10 Benefits Of Building Bodies Of Work

“There’s nothing worse than a sharp picture of a fuzzy concept.” – Ansel Adams

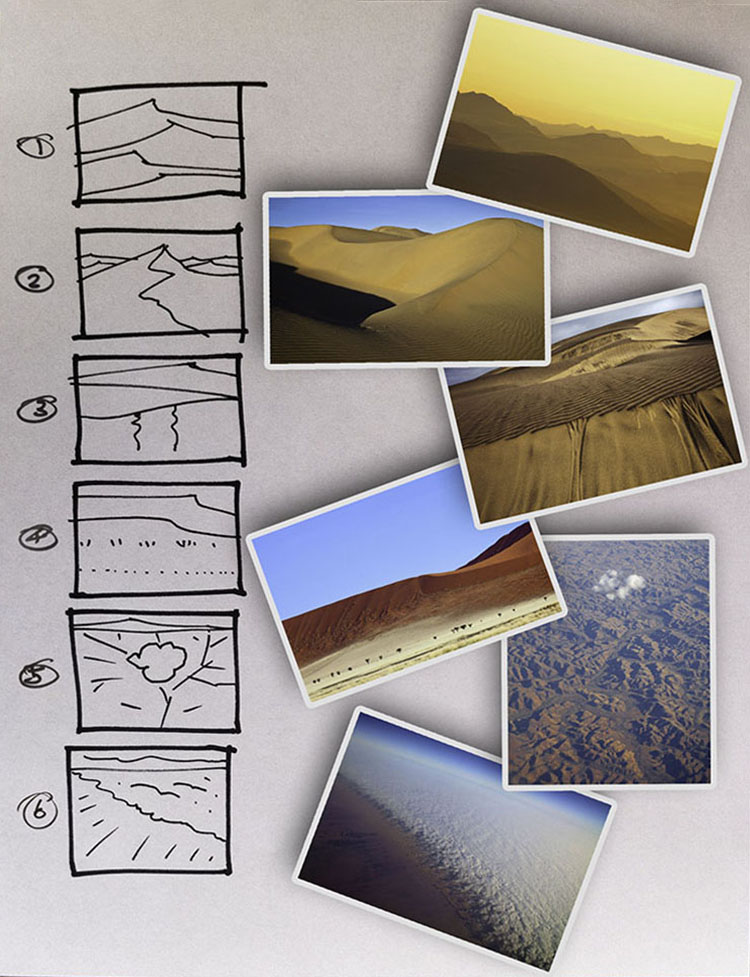

One image is an idea. A body of work is a way of thinking. A collection of singular (5-star) images doesn't create a body of work. Singular images prove your craft. A body of work proves your artistry.

Benefits Of Working In Series

The benefits of developing projects are many. When you learn to present your images as a focused series rather than a random collection of photographs, you'll feel more fulfilled and be more accomplished, developing a deeper sense of your goals, vision, and style. You'll be able to share your images with others more meaningfully and memorably, increasing the chances of publication, exhibition, sales, and collection.

More Images Make Images More Useful

How many images does it take to create a body of work? At least twelve. Think of what you can do with a number of images. 12 or more images can fill a portfolio box or an exhibition space. 12+ images can make an exhibition and/or fill a portfolio box. 24+ images can make a catalog. 36+ images can make a book. Thinking about these outcomes before you begin to shoot can be useful.

Less Is More

You want each body of work to be as strong as possible. Clarify the signal. Eliminate the static. It's better to present just 12 strong images than to bury those same 12 images amid a flood of weaker images. In any body of work, maintain a high percentage of your highest quality work (4 and 5-star images). This is particularly true of small bodies of work. With so few players to state, develop, and conclude a theme, you've got to make every one count.

While weak work weakens strong work, less obvious smart or strongly felt work strengthens it. Images that don't represent your highest quality but still have integrity (3-star images) can be very useful for adding complexity, nuance, and context. Don't overlook these kinds of images, but limit them. Pockets of weaker images create eddies and lulls that can dilute or divert the flow of the main idea. Too many become distracting. To avoid this, punctuate or surround them with stronger images.

One of the benefits of developing a body of work is that you make relative comparisons between many of your images, learning which of your images are stronger or more interesting, what makes them that way, and how to make more in the future.

Theme

What separates a few great images with style (how you say what you say) from a body of work is vision (what you have to say), which gives style purpose. (See The Differences Between Vision & Style.) You'll find out what your voice (vision and style combined) is when you develop a body of work as it reveals your themes (enduring preoccupations). When you develop your themes, you go further and dig deeper. >