Photographer Sarah Leen – Her Top 5 Influences

“Who are your influences?” It’s a question often asked by professors to help artists grow, critics to place artists’ work and ideas in context, and audiences to understand artists’ creations. It’s also a question we can ask to do all of these things for ourselves.

Track It Like A Hunter

When you have a realization, write it down. Writing not only creates a durable record you can refer to later, it also makes it far more likely that you will remember what you write. List all of your influences in one place, and you’ll see connections between your influences by making comparisons and contrasts –sometimes, finding these insights requires asking follow-up questions like, “How do the relationships between these things indicate shared qualities and themes within my own work?” and “How can the difference between these things be used to create something new?” Date the times you are influenced, and you’ll see how chain reactions of thoughts and feelings start, grow, and change. You can expand your understanding by writing more than lists. Write a simple line stating the essence of what the work means to you. You may find this process so rewarding that you write more in a short paragraph or two or three that will help you reveal more connections to other feelings, thoughts, and things to clarify the essence of your response, which you may repurpose in your own artist’s statements.

Sometimes, an influence, rather than coming from another artist’s entire body of work, comes from a single piece, perhaps even an atypical work. Sometimes, an influence comes from an artist working in a seemingly unrelated discipline. Sometimes, an influence comes from something we don’t like or resist. Of course, many other things influence us besides other artists’ works and are worth tracking, too.

Progress From What To How To Why

It’s one thing to list our artistic influences; it’s another to clarify how we are responding or what they mean to us. Moving beyond questions of what influences us to how and why they influence us deepens our understanding and connection to the things we are moved by. It only takes a sentence or two, maybe only a few phrases or even a single word, to find insights that move us in new directions or propel us to new heights.

Be Mindful

Being self-aware is different than being self-conscious. During this process, silence your inner critic. The voice(s) that helps you evaluate ideas or results is not the same voice that sees new possibilities and generates ideas. This critical aspect of ourselves can be very helpful, selecting and refining, and strengthening the best ideas drawn from many, but it serves us best after a process of observation and generation, if it is active during those processes, it can stop the flow of thoughts and feelings. Here, don’t judge; just watch.

Observing our inner world, our thoughts and feelings, our associations and disassociations, our fixations and aversions, and their interconnections move rich material from the dark corners of our subconscious into the light of the conscious mind. If we do this, we can find more material to work with, we can ask generative questions to help us grow, we can make clearer/better choices, and it’s very likely that we will be more productive and more fulfilled. When awareness is present, our artistic process becomes a journey of personal discovery, which is sometimes challenging but always rewarding.

Ways Of Working With Influence

Why Tracking Your Influences Is So Important

The 5 Benefits Of Looking At Other Artist’s Works

State The Nature Of The Influence On You Simply – One Word, Phrase, Sentence

Make A Timeline Of Your Artistic Influences | Coming

How To Deepen Your Relationship With Influences Over Time | Coming

What Was The First Photograph That Ignited Your Passion For Photography? | Coming

What Single Photograph Would You Keep? | Coming

Gather Your Favorite Images Together | Coming

A Combination Of __ & __ | Coming

Why It’s Important To Seek More Influences | Coming

100 Great Photographers To Know | Coming

If You Like ___ Look At ____ | Coming

6 Ways To Map Your Artistic Influences | Coming

The 5 Benefits Of Cultivating Influences Outside Your Medium | Coming

How To Create Something New By Combining Your Influences | Coming

Learning From Negative Influences | Coming

How To Overcome The Fear Of Being Influenced | Coming

How To Make Influences Your Own | Coming

My Influences – Photographic

My Top 5 Photographic Influence- Video

Ansel Adams – Empowering Others

Edward Burtynsky – Manufactured Landscapes

Walter Chapelle – More Than Material

Richard Misrach – A Life’s Work

Robert and Shana ParkeHarrison – Environmental Metaphors

Eliot Porter – Environmental Advocacy Through The Arts

Aaron Siskind – Literally Abstract

Jerry Uelsmann – Visions From The Mind’s Eye

Joel-Peter Witkin – Looking Into Darkness

Four Nudes By Four Photographers

Top 20 Photography Books That Influenced Me

My Influences

Mark Rothko – Color As A Universal Language

Matthais Grunewald – Acknowledging The Beatific & The Demonic

Andy Goldsworthy – Ephemeral Collaborations With Nature

Alfred Stieglitz’ extended portrait of Georgia O’Keeffe is a penetratingly honest act of love.

Christopher Burkett’s makes accurate representation an extension of his spirituality; he celebrates Creation by faithfully transcribing “The Book Of Nature”.

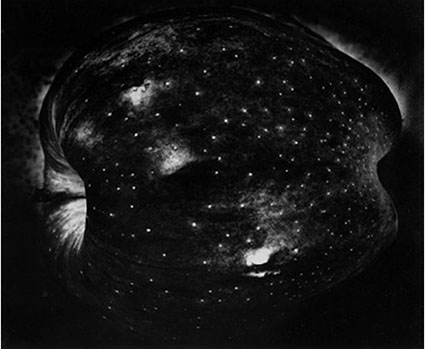

Paul Caponigro’s “Galaxy Apple” reveals a macrocosm within a microcosm, demonstrating the power of metaphor; ordinary things are seen as extraordinary.

Eliot Porter’s photography intuited more complex realtionships in nature before the field of chaos science was popularized.

Pollution or blood? A tense mystery is created by Edward Burtyinsky’s beautiful images of distressed landscapes.

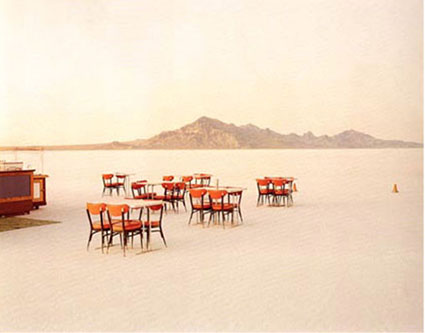

Richard Misrach’s Desert Cantos examines a single subject (the American desert southwest) in many different ways over a long period of time, creating a dense web of interconnections.

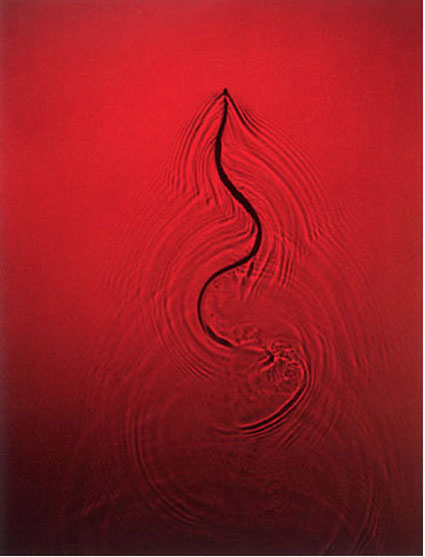

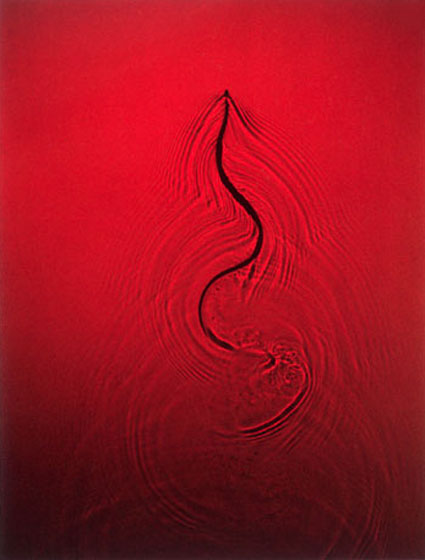

Adam Fuss’ photograms, as much about shadow as light, share a stance similar to many abstract painters who point to the object created more than what it refers, while at the same time highlighting the distortions that lenses can bring to representation. The questions his work raise are generative.

Walter Chappelle’s Metaflora series creates images with plants, electricity, and photosensitive paper in complete darkness. What else can’t we see? What would we see if we could?

Jerry Uelsmann bring’s images in the mind’s eye into sharp focus with the most directly representational medium.

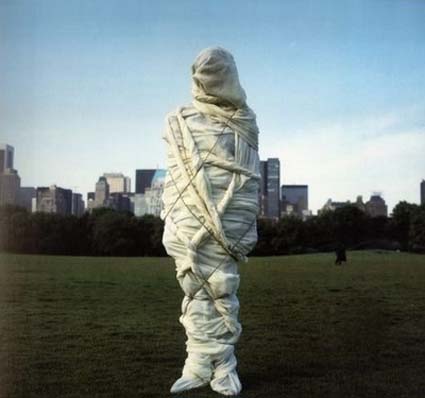

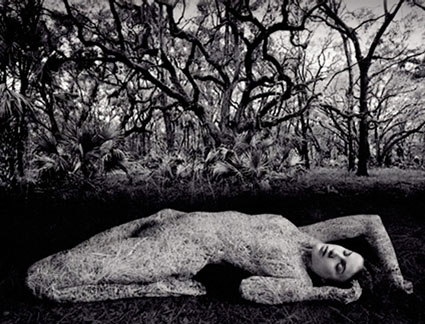

Robert and Shana Parke-Harrison’s post-apocalyptic poems perform acts of care for the natural world despite their odds of success.

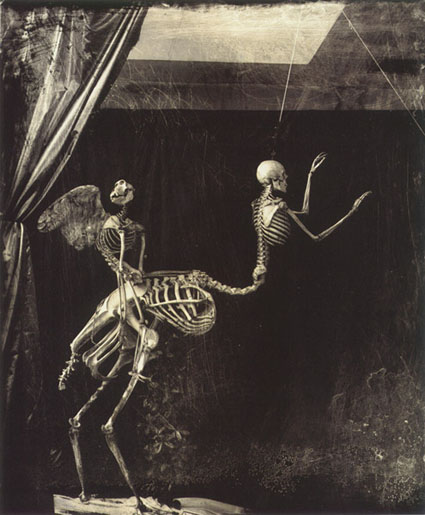

Courageous and honest or perverse and self-indulgent? The complex mix of beauty and taboo, infused with death and sexuality, and guilded with art historical references and fine craft is extremely provocative. It’s honest but is it Truthful? Is it wise?

Andy Goldsworthy’s photographs are all most of us see of his ephemeral earth works often made in remote locations. So what’s the real art? The performance? The object created? The photographic record? The books that collects those records? All of it?

………………..

Photographers look at and understand photographs differently than the average viewer. Their years of unique personal experience with the medium is special. For me, their insights open new windows into the medium, the world, and myself. I hope they do the same for you.

In this series of posts, each photographer selects 12 if their favorite photographs and provides a short insight into why these images are so moving to them.

I’m kicking off a series of photographer’s celebrating photographs.

View more Photographers Celebrate Photography here.

Stay tuned for upcoming additions.

View 12 Great Photographs By John Paul Caponigro here.

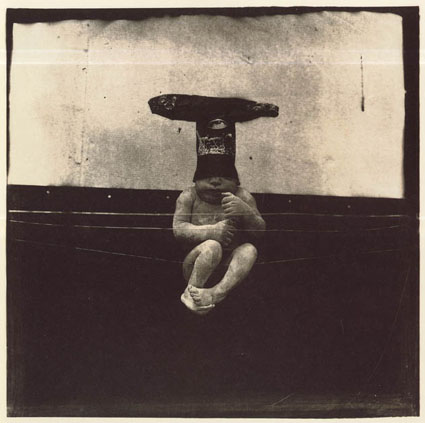

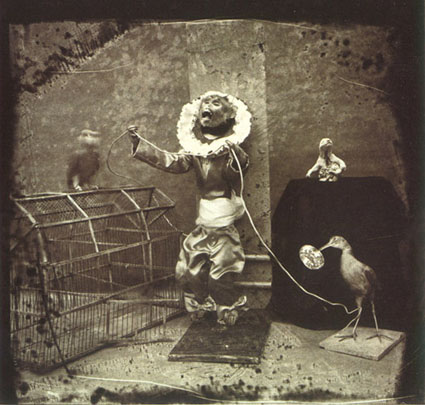

I find Joel-Peter Witkin’s photography supremely challenging. It would be easy to write his work off as sensational (His images are so shocking they make headlines.), perverse (His models are, if alive, unusual body types including dwarves and hermaphrodites, if dead, cadavers, amputations, skeletons, and carrion, while his props often include sado-masochistic paraphernalia and torture devices.), and contrived (He reproduces historic masterworks in his own dark way.). But that would be too easy.

Witkin’s work challenges me to look at things I turn away from and my own denial. There’s an unusual beauty in his work. This beauty is drawn from much more than exceptional print quality, which though chaotically distressed and painted is nonetheless crafted masterfully. In his best work Witkin transcends the fleeting beauty found on the surfaces of things and penetrates deeper to find a more enduring beauty that lies below the surface – in the most unexpected places and sometimes in the most unexpected ways. I think it takes wisdom to see beauty (especially unconventional beauty) and that beauty imparts wisdom.

Witkin doesn’t consider the things he’s photographing taboo or ugly. He claims to simply acknowledge their existence and to have found beauty within them. Thus he doesn’t think his work aestheticizes negativity, perversion, or violence. For this to be absolutely true he would need the unerring powers of a saint. Sometimes he misses the mark, either from aiming at the wrong target, a misdirection born out of a calculation designed to impress rather than a passion designed to transform, or from not penetrating deeply enough, perhaps he is not as unflinching as he would lead us to believe. But, he is always courageous and dares to explore in depth what few ever dare to glimpse.

The true task of looking at Witkin’s work is found in differentiating which of Witkin’s images transcends cleverness – not all of them do – to achieve true insight – those that do offer a most unusual substance. The true reward of looking at Witkin’s work is … The shock his best work produces is not the kind of shock that quickly passes leaving me looking for the next big rush. The shock his best work produces haunts me long after I’ve seen his work, sometimes never passing. Appreciating Witkin’s images leaves me more aware, perhaps more alive, potentially wiser, and never unchanged.

Witkin challenges me to flinch less, or if I flinch, to find the courage to continue looking and moving forward. He reminds me that the apprehension of beauty and the wisdom derived from it is made stronger by acknowledging and perhaps coming to a better understanding of the darker aspects of existence.

Find out more about my influences here.

The following images contain nudity. The choice to continue looking is yours.

Read More

Adam Fuss’ photograms encourage you to think about photography, in different ways and much more broadly. His life-sized camera-less photograms represent one man’s attempt to work with, explore, and see subjects, media, and perception more directly. By making camera-less images, Fuss eliminates many distortions inherent in optical systems that employ lenses.

The turning point in Adam Fuss’ work came when he accidentally processed a piece of film that recorded only a grain of dust and its shadow. He had the sensitivity to see something extraordinary in this ordinary moment. Since then, he’s explored many ways of making photograms, including producing images from the chemical reactions created by photosensitive materials coming in contact with viscera and decaying objects.

Fuss’ photograms highlight the idea of the photograph as a trace made by light that has come in direct contact with the thing recorded. Fuss takes this one step further in his photograms, as the objects, not just the light reflected from them, literally make contact with the recording device, which becomes the final art object. Akin to abstract painting, the thing made represents itself more than the subject.

In Fuss’ work, the absence of light reveals as much or more as the presence of light, reversing our conventional expectations of photographs (‘light drawings). This is more than just ironic – it’s insightful.

Like Plato’s The Allegory Of The Cave, where men raised in a cave are bound in such a way that they only see shadows and mistake them for the real things not just reflections of reality, Fuss’ photograms ask us to consider the limited nature of our perceptions and not to confuse the recordings we make with the things themselves.

Read my extended conversation with Adam Fuss here.

Find out more about my influences here.

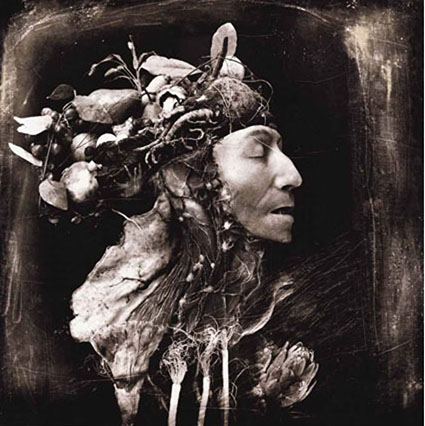

Walter Chapelle’s Metaflora series is the kind of photography that fascinates me most. Rather than portraying things as we see them, it uses photography to extend our senses, providing new windows into the universe.

Chapelle uses Kirlian photography to look deeply into the world of plants. Kirlian photography (named after the Russian inventor Semyon Kirlian) is a form of camera-less form of photography, akin to a photogram, that records the effects of high voltages of electricity applied to objects in contact with light-sensitive material. An electric current separates the electrons from atoms and objects become ionized and glow, albeit faintly. Typically, nothing is seen by the observer during exposure, but an image appears when developed. The size and shape of the energy field are related to the amount of water, a prerequisite for life, in the object as well as the surrounding atmosphere. Plantlife loses moisture after it is harvested so the length of time between picking and exposure affects the intensity of the effect. Electromagnetic radiation penetrates beyond the typically opaque surfaces revealed by reflected light, itself one manifestation of a broader spectrum of electromagnetic radiation, and renders both the interiors and the immediate exteriors surrounding objects.

This glimpse into the invisible electro-magnetic fields that surround all objects, including our own bodies, generates visual effects that are reminiscent of the age-old idea of auras or the spiritual bodies of living things. Part science and part poetry, Chapelle uses this unusual perspective to speak metaphorically about seeing into the hidden dimensions of ourselves.

Andy Goldsworthy considers his sculptures collaborations with nature.

It’s Goldsworthy’s pieces that don’t persist that impress me most. Why? It’s not because they reverse traditional expectations, that through art an individual and culture achieves extended longevity if not immortality. It’s because Goldsworthy is free to interact with and interpret the landscape without removing this possibility for us. In many ways, his work is an invitation for all of us to participate with land in a similar spirit on our own terms.

I appreciate the irony that a majority of us see most of his work through photographs. In this respect an argument can be made that his primary medium is photography. Even if we have had direct experience with his work, our photographic experience of his work is more persistent. Over time, does the second-hand experience supersede the primary one? He’s managed to use two mediums to complement and comment on each other, while shedding light on our relationships to land and our own identities.

All of these are sentiments I resonate with strongly. What’s more, I might have framed my self-identity more narrowly as a photographer only were it not for the inspiration of artists like Andy Goldsworthy.

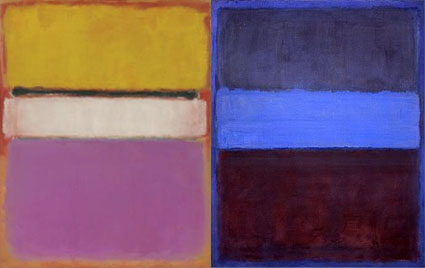

Sometimes the things we resist influence us the most. For me, this was certainly the case with the paintings of Mark Rothko.

As a young man, I found myself alienated from many modernist works. I felt they were overly intellectual; you needed a degree to begin to approach them much less understand them. They didn’t meet the audience halfway. Some of them even needed critical interpretation to be fully resolved.

Nonetheless, my intensely emotional reactions to Mark Rothko’s paintings were undeniable. Standing before these fields of color produced a physical sensation, much like listening to music. Rothko was able to communicate powerful emotions with the simplest means. Often his canvases were composed no more than two rectangles inside the larger rectangular field of the canvas or as few as three colors. Unlike DeKooning, gesture isn’t what communicates emotion – Rothko’s canvases are stained. Rothko’s use of scale, quite different than Albers’, also impressed me; the large fields immerse you in the sensation of color, further intensifying it.

Rothko’s painting was more than an exploration of optics, it was also a spiritual quest. It’s not just color for color’s sake; it’s color placed in the service of the human spirit. Upon further study, I found that many early modernists shared a similar spiritual impulse and used abstraction in a quest for a universal language that reached beyond time and culture. For me this was the link between the modernists I appreciated and the ones that left me cold. It was a quest I resonated with. It started a chain reaction within my thinking about and appreciation of art. I continue to search for similar qualities in my own work.