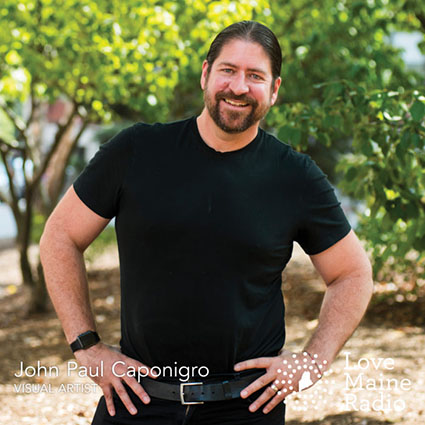

Unlocking The Secrets Of The Creative Process – A Conversation Between Eric Meola & John Paul Caponigro

August, 2017

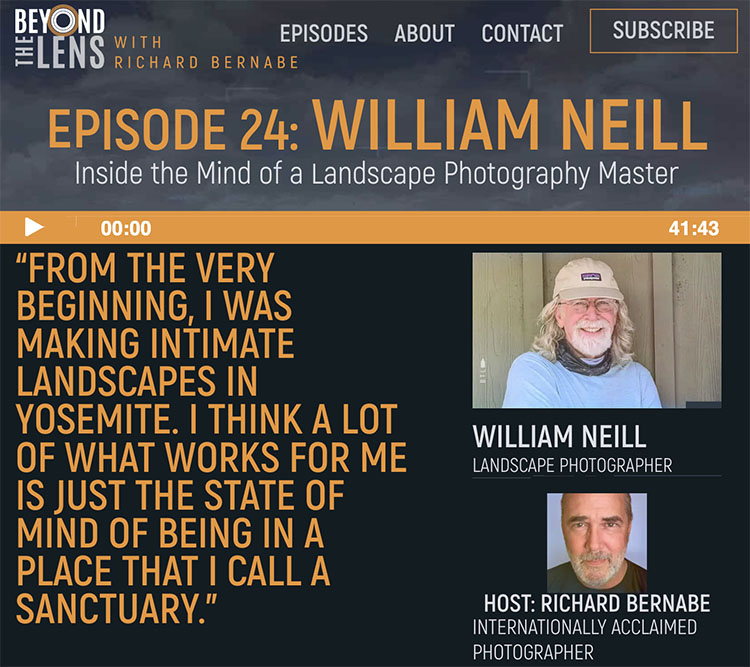

Eric Meola

What is the process of creativity? Where does it come from, and how does it evolve? Recently, photographer and PPD contributor Eric Meola raised those questions in an interview with photographer and educator John Paul Caponigro, whose work will soon be featured along with his father’s in a major new exhibition at the Taubman Museum in Roanoke VA, “Paul Caponigro and John Paul Caponigro: Generations.” Today we publish part one of the interview, in which Caponigro and Meola talk about chaos, self-doubt, reflection, serendipity, failure, discipline, and the myriad facets of interaction that lead to creativity and art. Look for the rest of the interview in upcoming editions of PPD.

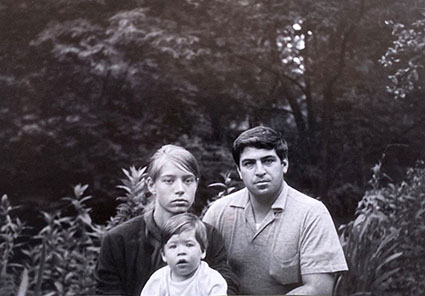

At a recent workshop in Maine, the noted National Geographic photographer Sam Abell asked his students to photograph a poem—to illustrate the words with images. Abell wanted the students to think about the relationship between two methods of describing imagery, and the challenges posed by interpreting words and images in our minds through photography. The dichotomy between words and images has haunted me throughout my career, and then a few months ago, a nearly 200-page PDF attachment of an e-book called Process arrived in my email as a gift from photographer-lecturer-educator John Paul Caponigro —or JP, as his friends call him. I glanced at a few pages, then put it aside on my computer’s desktop to look at later. I had met JP on several occasions—first in California before we were both scheduled to do lectures, and then again in Iceland, Antarctica, and the Atacama desert while participating in Digital Photo Destinations workshops (www.digitalphotodestinations.com). I had only a few sketchy things to go on—that JP had graduated from Yale, that his father was the photographer Paul Caponigro, that he had grown up in New Mexico, and that he took a few weeks off to go to Italy every year.

So one day, when I got a call from my somewhat inebriated photographer-friend Arthur Meyerson and an equally inebriated JP as they joyfully celebrated the close of a Maine Photo Workshop, I told JP that I had not only read Process but that I wanted to interview him about it. I had a lot of questions: How was his famous father? Did his mother really design Ernst Haas’s book The Creation? And most importantly, what the hell was Process really about? After all, we live in the age of iPhone photography, when nearly 300 million photographs are uploaded to Facebook every 24 hours.

In the book Invisible Republic: Bob Dylan’s Basement Tapes, critic Greil Marcus describes the process that led to Dylan’s collection of more than 100 mostly unreleased songs; the music evolved from—in Marcus’s words—“a laboratory where, for a few months, certain bedrock strains of American cultural language were retrieved and reinvented.” Few photography workshops explore the creative aspects of photography as a constantly evolving set of inputs—reading, writing, sketching—that manifest themselves in the way we make images. I recognized that many of my inputs had much in common with what JP was discussing, but I wanted to know more about him and why he always seemed to be “looking away” from the image in front of us. Or was he?

Our conversation, which begins below, took place over an extended period via email, while JP was with his family in Italy.

EM: I’m fascinated by your approach to seeing, to “living” photography, which you refer to as “process.”

JP: Art arises out of a life lived—it’s an extension of ourselves, our creative process grows and changes as we do. Art is not something separate from life. Art intensifies life. Some cultures don’t have a word for art, considering the items/events produced that we might call art to be an overflowing of life. Seen from that perspective, everyone is an artist. So the follow-up questions would be: What kind of artist and how well do they do it?

EM: Your father is Paul Caponigro, a master landscape and still-life photographer. He once said, “It’s one thing to make a picture of what a person looks like; it’s another thing to make a portrait of who they are.” That applies to all photography, doesn’t it—from landscapes to journalistic images to portraits?

JP: Exactly. Representation is not reproduction. We make portraits of people by recording light reflecting on their bodies—often only a portion of their bodies, usually from one angle and at one moment in time. Does such an image record their changing state through time, their history, their web of relationships, their ideas, their feelings, etc? It’s important to recognize the limited nature of our creations. In representation. it’s important to recognize the gap between what we create and what’s referenced. This doesn’t make these types of images less valuable; for many people they’re the most valuable. Perhaps those limitations can be used for effect?