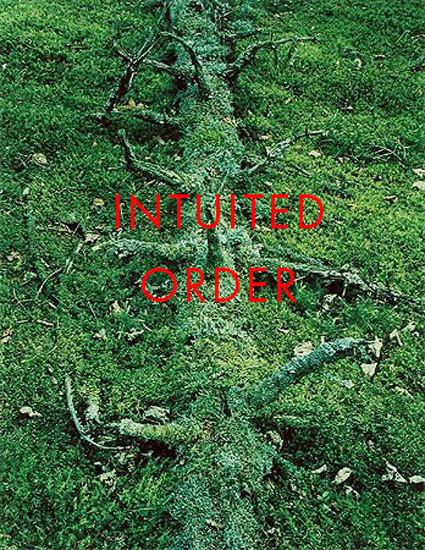

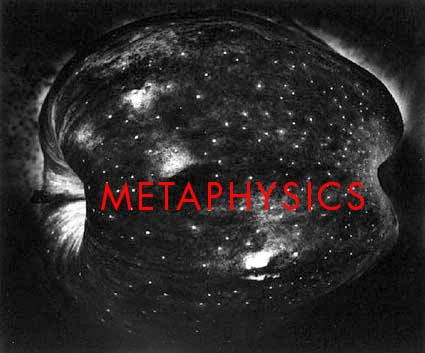

Decades ago, my friend Jeff Schewe asked me, “We both know how to do a lot of things to our images but how do you decide what to do to your images?” My response surprised him, “Talk with them.” Let me expand on that for you, as I did for him so many years ago.

We often deepen our relationship with other people by having a conversation with them. We can do the same with images. Even though they don’t speak, we can speak for them. There are many ways to do this.

Write

Before I go into more detail, let me offer you a crucial piece of advice. Make sure you write this stuff down as you go. You won’t be able to remember everything you come up with and the act of writing will allow you to come back to it and pick up where you left off, help you find more insights, forge deeper connections, and increase the chances that you’ll act on it. All of these benefits happen more strongly when you write by hand but that’s slower and not as easily retrieved, so more often than not, I use the notes app on my phone, which can be accessed from any of my devices. I recommend you try many ways of taking notes to determine which ways work better for you.

Conversations start with questions. Ask a lot of questions. Then answer them as if you were the image. Write that down.

Ask Questions

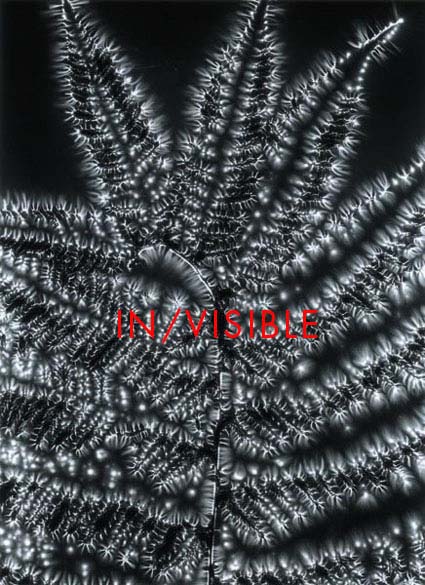

Conversations start with questions. Ask a lot of questions. Ask way more questions than you ever thought to ask. I usually set my goal at 100. Why? The goal of this exercise is to get beyond the obvious and the conventional. Sure, ask those questions too but go well beyond them. Ask the kinds of “crazy” questions kids ask. (What does this image eat?) Pretend you’re someone or something else and ask the questions he/she/they/it might ask. (If you’re the frame … Who put these things in me? And why did they put me here?) Imagine you are the work of art and ask the questions it would ask if it could. (What do I have to do to stay out of that closet?) The skill of asking more questions gets easier if you simply rephrase the same question in different ways to get different perspectives. Change the w word – who, what, when, why, where, how. (What is this about? How does it go about it? Who goes there?) Reverse questions; ask the opposite question. (Why is it lower? Why isn’t it lower? Why isn’t it higher?) Or, add not to any question. (Is it dark? Is it not dark?) Once you have your list of questions scan it for patterns. What kinds of questions did you ask? What did you ask questions about most frequently? What questions stand out as most interesting? Asking questions may be all you need to do to find useful insights. Answers are optional. I recommend hypothesizing what they are and to look for opportunities to answer a single question in more than one way. Remember, write it down. You can revisit your list later and you’ll most likely have a different perspective with different outcomes. You can also repurpose many of the questions in your list to use with other images. This is a skill that gets easier over time. Make asking a lot of questions a habit.

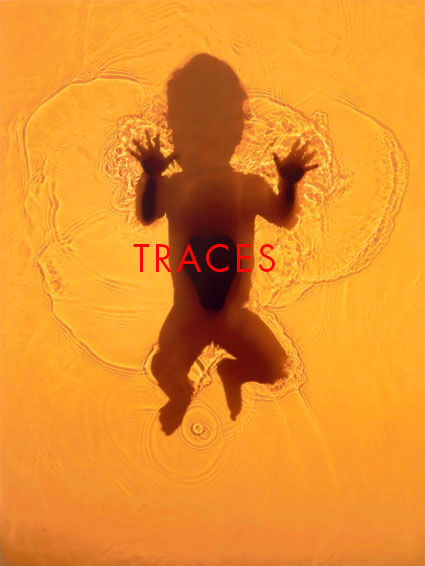

Imagine that you’re the image.

If I were you, what would I do?

If I were you, what would I feel?

If I were you, what would I want?

If I were you, what would I think?

(You can expand these questions by adding “about ___” at the end and filling in the blank.)

Walk a mile in your mind with your images. Just treating your images as if they are sentient creatures will instantly make you feel more connected to them, which will show in your final results, and people who see your images will be drawn closer to them because of that quality.

I recommend you do this more than once at different times. Your moods, influences, and perspectives are constantly shifting, sometimes only a little, sometimes a lot. In fact, practicing these internal conversations is one way of proactively influencing your internal flow. (And yes, we all have a mind-body connection.)

Associate

Let’s talk about you. When you look at an image …

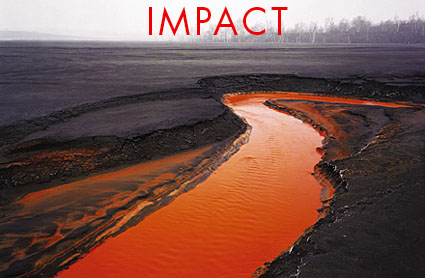

What emotions do you feel? What’s the mix?

How does your body feel when you look at it? Where?

What memories does it bring up? What’s the connection?

What other images do you think are related to it? Why?

What other things does it remind you of?

What single words and phrases would you use to describe it?

Make a list of nouns. What is it of?

Make a list of verbs. What is it doing?

Make a list of adjectives. What qualities do the things and actions possess?

In these kinds of … call them exercises or studies or research sessions … it’s supremely important not to judge or censor yourself. This will stunt the growth of this process, your growth. Write it all down. Nothing is too ridiculous. In fact, if you don’t let a good dose of that irrational stuff out you won’t find as much magic. For the moment, stop making sense. Make sensitivity. Let your inner child out to play with wild abandon. You can clean up your room later.

Ask why five times.

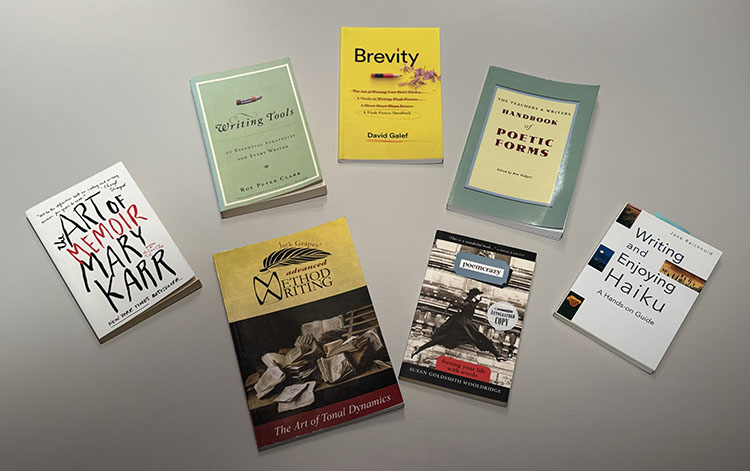

Read More