career, consuming images voraciously. While he haunts bookstores, he doesn’t mean just buy a lot of books with pictures in them. He means to learn to see (more versatilely, contextually, and deeply) look at a lot of images.

What are some of the benefits of exposing yourself to more images?

1 You’ll see more possibilities.

The amazing variety of images (subject, style, context) will inspire you to try some of the things you see.

2 You’ll see more of what’s been done.

Becoming familiar with a medium through its history, you’ll see the sensibilities of eras, past fads, current trends, and enduring themes.

3 You’ll develop a repertoire.

Identifying successful techniques (composition, exposure, development) that have been repeated by many different artists is the first step to incorporating some of them into your practice.

4 You’ll see what hasn’t been done.

Once you know what’s been done, you’ll be able to imagine what hasn’t been done and may fill that gap, either with a bit of twist or a giant leap.

5 You may even combine things that have been done into new combinations.

A little of this mixed with a little of that may become a new thing.

There are more benefits to exposing yourself to more images, but isn’t this enough to get started? The principle is simple. If you look more, you’ll see better. I recommend you make it your lifelong practice. It’s a pure pleasure.

Complexity

Intuited Order

Eliot Porter saw a more complex geometry in nature.

All types of artists look closely at their influences; particularly as they’re finding their own voice, or at key stages in their creative development, for many, it’s a lifelong process. The comparisons and contrasts are illuminating and inspiring. You can get more out of this process if you simply state the nature of an influence in one sentence, one phrase, and one word.

Doing this will help you to both better understand and more effectively communicate the nature of your influences. Usually, this doesn’t happen instantly. First, it takes identifying who or what the influence is. You probably have so many influences that you’ll want to choose the ones that are most important to you to develop. Which are those? If all you do is identify this, your time will be well spent. Go a little further and you’ll get more benefits. Take a little time to uncover your thoughts about an influence; associate freely. Finally, take a little time to edit what you’ve gathered; cutting the words that aren’t quite right, keeping the ones that are, and searching for even better ones. Very often, the connections between ideas and feelings and their progressions won’t be clear until you start organizing them, but once you see them you’ll find new windows into your own work.

With this kind of writing, single words, word pairs, phrases, unfinished sentences, lists, outlines, and mind maps are more effective. Make it personal. Don’t worry about being judged and don’t judge yourself. Forget perfect. Don’t let spelling or grammar or penmanship be an issue; start, flow, and keep moving freely. This is your inner laboratory – and the only way to grant access to yourself is to use words. The goal of this kind of writing is discovery and clarity, not publication. Later, some of the material you gather during this process may ultimately lead to words you can use in conversations, interviews, and statements. Once you make your discoveries, you get to decide what’s better left unsaid … but you can only do that after you’ve found out what you have to say.

When you’re exploring your influences ask yourself a lot of questions. Questions guide exploration. Try these questions …

What is the essence of the influence?

Is it physical?

Is it emotional?

Is it intellectual?

Is it the whole thing or few particular things?

If it’s many things at once, what is the relative weight of each of those things?

Does one influence share elements or qualities with other influences?

… but don’t stop here. Keep going.

At first, it might seem strange to generate a lot of information only to boil it down to a little, but if you try this you’ll find that the insights you’re left with will be more concentrated, help give you more focus, and be easier to act on. Simplicity has many advantages, not the least of which is simple things are easier to remember and easier to share. Never confuse simple-mindedness with simplicity. Simplicity often represents the height of sophistication, arrived at only after practice. If you can present a complex subject in a simple way without sacrificing essential content, you truly understand it.

Consciously consider your influences. You’re choosing what’s most important to you and how best to express that. (Sounds a little like making art.) When you do, you’ll understand and appreciate them better – and your own works too.

Read Why Tracking Your Influences Is So Important here.

Read Ranking Your Influences here.

Find out more about my influences here.

Ways Of Working With Influence

Why Tracking Your Influences Is So Important

The 5 Benefits Of Looking At Other Artist’s Works

State The Nature Of The Influence On You Simply – One Word, Phrase, Sentence

Make A Timeline Of Your Artistic Influences | Coming

How To Deepen Your Relationship With Influences Over Time | Coming

What Was The First Photograph That Ignited Your Passion For Photography? | Coming

What Single Photograph Would You Keep? | Coming

Gather Your Favorite Images Together | Coming

A Combination Of __ & __ | Coming

Why It’s Important To Seek More Influences | Coming

100 Great Photographers To Know | Coming

If You Like ___ Look At ____ | Coming

6 Ways To Map Your Artistic Influences | Coming

The 5 Benefits Of Cultivating Influences Outside Your Medium | Coming

How To Create Something New By Combining Your Influences | Coming

Learning From Negative Influences | Coming

How To Overcome The Fear Of Being Influenced | Coming

How To Make Influences Your Own | Coming

My Influences – Photographic

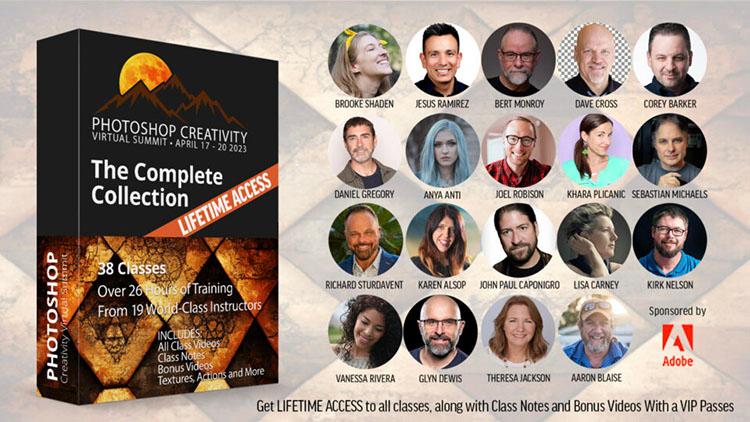

My Top 5 Photographic Influence- Video

Ansel Adams – Empowering Others

Edward Burtynsky – Manufactured Landscapes

Walter Chapelle – More Than Material

Richard Misrach – A Life’s Work

Robert and Shana ParkeHarrison – Environmental Metaphors

Eliot Porter – Environmental Advocacy Through The Arts

Aaron Siskind – Literally Abstract

Jerry Uelsmann – Visions From The Mind’s Eye

Joel-Peter Witkin – Looking Into Darkness

Four Nudes By Four Photographers

Top 20 Photography Books That Influenced Me

My Influences

Mark Rothko – Color As A Universal Language

Matthais Grunewald – Acknowledging The Beatific & The Demonic

Andy Goldsworthy – Ephemeral Collaborations With Nature

Titian inspired Manet

Manet inspired Gaugin

Manet inspired Monet

Van Gogh inspired Hockney

Van Gogh inspired Lichtenstein

Click below to see more and read more.

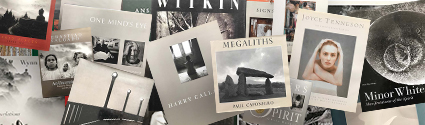

“Enjoy this collection of photographic books that have influenced me during some of my most formative years.

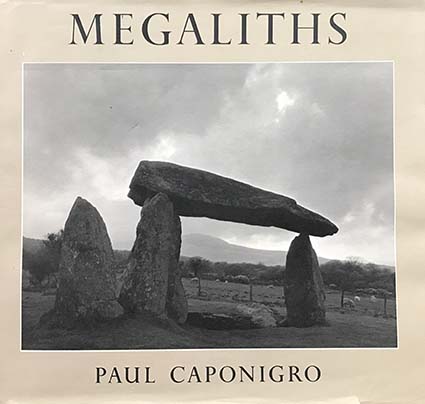

#1

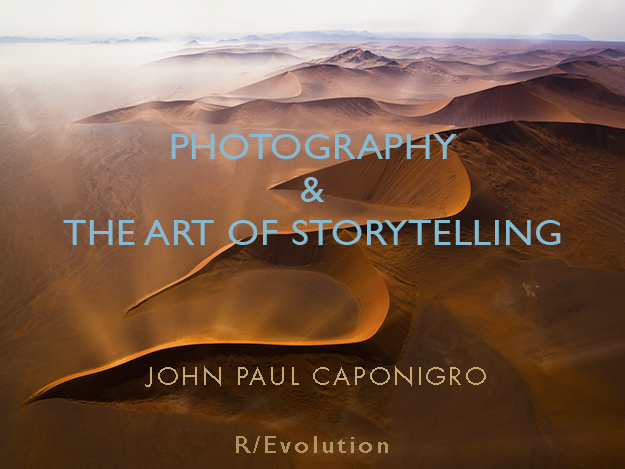

Paul Caponigro – Megaliths

Watching the production of this project from start to finish had a profound effect on me. The book was the culmination of decades of work on so many levels.

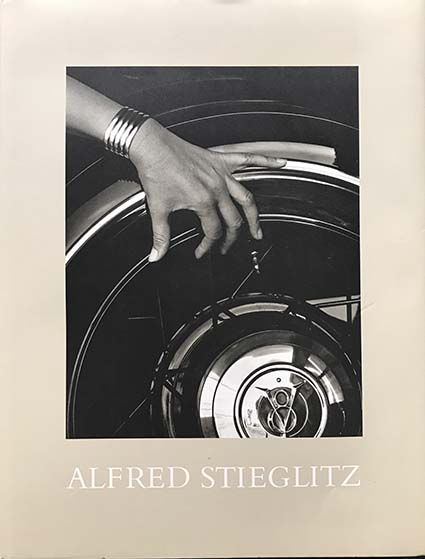

#2

Alfred Stieglitz – Portrait Of Georgia O’Keefe

These portraits and nudes set the highest standards for me. Deep complex emotional connection. The variety of Stieglitz’ printing was eye opening. Meeting O’Keefe was interesting; I still wonder what it was like for her as an older woman to produce a book on her younger self.

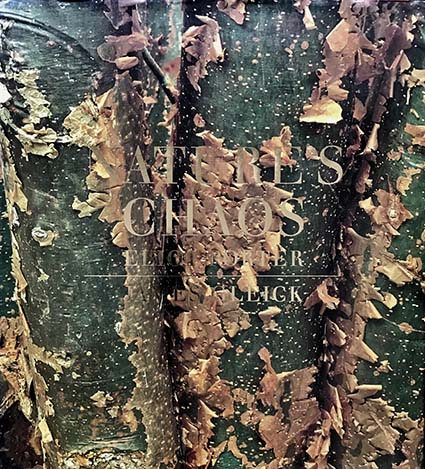

#3

Eliot Porter – Nature’s Chaos

Fortunate to see my mother design many of Porter’s books, this one confirmed my feeling that he saw a deeper order in nature before we more fully understood complexity in the sciences.

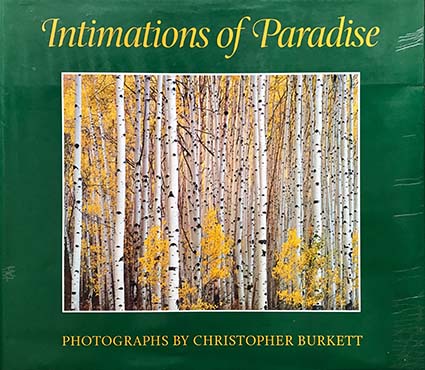

#4

Christopher Burkett – Intimations Of Paradise

Formerly a Gnostic monk, Burkett renounced his vows of poverty so that he could afford film and continue to faithfully transcribe The Book Of Nature. There are so many ways to live life in a sacred way

#5

Edward & Brett Weston – Dune

Dune / Edward Weston And Brett Weston collects works, many never before printed, by father and son showing how similar and how different each artist’s vision was. Working with Kurt Markus to produce this book was eye-opening.

#6

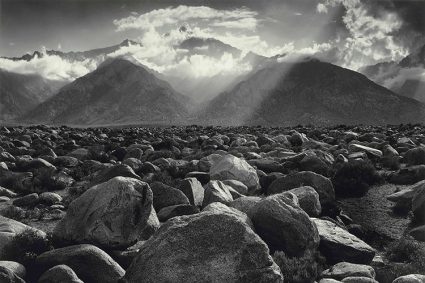

Ansel Adams – The Making Of 40 Photographs

It’s wonderful to read how an artist works and even better to see them in action; I was lucky to do both. I do wish Adams wrote more about why he made each image and what it meant to him.

#7

Jerry Uelsmann – Process & Perception

It demonstrates how process changes perception – and the process you engage is a personal choice. The inside is just as important as the outside.

#7

Edward Burtynsky – Manufactured Landscapes

While Eliot Porter didn’t want to beautify trash through art Burtynsky turns an unflinching eye towards industrial impacts on land crafting a complex statement on land use and ultimately identity.

#8

Minor White – Manifestations Of The Spirit

No other photographer is as articulate about the inner experience of making art. His essay on equivalence is seminal.

#9

Wynn Bullock – Revelations

Bullock’s marriage of science/physics and art

became as much a philosophical statement as a celebration of beauty.

#10

Kenro Izu – Sacred Places

Izu tries to photograph the spirit of ancient sacred places. When he talks about atmosphere he means more than weather.

#11

Chris Rainier – Keepers Of The Spirit

If Edward Curtis met Joseph Campbell you’d get Rainier’s survey of spirituality in world cultures.

#12

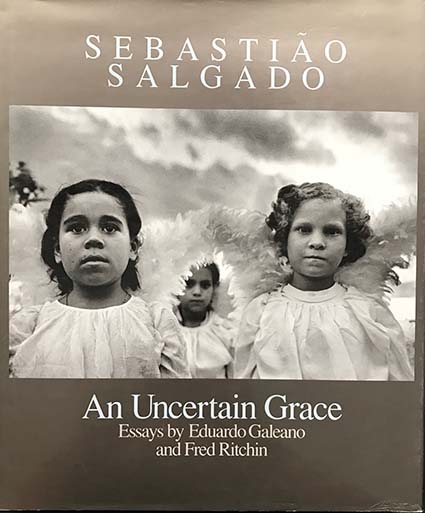

Sebastiao Salgado – An Uncertain Grace

Salgado sets the bar high by bringing out the dignity within his subjects no matter how undignified their circumstances.

#13

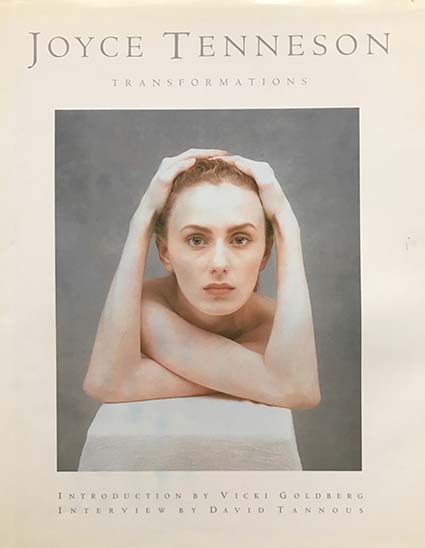

Joyce Tenneson – Transformations

Tenneson’s images remind me of what Pierre Teilhard de Chardin said, “We are not human beings having a spiritual experience; we are spiritual beings having a human experience.”

#14

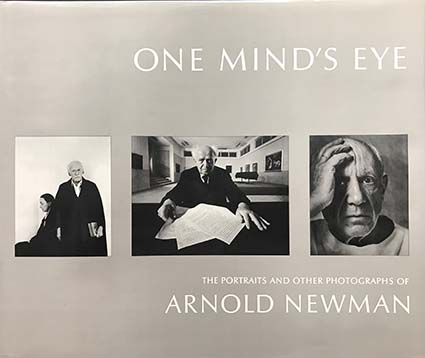

Arnold Newman – One Mind’s Eye

Beautifully constructed portraits from the father of environmental portraiture.

#15

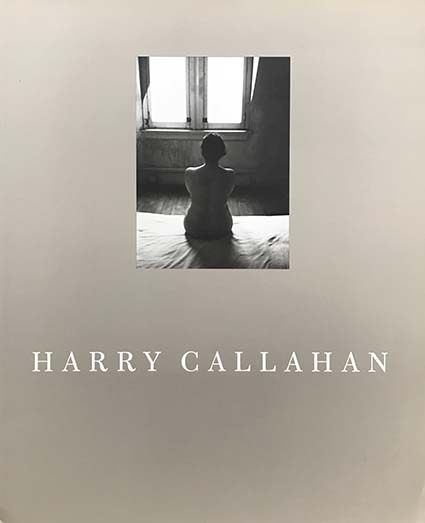

Harry Callahan

The rest of his wrestlessly inventive work intrigued me but his deeply honest extended portrait of his wife set a standard I hope for in all others.

#16

Sugimoto

It’s minimalism that isnt shallow or evasive; the collection reinforces the concept, creating a context for itself. It asks so many questions? Enough? Not enough? Do all the world’s oceans look the same? Or is it just one ocean? Is it the camera or the artist who makes them look the same? Is it the way we look? How is it that by looking at them long enough I begin to see myself?

#17

Richard Misrach – The Sky Book

Pleasant as it is this minimalism ordinarily wouldn’t be enough for me. But then he adds the titles of time and places in many languages with a history. Together they grow stronger and placed within his life work as one of many Desert Cantos they grow stringer still. Rebecca Solnit’s accompanying essay is excellent. I learned a lot from looking at this – about art and myself.

#18

Witkin

I find Joel Peter Witkin’s work profoundly challenging. I can’t say I love it; I can’t say I hate it. I can say it continually crosses back and forth between self-indulgently expressing his individual perversions and courageously looking unflinchingly into a universal heart of darkness.

#19

Michael Kenna – Night Work

Kenna’s elegant minimalism is laced with a quiet spirituality that comes less from tradition and more from being in the moment, growing most emotional when he’s in the dark.

#20

Huntington Witherill – Orchestrating Icons

It’s musical for its flowing compositions and exquisite tonalities. Extraordinary separation in extreme highlights and shadows, no one prints quite like him in.

Find out more about my influences here.

Here’s a selection of my favorite quotes on influence.

“People exercise an unconscious selection in being influenced.” – T. S. Eliot

“To be realistic one must always admit the influence of those who have gone before.” – Charles Eames

“The superior artist is the one who knows how to be influenced.” – Clement Greenberg

“Every art, like our own, has in its composition fluctuating as well as fixed principles. It is an attentive inquiry into their difference that will enable us to determine how far we are influenced by custom and habit, and what is fixed in the nature of things.” – Sir Joshua Reynolds

“A young painter who cannot liberate himself from the influence of past generations is digging his own grave.” – Henri Matisse

“Picasso once remarked, ‘I do not care who it is that has or does influence me as long as it is not myself.’” – Gertrude Stein

“I am not influenced by the techniques or fashions of any other motion picture company.” – Walt Disney

“I don’t believe in learning from other people’s pictures. I think you should learn from your own interior vision of things and discover, as I say, innocently, as though there had never been anybody.” – Orson Welles

“The only real influence I’ve ever had was myself.” – Edward Hopper

“Add new painters to your list of favorites all the time.” – Irwin Greenberg

“We are shaped and fashioned by what we love.” – Goethe

“The strongest influences in my life and my work are always whomever I love. Whomever I love and am with most of the time, or whomever I remember most vividly. I think that’s true of everyone, don’t you?” – Tennessee Williams

“We don’t make a photograph just with a camera, we bring to the act of photography all the books we have read, the movies we have seen, the music we have heard, the people we have loved.” – Ansel Adams

“There are so many moments and works that influence us in what we do. Movies, music, TV and, most importantly, the profound everydayness of our lives.” – Barbara Kruger

“The influences may be subliminal and subtle but all that surrounds us in some way changes how we see things and who we are.” – Martine Gourbault

“Movies can and do have tremendous influence in shaping young lives in the realm of entertainment towards the ideals and objectives of normal adulthood.” – Walt Disney

“Advertising reflects the mores of society, but it does not influence them.” – David Ogilvy

“The only books that influence us are those for which we are ready, and which have gone a little farther down our particular path than we have yet got ourselves.” – E. M. Forster

“I have been influenced by paintings I have seen in books, and in museums, not because they defined success but because they suggested possibilities.” – Eleanor Blair

“There is a boundary to men’s passions when they act from feelings; but none when they are under the influence of imagination.” – Edmund Burke

“Every thought which genius and piety throw into the world alters the world.” – Ralph Waldo Emerson

“Ideas are the mightiest influence on earth. One great thought breathed into a man may regenerate him.” – William Ellery Channing

“The influential man is the successful man, whether he be rich or poor.” – Orison Swett Marden

“When it comes to developing character strength, inner security and unique personal and interpersonal talents and skills in a child, no institution can or ever will compare with, or effectively substitute for, the home’s potential for positive influence.” – Stephen Covey

“The humblest individual exerts some influence, either for good or evil, upon others.” – Henry Ward Beecher

“You don’t have to be a ‘person of influence’ to be influential. In fact, the most influential people in my life are probably not even aware of the things they’ve taught me.” – Scott Adams

“There is no pebble so small that it won’t make ripples when tossed into a body of water.” – Charles Peck

“Any one of us can be a rainbow in somebody’s clouds.” – Maya Angelou

“And as we let our own light shine we unconsciously give other people the permission to do the same.” – Marianne Williamson

“Think twice before you speak, because your words and influence will plant the seed of either success or failure in the mind of another.” – Napoleon Hill

“It takes tremendous discipline to control the influence, the power you have over other people’s lives.” – Clint Eastwood

“A teacher affects eternity; he can never tell where his influence stops.” – Henry Adams

“The influence of each human being on others in this life is a kind of immortality.” – Winston Churchill

“Be around the people you want to be like, because you will be like the people you are around.” – Sean Reichle

“Be around people who have something of value to share with you. Their impact will continue to have a significant influence.” – Jim Rohn

“We never know which lives we influence, or when, or why.” ― Stephen King

“It would be difficult to exaggerate the degree to which we are influenced by those we influence.” – Eric Hoffer

“Influence is to be measured, not by the extent of surface it covers, but by its kind.” – William Ellery Channing

“The most powerful moral influence is example.” – Huston Smith

“Example is not the main thing in influencing others. It is the only thing.” – Albert Schweitzer

“Setting an example is not the main means of influencing another, it is the only means.” – Albert Einstein

“There is no influence like the influence of habit.” – Gilbert Parker

“Affluence means influence.” – Jack London

“A return to first principles in a republic is sometimes caused by the simple virtues of one man. His good example has such an influence that the good men strive to imitate him, and the wicked are ashamed to lead a life so contrary to his example.” – Niccolo Machiavelli

“Neither a man nor a crowd nor a nation can be trusted to act humanely or to think sanely under the influence of a great fear.” – Bertrand Russell

“In the councils of government, we must guard against the acquisition of unwarranted influence, whether sought or unsought, by the military-industrial complex. The potential for the disastrous rise of misplaced power exists and will persist.” – Dwight D. Eisenhower

“The time has come for all evangelists to practice full financial disclosure. The world is watching how we walk and how we talk. We must have the highest standards of morality, ethics and integrity if we are to continue to have influence.” – Billy Graham

“The most hateful human misfortune is for a wise man to have no influence.” – Herodotus

“I hold that a strongly marked personality can influence descendants for generations.” ― Beatrix Potter

“The purpose of influence is to “speak up for those who have no influence.” ― Rick Warren

“Once you’ve found your own voice, the choice to expand your influence, to increase your contribution, is the choice to inspire others to find their voice. Inspire (from the Latin inspirare) means to breathe life into another. As we recognize, respect and create ways for others to give voice to all four parts of their nature–physically, mentally, emotionally/socially, spiritually–latent human genius, creativity, passion, talent and motivation are unleashed. It will be those organizations that reach a critical mass of people and teams expressing their full voice that will achieve next-level breakthrough in productivity, innovation and leadership in the market place and society.” – Stephen Covey

Read more Creativity Quotes here.

View more Creativity Videos here.

Suffusion I, Palm Beach, Florida 2001

Sometimes ideas just seem to come out of nowhere. But do they?

We have so many experiences everyday, whether commonplace and routine or extraordinary and novel, it’s hard to say what registers as significant or even important. We’re influenced by so many things – our history, environment, community, actions, etc – that it’s hard to know when one thing leads to another. Often we refashion these materials, sometimes combining them, into something new, so when the resurface it’s not easy to recognize where they came from. What do we connect with? When do we connect with it? Do we know when it happens? Only if we’re mindful.

Awareness of what influences us is something that we can develop. To do this we need to develop a greater sensitivity to our environment and history in it (both personal and cultural) as well as to our actions and attitudes in relation to the activities and tone of our communities. Inquisitiveness is all you need. Ask a lot of questions. Don’t assume you know the answers. Don’t judge yourself or the answers you find along the way. Just collect information. By becoming aware of your influences you’ll be less controlled by them, see more options, and so have more and make clearer choices. Journalling can be an excellent way to develop this discipline and to reflect further on your influences while you’re making new or reviewing old entries. Once you experience the many benefits awareness of your influences brings, you’ll want to cultivate this habit. It can be a source of clarity, of personal insight, and even of purpose. Time and time again, this has been true for me.

Sometimes the insights awareness brings are surprising. One day, after Suffusion I had been hanging on my studio wall for months, I moved a snapshot of my grandmother’s ashes in the ocean (I had been unable to attend her funeral so I kept the photograph my father brought me close for a time.) across my studio. As soon as I saw the two images simultaneously in my field of vision the similarities and connections between them became clear. Since I made it, I had been trying to understand Suffusion I better. I knew some of the undercurrents at work in it; growing concerns about climate change and global warming; the ever-changing nature of existence and perception; watching smoke as a form of meditation; using smoke as a form of prayer. But I hadn’t guessed that it had anything to do with death and cremation. It would be a mistake to say this image – and the other images like it in this series – was about death. It/they are about much, much more. That’s part of what makes them so good. They’re complex.

You might be tempted to say that the influences were simple. The environmental and temporal factors were obvious. A good friend (Timothy Morrissey) had shown me how he photographed smoke and mist in his studio and I made exposures with him. The next day we went fishing and I made more exposures. Much later, I combined images from the two days. But that wouldn’t have explained why I chose to do this; I could have chosen one of thousands of other exposures from other years. Nor would that explain that I liked the results enough to print, frame, and exhibit the results. There was more going on in this image than first met the eye. I knew this, which is why I was still curious about it – and it probably has something to do with why others are curious about it too. I’m still curious. Our best work gets ahead of us and it takes time to catch up to it. Sometimes it continues to reward us for years to come – or even a lifetime.

Questions

How many things influence you?

How many things can you do to increase your awareness of what influences you?

What are the best ways to track your influences?

What benefits do you find from looking back on how your influences develop, flow, and grow?

Can you use the insights about your past reactions to inspire new actions?

How many ways can you proactively influence your influences?

Find out more about this image here.

View more related images here.

Read more The Stories Behind The Images here.

Read more about Influences here.