.

.

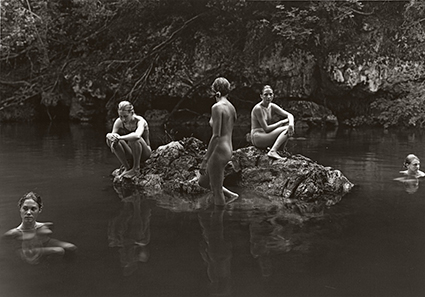

Jock Sturges

View 12 Great Photographs by Jock Sturges.

Jock Sturges is a fine art photographer based in San Francisco, California. Best known for his nudes and extended portraits of families in Northern California counter-culture communities and on European naturist beaches, his large format images borrow significantly from classical periods in both photography and nineteenth and early twentieth century painting. Represented by 16 galleries in six countries, Sturges’ work is also to be found in the collection of many of the world’s museums including The Museum of Modern Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, The Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris and The Frankfurt Museum of Modern Art in Germany. His most recent book “Jock Sturge” (Scalo, 1996) was published in conjunction with a major exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in Frankfurt. Other titles to his name also include: “The Last Day of Summer”(Aperture, 1992), “Radiant Identities” (Aperture, 1994), and “Evolutions of Grace” (GAKKEN, 1994).

Sturges travels to photograph, lecture and teach throughout the world but is reliably to be found working on the beaches of France almost any late summer afternoon. In addition to this, he has been working on a distinctly different body of work in the West of Ireland for the last five years. Publication of this work with Scalo is envisioned in late 1998.

Jock Sturges My work is all about relationship and people whom I’ve known for a really long time. I’m fond of saying that 99 percent of my time as a photographer is not spent taking pictures; it’s spent doing the social work that makes the pictures possible — spending time with people, knowing who they are, helping them with different aspects of their lives, eating together, knowing them. And that makes the pictures possible. In some cases, I’m photographing people with whom I have been working for over 25 years. So, if anything happens in my technique, there’s a kind of endurance or persistence of effort, that results in a picture taking system that allows for a fairly perfected result. Anything that would tend to seduce people away from the notion that an effort, over time, is really what matters in photography, is something I’m suspicious of, or reluctant about. Efforts over time, for me, are the common denominator of all the great bodies of work in photography. Photography reflects the knowledge of the photographer, and that wasn’t achieved quickly or superficially, that was achieved by a huge investment of time and interest. Photography, good photography, is about that.

I mean, face it, what we need to see, what we want to see, in photography is passion. Take the camera away from a photographer and would they still be doing this thing? Would Edward Weston still have been with all those women? Absolutely, he would have been. Would Ansel Adams still have been up in the Sierras every chance he got? Absolutely, he was in love with those mountains. Would Dorothea Lange still have been the monumentally compassionate soul that she was? She certainly would have been. And that persists. That’s what photography is about. For me. That’s what makes it the magnificent art it can sometimes be.

Photographers seem to have this notion, so often, that their photography and they themselves, as “artists”, are more important than who the people in their pictures are. Hello? The people are what it’s all about. We don’t exist without that person there, and our photographs are just the most superficial, fleeting, minuscule percentage of how wonderful they are, on a continuing basis. We just capture a tiny little slice of that. When we’re lucky I start to be truly interested in a body of work of an individual when I have 10 or 15 or 20 years with them. Then I feel like I start to know some things that are true about that person. Because there are things that don’t change, and there are things that do change, and the combination of the two, the balance of the two is what teaches and reveals to you what character is. What resides in a good, long series of photographs is identity. And that’s fascinating! That’s a subject for art for you. Not just another body. Precisely because of this I don’t take on very many new people to photograph anymore – very rarely – because I’m so invested in who I’m shooting already that I feel I’m very often not doing enough, with some individuals, just because there’s never enough time. The things that I learn about the people that I photograph … There are two sisters that I photograph. I’ve been shooting them for some years. And I’ve always marveled at how close they were, even though they’re several years apart. These children literally got their periods on the same day even though they’re two and a half years apart in age. And I discovered this summer, in speaking with the younger of the two, that the older sister was informed, when she was seven, that she’d been born as a twin but that her twin sister had died at birth. She’d been told this when she was seven, had been very traumatized by it, had literally started having nightmares, and had stopped growing until her younger sister caught up with her. And they have since ascended through life, from that moment on, as twins. It’s really fascinating stuff. And so when I photograph them together, there’s this bond between them that I’d never understood, but now I understand much better. What extraodinary luck I have in life to bear witness to, to know, such things. So my photography is all about crafting long-term relationships and working with people I’ve known forever. I’m, in a lot of cases, now, photographing people who are the children of people I started photographing when they were infants, and I feel like I know something profound about who these children are, because I know where they come from so well. And so, as I photograph a mother with her new baby, the experience is as close to religion as I’ll ever get. It’s a sacral experience for me, and it’s just something I adore doing.

John Paul Caponigro How do you feel that is communicated to the viewer? The qualitative not simply the quantitative is communicated. How? And then, what?

JS Let me come at answering that from a slightly different direction. I photograph some people with whom I don’t have relationships. There’s one family of three very beautiful sisters, again, in France, that I’ve shot for years because they’re part of a large social group that I work in, and they’re very beautiful, and so, logically, they get themselves photographed. But they’re kind of superficial, they’re not all that nice, and I’ve never really enjoyed taking pictures of them, even though they’re very pretty. And I’ve never made a good picture of them. There’s no relationship there. And yet, they’re so beautiful that I kind of think, “How can I not get a picture of these girls that’s good?” But I never do. I’d like to. I hate wasting film. It took me years to realize that the deeper the relationship I had with people, the better my photographs got. It’s a simple: A therefore B. Know what you’re photographing. I don’t care what it is. If you can inform your work with some passion, if there’s something about the world, not photography but the world, that you love, then the work that results is necessarily good. It will work, because it’s about something real. But when it’s about photography itself, when it’s a circular thing that’s self-referential, that’s of no interest to me at all. Photography about photography is of no interest. Who cares? It’s like painting about brush strokes. Once again, who cares?

JPC I think about Sally Mann’s or Emmett Gowin’s family work. I bring up the work up because I’m wondering if a sense of family portraiture shares a kinship with your work.

JS Very much. Family portraiture is very important to me. A lot of photographs I take, I take with the knowledge that as I’m making them, if they’re not going to be successful pictures for me, that they’re at least made for the family in question. There’s not a family that I photograph that I don’t do very conventional, piano top type pictures for in the course of everything else that I do. One of the fun things that happens in such instances is that you release expectations when you’re making a photograph with an errand like that. You say, “OK, this is going to be for them, I’m going to make a really nice picture of them all together that they’re really going to like.” And sometimes, because the expectations are released, you come through to really wonderful work. Because you’re not trying so hard, perhaps. There’s a bit of Zen in that, isn’t there?

But, really, the first thing I care about is that everybody I photograph gets a copy of their pictures. Perhaps the most single most important transactions in my work is that the people I photograph own their photographs. And they don’t sign any releases for me. They own their work in a really profound way. If I want to use a picture, I get in touch with them and I explain, this is the use that I want to make, and I get permission for that use. And if I want to use the same picture again a week later, I get back in touch, I explain the new context, and I get another release. I often have giant phone bills, but … When you’re photographing young people, by definition they’re going to change, and you can’t be guilty of making any assumptions as to what those changes might be. So I’m always back in touch with them. And it’s fun to be in touch with summer friends in the middle of winter.

JPC Sure. And it hasn’t been hard to keep track of them?

JS No. I feel like if I don’t keep track of people, I don’t deserve to use their pictures. That much respect is the least that I owe them. On a few occasions, I’ve had people get away from me and it’s taken me some time to find them, and that’s kind of scary. So I have to stay on top of things.

JPC The 8×10 format seems a curious choice. You must have your reasons.

JS The 8×10 is an interesting device I try to be as seamless with it as possible, of course, but by the same token the ponderous large format has several really dramatic advantages when you’re photographing people. One is that the image is upside-down, and therefore viewable as an abstraction. Another has to do with the fact that the level of respect that people perceive they’re being paid with a camera of that size is dramatic. People really respond to the compliment of such an imposing piece of gear, they feel like they’re being taken seriously. And along with that goes the fact that I am not behind the camera when I make the picture, I have direct eye contact. There’s not a machine between us. I get my face very close to the lens axis, and I’m watching intensely. So there’s a wonderful physical immediacy of being right there next to them. The advantage of seeing the image as an abstraction, the compliment people feel they’re receiving, and that direct visual access to the emotions of the moment, that’s the mix that makes the large format camera a uniquely valuable tool for me.

JPC It would also seem that if someone’s taking a big camera a little more seriously, it would bring a certain quality to the poses they exhibit and the interaction. For better or for worse, the looming presence would seem to color the interaction.

JS There’s something else that happens that’s fun. It’s funny, sometimes, too, because it can go too far. I don’t pose people at all. I don’t say, “Stand like this, do this, do that.” I spend a lot of time with people, and every once in a while I’ll see something that works for me and I’ll say, “Don’t move!” Usually my best pictures come when people think we’re done. I say, “OK, we’re finished. I’m done.” I always have film holders left over, and inevitably, that’s when people relax. and do the most unexpected and lovely things. Then I’ll say, “Don’t move, stay just like that, hold still, don’t move your hands.” And that’s my good picture. It’s what’s natural and what comes from the people that’s real. But what happens over time is that a lot of the people whom I enjoy photographing a lot, that I’ve been shooting for years, come to understand that there’s a certain kind of almost balletic elegance that I have a great tendency to like in photographs and they start doing this stuff on purpose. They sort of figure out what it takes to push my button. And so I turn around and they’re doing this long, stretched- out, elongated beautiful thing, and of course I make the photograph. They’ve, in a funny way, made me take that picture. They know that that’s what Jock likes. So that can go too far, sometimes. That can get to be a little bit too self conscious, on occasion. But very often it is actually quite beautiful, how people present themselves.

JPC Are there ways success has modified or influenced the way that you’re currently working, on an artistic level?

JS No. Success hasn’t modified it so much. It’s made it easier for me to work, of course.. I mean, I have a complete set of gear in Europe now, so I don’t have to truck back and forth with it, and a house there. So, I’m set up to work very easily now.

If there’s anything that’s changed how I’m working, though, it’sbeen the thing that happened with the government. I’m far more paranoid than I used to be. And I resent a recession of innocence that’s taken place in my work now. I mean, I was pretty naive in 1990, when the feds came here, and was working with this strange notion that there was nothing evil, sinful or ugly about the body (regrettable or obscene). (That it just was.) I took it totally for granted that Homo Sapiens was beautiful, and that there was nothing that we did that was inherently not lovely. Shame’s a learned response, very often an imposed response. And I think that if there’s a sub agenda to my work, I hope very much that it militates against shame. When people instruct others in shame, they end up getting the opposite result of what they expect. Look at cultures in which the visual depiction of the human figure is even limited beyond nudes, where you can’t show people’s ankles or necks. The greater the extent to which this is true, that visual depictions of the human body are censored, the greater percentage of per capita crimes against women and children in those social systems. The two things go hand-in-hand.

What happens is that when a child or woman is aggressed by somebody who invades their physical self in some way, they’ll either tell or not tell. It’s as simple as that. Systems that have instructed them in shame, to a great degree, are systems in which they are much less likely to tell. The systems that are the most open have, in fact, the lowest statistical incidence of child abuse, because child abusers are caught very early, because kids tell. So the irony is, the people that are militating against my work are militating for a result that will be the opposite of what they expect or pretend to desire. There is, for me, quite a profound irony there.

JPC Controversy certainly hasn’t hurt your success.

JS That’s the irony, these people are so good for book sales. I don’t want that to happen. That throws the critical regard of my work out of balance. I regret that more than I can say

JPC You want the dialog to be on an entirely different level.

JS Absolutely. If my work has merit, fine. And if it doesn’t, then I deserve whatever critical lumps should be dished out, based on the merit of the work, not based on its controversial nature. I hadn’t sought the attention the government paid me. If I’d been given any choice in the matter, I would certainly not have wanted it, and I wasn’t seeking to exploit it. It was just there, and there was nothing I could do but deal with it, fight for my life. And I won but I lost something as well. What’s been stolen from me permanently is, in fact, that objective regard for my work, because now and forevermore, there will always be the asterisks. Which I hate. I won’t ever get that back. That’s been taken from me permanently.

My work is, in fact, neutral. In fact, its very neutrality is one of the things that worries me about it sometimes. There’s sometimes not a lot of emotive passion in the work. Because I shoot long shutter speeds, people are necessarily very still, and the work is very, very plain and…. neutral. That neutrality isn’t sexual by nature. My subjects are just there. So if you read sexuality into my pictures, beyond what’s inherent to a human being, then the work is acting as a Rorschach, and you’re evincing sexual immaturity or sexual malaise in your own life. I have to tell you, I am sometimes deeply suspicious of the sexual mental health of some of the peoplewho point their wavering fingers at the morality, the art, of others. How is it that they are so interested …?

JPC Pure projection?

JS It’s very much projection. It’s amazing how much projection it is. Some of these people, I cannot believe what they see, when they’re looking at my pictures, or other people’s photographs.

JPC It seems impossible to take all sexual dimension out of photographs of human beings. One wonders at what point along the spectrum you address it.

JS It’s a natural part of being human, it’s just there, it’s built into us.

JPC When you, a man, looking largely at women, and by and large, but not exclusively, young women, the notion of sexuality has to be addressed in some way. I’m wondering, what stance do you take towards that, you personally?

JS Well, they are beautiful. Their bodies are lovely. When they’re children, they’re children. They’re beautiful, but not in a way that invites aggression, or sexual interaction – at all. They’re just what they are. And that’s part of the problem, a lot of people seem to be incapable of dividing out simple admiration from a sexual urge.

I’ve never accepted that there is any point along the trajectory that our lives describe from birth until death, that is not beautiful, that is somehow or other inherently obscene or to be hidden. Hiding is bad for us. Hiding makes people perversely interested in the hidden, and ashamed when the hidden is broached.

JPC We talk about photographing a relationship or an emotion, you can’t really touch those things, you can only see their interactions with the external world …

JS Ah! You just hit on something very important for me, which is, including the intangible in a photograph, grounding a photograph in the intangible, something you can’t touch, or see. Let’s put it this way. Every photograph is a record of the relationship that existed between the photographer and the person photographed. If that relationship is superficial and fleeting, let’s say, for example, a fashion photograph, where the relationship consists mostly of money and surface, then the pictures are somehow not very nourishing. In fact, most fashion photographs ever made are now fish wrap, at best. They haven’t endured, they don’t endure in our minds, because there’s little or no relationship depicted. But the great photographs in photography, the ones that we really love, are so often the ones where the relationships depicted are the deepest.

JPC It’s a profound mystery, that that can linger in an object, far after the event has passed, the creator has passed, the subject has passed.

JS As you say, that intangible is residual, it stays forever, it’s there. The basis on which that person there is in the picture endures, and if they’re there as the other half, the grateful recipient of a gesture of respect, then that has the chance to endure. And I think that’s a wonderful thing. I mean, it’s once again celebratory, not just of that person but of the fact that I was able to make the picture, that I was trusted to. Because that’s the great richness in my life, that I know these people and that they care to have me photograph them.